Attila and the Huns

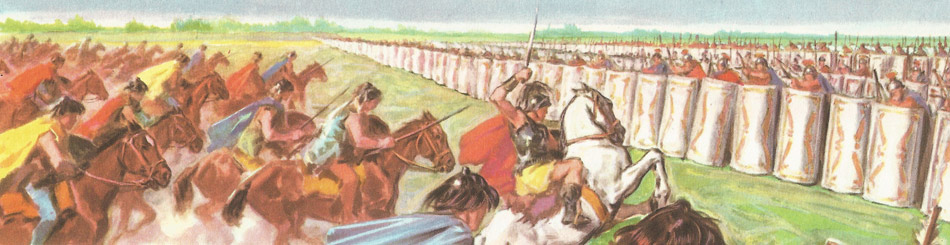

At the battle of Châlons, the cavalry of the Huns charged in vain against the ranks of the Romans.

Attila, King of the Huns, known as 'The scourge of God'.

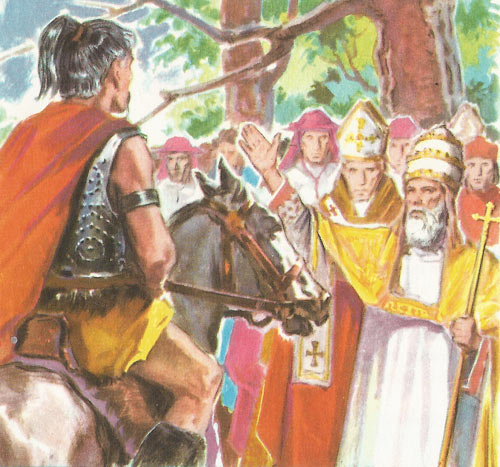

When in AD 452 it seemed certain that Rome would be captured by the Huns, a delegation headed by Pope Leo 1 came out to meet Attila at the Mincio River. It is not known what happened at this meeting. All that is certain is that Attila decided to turn back. For many years it was believed that he was overawed by the Pope. Leo was certainly a remarkable and persuasive man, and maybe he reminded Attila how the last king to capture Rome, Alaric the Goth, had died immediately afterwards. But although Attila spared Rome, he died in the following year.

For many years the Roman Empire had been under threat from the German races (Franks, Burgundians, Goths and others) who sought to settle in their provinces. An agreement was eventually reached, whereby the Danube was regarded as the boundary between the two peoples. But in AD 375 thousands of Germans poured across the river and began to settle in the Roman Empire. The reason for this invasion was not savagery or greed, but fear. A new and fearful menace had appeared in eastern Europe in the form of the Huns.

These people originally came from Asia. A writer of that period wrote that they were so monstrously ugly and misshapen that one might take them for two-legged beasts. In stature they were small, they had a sallow complexion and their heads 'were shapeless lumps with pin-holes rather than eyes'. Their smell was appalling. No wonder that people of that time thought they were the offspring of sorceresses and evil spirits.

It seems they were untouched by any form of civilization. They had no towns or villages, but were always on the move. The men were permanently on horseback: there they ate, slept, conferred together and fought. The women and children followed in wagons. For food they drank the blood of their horses or ate a kind of yoghurt made from rancid mare's milk. They did not undertake any form of agriculture, and the art of weaving was unknown to them. For clothing they relied on the skins of goats and rats. The terror the struck into others was phenomenal. This was partly due to their looks - already hideously ugly, they were make even more repulsive by a great scar on their cheeks. This had been caused by a gash from a sword when they were babies; the idea behind this savage custom was that it made them free from fear. Certainly they fought like demons: they moved at great speed, were quite fearless and had enormous powers of endurance.

First invasions

The Hun people arrived in Europe at the time when the Roman Empire was slowly dying. Gradually they spread over the whole continent. They were most concentrated, perhaps, in the country which today is known as Hungary, but over all eastern Europe – from the Alps to the Urals – there were small groups of these fierce wagon-folk. At first they were too spread out and independent to be a serious threat to the Roman Empire, but then there arose a king who by his power and ferocity made all the tribes of the Huns obey him.

