Gunpowder Plot

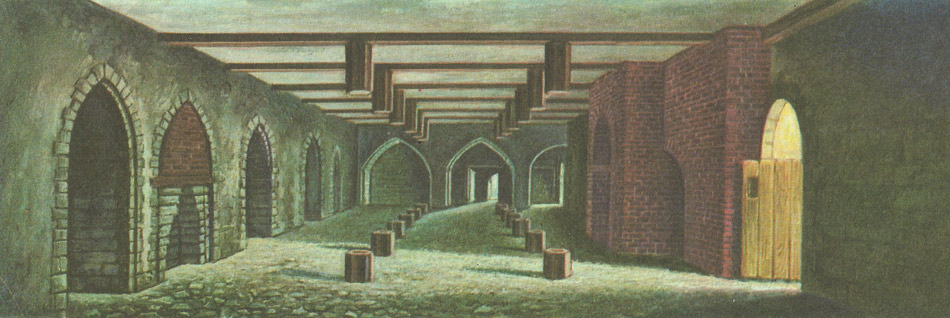

The cellar underneath Parliament where Guido Fawkes was discovered waiting to set fire to 1� tons of gunpowder when Parliament was assembled.

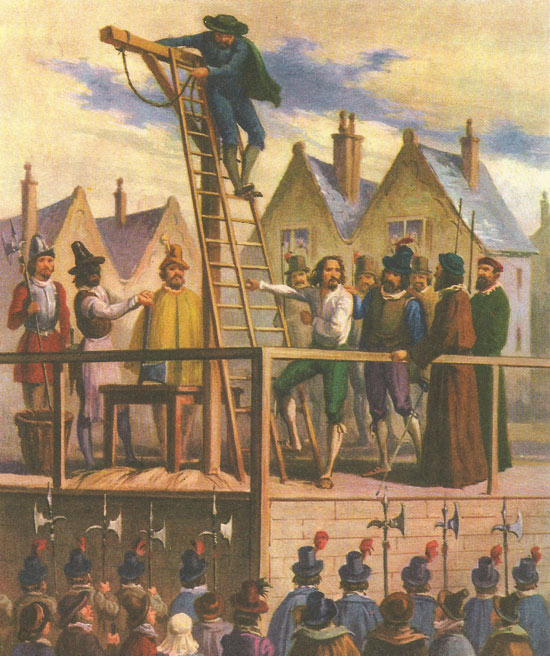

The execution of Guido Fawkes. Weak from torture, he could hardly climb the ladder.

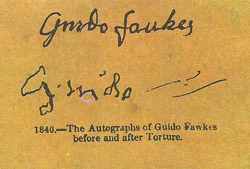

The key to the cellar of the house rented by Thomas Percy.

The Gunpowder Plot has become one of the most famous events in British history. It is strange that this should be so, as it was not really of great importance. Yet every year on 5th November all over the country 'guys' are burned and fireworks let off to celebrate the wonderful escape of King James and his parliament from the devilish 'Gunpowder treason and plot' of 1605.

The plight of Roman Catholics in Britain

What could have persuaded a band of well-to-do English gentleman to conspire to blow up the King and parliament? To answer this we must look at the position of Roman Catholics in Britain at that time. In 1605 about 70 years had passed since the Reformation had come to England and the Church of England had been established in place of the Church of Rome. Many people bitterly resented this change and refused to acknowledge a church of which the Pope was not the head. For these people life during those years had been very hard. They had been regarded by their fellow-countrymen with both suspicion and hatred, and this hostility had been greatly increased by the plots against the life of Queen Elizabeth, by the secret activities of the Jesuits, and finally by the attempt of the King of Spain to conquer England and restore the Roman Catholic faith.

Many harsh laws were passed against the Roman Catholics, or Papists as they were called. For attending Mass they could be sent to prison. For failing to attend a Church of England they could be fined £20 a month. If they tried to convert anyone to their faith it was high treason. These laws were so harsh that they were not always enforced, but they could nevertheless be put into effect whenever the King was so minded.

James I of England

James I came to the throne of England in 1603. He succeeded Queen Elizabeth, who had been one of the most successful and beloved of English sovereigns. It is never easy to step into the shoes of a person such as this – people will always make unfavorable comparisons and hark back to the 'good old days'. Even if James had been wise, humble, and patient king, he would probably have run into trouble. James, although clever, was neither patient nor humble and has been aptly nicknamed 'the wisest fool in Christendom'.

