COMETS, METEORS, AND ASTEROIDS: 2. Comets: The Fiery Snowballs

Comet Hyakutake in 1996.

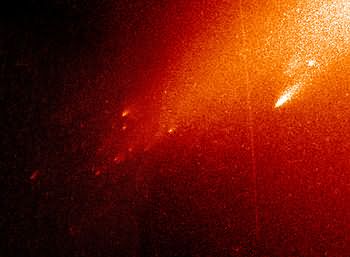

Comet LINEAR.

Few things are quite as exciting as a really bright comet. It may be seen for weeks, even during the day. Like a rocket flame, its tail may stretch halfway across the sky.

But such a comet may come once a lifetime – if we're lucky. Most, even at their brightest, can be seen only with a telescope. The few that can be seen with human eyes alone are usually just faint smudges or hazy streaks in the night sky.<

Comets are among the most mysterious objects in the solar system. They appear from the darkest depths of the Sun's kingdom. They hurtle by the inner planets, corner around the Sun, and for a short time can be seen from Earth. Then they are gone, lost again in the blackness of space.

The Lonely Journey of a Comet

A comet has only a small solid part, called a NUCLEUS, which is usually no more than a few miles across. The nucleus is sometimes said to be like a dirty snowball. It's a chunk of ice and frozen gases in which there are bits of rock and dust. Right at the heart of the snowball may be a rocky core.

A comet, like a planet, goes around the Sun. But a comet's orbit is long and stretched out, different from that of a planet, which is much more circular. It carries the comet quite close to the Sun at one end, and far away at the other.

For many years, a comet will travel on the part of its orbit that lies well away from the Sun. It may journey for hundreds or thousands of years in the outer solar system. During this time, it gets very little warmth from the Sun and remains just a small ball of ice and rock in space. Because it gives off no light of its own, it can't be seen, even through big telescopes, from Earth.

|

| Path of a comet around the Sun |

At last, its path begins to carry it towards the inner solar system again. It passes, in turn, the orbits of Pluto, and of the giant planets: Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, and Jupiter. Gradually, the Sun's heat starts to release some of the gases from the surface of the comet's frozen nucleus. These gases form a fuzzy, glowing ball, called the COMA, around the nucleus.

The coma grows as the comet plunges in towards the Sun. Soon, it can be seen through telescopes on Earth. It may grow until it's more than 100,000 miles (160,000 kilometers) across – about half the distance from the Earth to the Moon.

At the same time, the comet may begin to grow a TAIL. This bright part is made of glowing matter that has been blown out of the coma by the SOLAR WIND – a stream of particles that flows outwards from the Sun. The tail may stretch for millions of miles. Because it's blown by the solar wind, it always points away from the Sun as the comet moves around its orbit.

Comets may have a gas tail – one that's narrow, straight, and pointed exactly away from the Sun. Or, they may have a dust tail – one that's wider and more curved. Many comets have both a gas and a dust tail, along with such markings as streaks, spirals, and rays. Some have no tail at all, just a fuzzy, round coma.

Long and Short Orbits

The biggest difference among comets is in the way they move around the Sun. First, there are LONG-PERIOD COMETS. These travel around huge, stretched-out orbits that carry them much farther from the Sun than any planet. Long-period comets may take thousands of years just to make one trip around the Sun.

Then, there are SHORT-PERIOD COMETS. These have smaller orbits that extend only as far as the outer planets. Short-period comets are divided into two main groups. Those belonging to the NEPTUNE FAMILY (also called Halley-type or intermediate-type comets) make their trips around the Sun in less than 200 years but more than 20 years. They may travel out as far as the orbit of Neptune. Comets in the JUPITER FAMILY, on the other hand, only go out at most, as far as the planet Jupiter and complete a circuit of the Sun in less than 20 years.

Both long-period comets and members of the Neptune family are thought to have come from the same place. Scientists believe there is a huge cloud of dark, frozen comets, called the OORT CLOUD, that encircles the Sun at a great distance. It is probably 50,000 times farther from the Sun than the Earth is and may contain as many as 100 billion comets.

Once in a while, the gravity of a distant star may change the path of a comet in the Oort Cloud and make it plunge in towards the Sun. The comet will still take a very long time to go around its new orbit. Now, though, we'll be able to see it as it comes close to the Sun. It will be a long-period comet.

If the comet happens to pass close to a large planet, it may have its orbit changed again. Instead of a long-period comet, it may join the Neptune family. Then its new path always lies much closer to the Sun. Both long-period comets and Neptune-family comets, though, probably start out in the Oort Cloud.

The case of Jupiter-family comets is different. These objects move in much smaller orbits, having been forced into them by the powerful tug of Jupiter's gravity. Comets in the Jupiter family haven't come from the Oort Cloud. Almost certainly, they have come from another big swarm of frozen objects that lies beyond the orbit of Pluto but much closer to the Sun than the Oort Cloud. This second great collection of icy bodies in the solar system is known as the Kuiper Belt.

The brightest and best known of the short-period comets is Halley's Comet. Halley's is a member of the Neptune family. At its farthest, it is more than 3 billion miles away and much too dim to be seen. Every 76 years, though, it swings close by the Sun. As it speeds around the Sun, it gives us a wonderful view of its brilliant coma and its gleaming, 100-million-mile-long tail.

Halley's Comet last paid us a visit in 1986. On this occasion, it was greeted by several spacecraft that had been sent to study it at close range. For the first time, we caught sight of the small, mysterious heart of a comet – the nucleus.

At its closest, Halley's Comet comes to within 50 million miles (80 million kilometers) of the Sun, which is well within the Earth's orbit. Most comets stay farther away from the Sun. A few, however, come even closer.

Some comets, called SUN-GRAZERS, may crash straight into the Sun, or get so close that they burn up. Once in a while, a sun-grazer will hold together as it speeds around the Sun. Then the Sun's strong force of gravity may hurl it onto a new path that carries it out of the solar system altogether.

The Life and Death of a Comet

A comet has quite a short life compared to that of most objects in space. Each time it comes close to the Sun, its nucleus shrinks a little more. The supply of ice and dust needed to make the glowing coma and tail grows less and less and finally runs out.

A long-period comet may last for millions of years. A short-period one, though, may wear out after just a few thousand years.

What happens to a comet as it starts to get old? If it's like Encke's Comet, with a rocky core in the middle of its nucleus, it may just gradually fade away. Encke's Comet has the smallest orbit of any comet. It hurtles around the Sun once every 3.3 years. Encke's has no tail and only a very small coma. It seems to have lost most of the dusty, icy mixture needed to make a tail and is fast becoming just a dark, wandering boulder.

If a comet is like Biela's Comet, though, it may break up in a much more spectacular way. Biela's Comet was discovered in 1832. Like Encke's Comet, it was a member of the Jupiter family. It traveled around the Sun once every 6.7 years. On its return in 1839, it was lost in the Sun's glare and couldn't be seen from Earth. When it came back again in 1846, however, scientists were able to study it closely. They were amazed at what they saw. Biela's Comet had split into two pieces! When the comet was next seen, in 1852, the pieces had moved 1½ million miles apart.

Biela's Comet, it seems, was nothing more than a crumbly mixture of ice and dust. It had no rocky center at all. On its approach to the Sun in 1839, it must have become so heated that its nucleus simply broke apart.

That breakup, though, was not quite the end of Biela's Comet. It's true that the comet, itself, had gone forever. After 1852, it was never seen again. But old Biela had a ghost, and, like those of many other comets, it still comes back to haunt us each year.