Attila

Attila succeeded his uncle Rua as king of the Huns in AD 434. For a time he ruled jointly with his brother, Bleda, but in 444 he had him put to death and for the next nine years he was one of the most powerful and terrifying rulers there has ever been.

Although he had such great power, Attila was a man of simple tastes. He preferred a rough and simple life, and despised luxury and soft living. Thus his 'palace' was never more than a wooden shack and while his guests might drink out of silver goblets, he himself always had a wooden cup.

Invasion of Roman Empire

At the time the Roman Empire had been divided into two parts – the Western Empire based on Rome and the Eastern Empire based on Constantinople. In 441 the latter was invaded by Attila. The Emperor Theodosius was a weak man and was soon forced to ask for peace and to agree to pay an annual tribute. Nine years later he was succeeded by Marcian who refused to continue this, but by that time Attila's attention was fixed on the Roman Empire of the West. He was preparing to invade it with a huge army consisting not only of Huns but also of men from German races which he had conquered - Franks, Vandals and Burgundians.

Princess Honoria

The real reason for Attila's invasion of the Western Roman Empire was his lust for power, but the one he proclaimed was a curious one, namely that he was coming to the rescue of the Roman princess, Honoria. Some years ago, this young woman had been caught having a secret love affair with a palace official. Her mother was very angry and banished her to Constantinople where she was kept under strict confinement by her grandfather, the Emperor Theodosius. However, somehow she managed to send a message to Attila. In this she besought him to be her husband and come to her rescue. How much Attila really cared about the fate of the unfortunate Honoria is doubtful, but he sent a number of threatening messages both to Rome and to Constantinople on the subject, and finally made it an excuse for invading the Western Empire.

Battle of Châlons

In 451 Attila's army advanced into France – burning, destroying and pillaging as it went. At first it swept all before it, but near to Orleans it was brought to a halt. Here it was opposed by the great Roman general, Aetius, who has been called 'The last of the Romans'. He had made an alliance with his old enemy, Theodoric, king of the Visigoths; it was these people who had invaded the Empire 50 years ago and sacked Rome in AD 410. Since then there had been constant fighting, but now they forgot their old quarrels and joined forces against the Huns.

Together they forced Attila to withdraw from Orleans, and then followed him to the Catalanian Plain (near Châlons). The battle which followed was believed by many to be one of the most bloody that had ever been fought in Europe; both sides suffered enormous losses. The principal casualty was King Theodoric, he was succeeded as king by his son Thorismund who felt it necessary to return home at once in order to make sure that he had no rivals. But for this, the army of the Huns might have been destroyed utterly, as already it had been heavily defeated. At is was, Attila was allowed to withdraw, and eventually he reached his own country and safety.

Invasion of Italy

In the following year (452) Attila returned. This time he advanced into Italy, and the destruction and havoc which he wrought in the north of that country earned him the description of 'The scourge of God' (flagellum Dei). This year Actius had been taken by surprise and Attila encountered practically no resistance.

The way to Rome seemed clear, and it appeared almost certain that once again this great city would fall into the hands of savages. But then Fate intervened. For some reason Attila decided to turn back. It may be that he was persuaded by Pope Leo I or it may be that there were more practical reasons. For in Italy at that time there was not only famine but also plague; his army was both hungry and disease-ridden. Also there was a danger that his line of retreat might be cut off; the Eastern Roman Emperor was already moving against him. Altogether there were strong reasons why Attila should withdraw.

This was to be Attila's last campaign. In the following year he took as his wife a beautiful woman called Ildico or Hilda. As was the custom he had a huge marriage feast, and he ate and drank so much that he burst a blood vessel. His nose started to bleed and nothing could stop it; and so not on the battlefield but in a orgy of feasting, died the man who had caused Europe more fear and suffering than any other human being.

After the death of Attila the empire of the Hun fell to pieces. Attila's sons quarrelled among themselves and in a fearful battle over 30,000 Huns were killed. Of the remainder some settled in Europe, but most of them returned to their original lands in south Russia.