The Roman Catholics had great hopes that James would do something to help them – after all, he was the son of Mary Queen of Scots, the last Roman Catholic sovereign in Britain.

At the beginning of his reign James seemed to be friendly and held out hopes that the penal laws would be abolished. Then he suddenly changed his mind. Perhaps he was irritated by the way in which some Papists looked on him as a Papist at heart. Whatever the reason, in 1604 James suddenly gave orders that the penal laws were to be strictly enforced.

A plot is hatched

To have their hopes dashed in this way caused tremendous disappointment among Roman Catholics, and some of them were prepared to go to desperate lengths. Foremost among these was a Warwickshire country gentleman called Robert Catesby. He was a man of great charm and courage and had tremendous powers of persuasion. He was also a passionate supporter of his faith – so much so that he had once tried to persuade the King of Spain to make another attempt to conquer England.

It was probably Catesby who first thought of the great Gunpowder Plot. This had three main stages. In the first place, the King together with his eldest son, Prince Henry, and both houses of parliament were to blown up and destroyed. Secondly, there was to be a rebellion of Roman Catholic gentlemen in the Midlands. Finally, in the ensuing chaos Roman Catholics were to seize control of the country, and one of the King's younger children, Prince Charles or Princess Elizabeth, was to be put on the throne.

Today is seems incredible that anyone should have believed that such a plot could possibly succeed. But Catesby believed in it passionately, and so persuasive was he in his arguments that he succeeded in getting a number of people to join him.

The conspirators

The first people won over by Catesby were Thomas Winter, John Wright, and Thomas Percy. These men were close friends who had known each other for a long time. The only outsider in the early stages was Guido Fawkes, a Yorkshireman and a soldier of dauntless courage, who was serving in the Spanish army at that time.

In May 1604 the conspirators met for the first time in a house behind St. Clement's Church. There they took and oath of secrecy and worked out the details of the plot. Percy was to rent a house next to the parliament house. From here a tunnel would be dug to extend underneath parliament house and then charged with gunpowder. This work was entrusted to Guido Fawkes.

At first things went well, and the house was rented without difficulty. Then a number of delays arose, mainly owing to parliament going into recess. In March 1605 the conspirators had a stroke of luck: they managed to rent another house which had cellars actually stretching underneath parliament; no more mining was necessary. In the cellar were placed 20 barrels of powder (about 1½ tons), and on top of them a number of iron bars to make the explosion more effective. Parliament was due to reassemble on November 5th.

The plot betrayed

Although the conspirators were not idle during the months of waiting, the delay proved great strain on their nerves, Some of them began to lose their enthusiasm, appalled at the thought that in the explosion Roman Catholics as well as Protestants would be killed. In particular, Francis Tresham could not bear the thought of having a hand in the murder of his brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. So on the October 26th he sent him an anonymous letter warning him not to attend parliament as a dreadful blow was about to strike it.

Monteagle at once took the letter to the King's chief minister, Lord Salisbury. Salisbury guessed that the letter referred to gunpowder. He also remembered the cellar which had been rented by Thomas Percy, but for some reason he took no immediate action, and it was not until November 3rd that the King was informed.

During this time Monteagle made sure that news of the discovery of the plot reached the conspirators. However, although they had plenty of time to flee abroad, they ignored the warning and determined to carry on with their plot.

The end

So it was that on the night of November 4th the cellar was searched and Guido Fawkes found at his post. All the other conspirators then fled to Warwickshire, pinning their hopes on the uprising that had been organized there. But this petered out before it began. At Holbeach House in Staffordshire the conspirators made a last desperate stand against the government's men, and many of them, including Catsby and Percy, were killed.

|

Fawkes was tortured to extract from him the names of his accomplices, but he kept silent until he knew that they had been taken. On 27 January 1606 eight of the conspirators were tried at Westminster Hall. They were convicted and arrangements were made for a spectacular public execution. On 30 January, four of the conspirators were executed in St Paul's churchyard. The following day in Old Palace Yard, Westminster, the others followed, last of all being the man whose name the plot is now associated.

Was there really a Gunpowder Plot?

There are a number of strange and mysterious things about the Gunpowder Plot, and some people believe that the whole thing was a put-up job, engineered by the government, in order to discredit the Roman Catholics. Lord Salisbury was their bitter enemy: it is certain that he knew of the plot several days before the arrest of Guido Fawkes; it is quite possible that he had guessed at it before that. But whether, as some people agree, he used government agents to prompt the whole thing is very doubtful and is not credited by most historians. It is not possible here to go into all the details, but some of the suspicious circumstances can be mentioned: