From Augustus to Nero

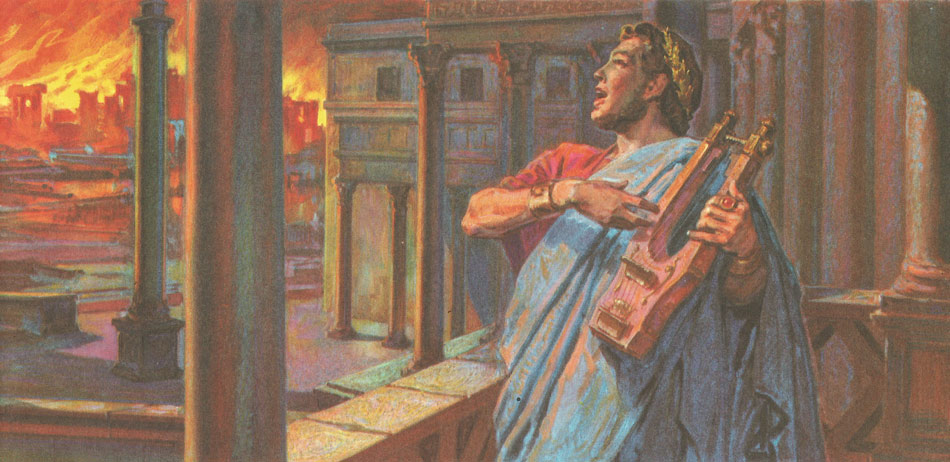

During the great fire which destroyed much of Rome in the autumn of AD 64, Nero was said to have declaimed poetry to the accompaniment of a lyre.

Lands whose conquest was begun by Claudius.

Remains of the aqueduct of Claudius, in the countryside near Rome.

When the Emperor Augustus felt that he was on the point of death, he is said to have recited the Greek actors' epilogue, asking for applause if he had played his part well. Augustus certainly deserved applause. During the 44 years of his rule he had given the Roman Empire peace and prosperity and a stable form of government that preserved the best features of the Republic. He had also given justice and security to Italy and the provinces as well as to Rome. In AD 14 he died. It was now for his successors to continue his great work.

A worthy successor to Augustus

|

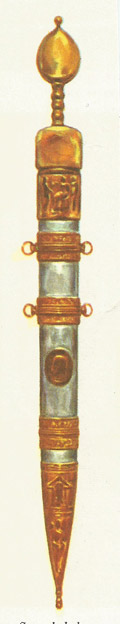

| Sword belonging to Tiberius (British Museum)

|

Augustus was succeeded by his 55-year-old stepson Tiberius, an able commander and governor, who continued his work. As Emperor, Tiberius tried for as long as he could to make the Senate a real partner in the administration. In the provinces he took pains to ensure good government, choosing his procurators with great care. And, like Augustus, he sought to maintain peace within the Empire, and to stabilise the frontiers by diplomacy rather than by fighting. But Tiberius, a lonely and diffident man, suffered a good deal from jealousy within his family. Indeed, when is popular nephew and adopted son Germanicus, and later his own son Drusus, both died in suspicious circumstances, Tiberius was widely (though quite unjustly) suspected of having them poisoned.

Weary of misunderstandings, the ageing Emperor retired to the island of Capri, leaving affairs at Rome in the charge of his trusted friend Sejanus, Prefect of the Praetorian Guard. Sejanus, however, was treacherously plotting for his own advancement; through his influence many innocent men were condemned to death for 'treason'. At last Tiberius realized the truth, and Sejanus himself was condemned to death. Tiberius was not popular in Rome, partly because he did not waste money on lavish public spectacles. Nevertheless, he was very generous in cases of real public need. He died in AD 37.

|

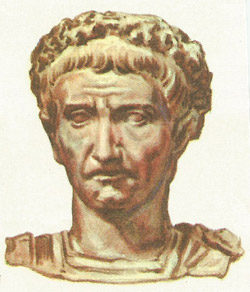

| Marble bust of Tiberius (Naples: National Museum)

|

A mad Emperor

The next Emperor was Tiberius' great-nephew Gaius. As a child he had been in Germany when his father Germanicus was Roman commander there. The soldiers nick-named him Caligula ('Little Boot') from the little pair of army boots his mother had made him.

Gaius was at first extremely popular, and for several months it seemed as though the 'golden age' of Augustus had returned. Then he had a serious illness which affected his brain. Recklessly he squandered the fortune left him by Tiberius' careful administration. Soon he was demanding to be worshipped as a god; he ordered prominent senators to commit suicide; he imposed all kinds of new taxes; he upset Tiberius' sensible frontier arrangements. In less than four years he managed to unite everyone against him. After two unsuccessful conspiracies, he was killed in AD 41 by one of his own Praetorian Guards in a corridor of his palace. Some of the fantastic stories told about this mad Emperor (for instance, that he made his horse consul) are doubtless exaggerated; but it was fortunate for Rome that he did not live longer.

|

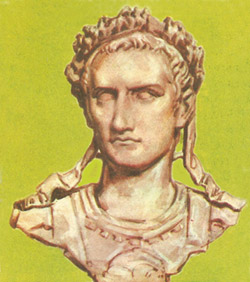

| Marble bust of the Emperor Gaius (Caligula)

|

A scholar turned statesman

The Senate thereupon debated whether to restore the Republic; but the Praetorian Guard seized Gaius' uncle Claudius and made him Emperor. Claudius was an elderly scholar with great respect for ancient Roman institutions. He proved capable and conscientious. His provincial administration was generally good. He tried, with some success, to collaborate with the Senate; he broadened its composition by introducing nobles from Gaul and other provinces.

Claudius gave Rome an imperial Civil Service, using freedmen from his own household. Some of these gained considerable power and wealth; this was not liked at Rome.

|

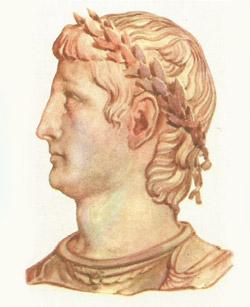

| Head of the Emperor Claudius (from a cameo)

|

Britain becomes a province

Ever since Julius Caesar's visits, the Romans had intended to add Britain to the Empire. Claudius decided the time had come; he wanted to strike the native religion of Druidism at its heart, for the Romans distrusted the power and prestige of the Druids, and he needed the lead of Devon for water-pipes.

So four legions crossed the Channel in AD 43, and gained quick victories. South-east Britain was declared a province. Within four years this was extended as far as the Fosse Way; but it was another 40 years before all Britain south of the Scottish Highlands was subdued by Agricola.

Mauretania (Morocco) was also conquered, and was made into two provinces.

Imposing public works

Claudius was also responsible for expensive but useful public works. He built a magnificent aqueduct, several arches of which still survive. to improve the water supply to Rome. After a threatened shortage of corn early in his reign, he built a great new harbour and granaries beside the old port of Ostia. He also drained part of the Fucine Lake.

A cruel Emperor

In his later years Claudius fell under the evil influence of his fourth wife Agrippina. Thanks to her, Claudius was poisoned in AD 54, and was succeeded, not by his son Britannicus but by his sixteen-year-old stepson Nero.

At first, while Nero was too young to rule, the Empire was well governed by Seneca, his tutor, and Burrus, Prefect of the Praetorian Guard. These men ended the worst feature of Claudius' administration - trials held behind closed doors in the Emperor's palace. But soon Nero wanted to take charge himself. There was a strain of brutality and cruelty in his character; this became very clear when, to get his own way, he arranged for his own mother to be murdered.

Nero was convinced that he was a great singer, poet, and actor. He made a personal appearance on the stage (this shocked many Romans) and also competed in the great athletic and artistic contests of Greece. Needless to say, he was always awarded first prize!

When the great fire of AD 64 destroyed much of Rome, it was rumored that Nero himself had started it; so he decided to persecute the Christians as scapegoats. This and many other pieces of cruelty turned all classes in Rome against him. Nero's final mistake was to order the death of a successful general. Important sections of the army revolted, whereupon Nero fled and committed suicide.