Giotto (1266–1337)

The Miracle of the Fountain (detail). Assisi, Church of St Francis.

The Prayer to the Birds (detail). Assisi, Church of St Francis.

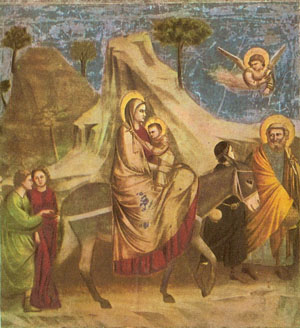

The Flight into Egypt. Padua, Arena Chapel.

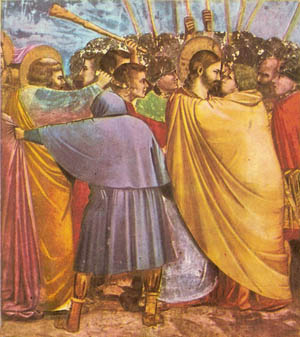

The Kiss of Judas. Padua, Arena Chapel.

One day in about the year 1302 Pope Benedict XI sent a messenger to the city of Florence in central Italy. The messenger's task was to discover the best painters in the city, which was famous for its artists, and bring back samples of their work for the Pope to see, for the Pope had decided to decorate his palace with beautiful paintings.

The messenger was directed to the workshop of Giotto, where he requested a drawing to show his master. Giotto took a brush, dipped it in red paint, and with one sweep of his arm drew a perfect circle, saying it would be enough to show the Pope the painter's quality. He was right, because the Pope at once engaged him to paint frescoes in his palace.

How a shepherd became a painter

This story is told by the Italian historian Vasari, who wrote the lives of many greater painters. Little is known of Giotto's youth, but scholars believe he was born in 1266 at Vespignano, a little town in the hilly country a few miles north of Florence. His father was a peasant farmer, who probably owned his own land. Giotto went out to work as a shepherd when he was very young. Vasari relates how Giotto used to take his sheep to a pasture to graze, and sit drawing pictures on a smooth rock with a piece of burnt wood. One day a stranger walking in the hills noticed the boy making a sketch of one of the lambs in his flock. He drew so well that the stranger, who was a painter himself called Cimabue, asked him if he would like to learning drawing and painting in Florence.

Giotto's father agreed to allow his son to start as an apprentice in the workshop of Cimabue. The poet Dante, who met Giotto after he became famous, wrote that Cimabue was the best painter of his time until Giotto surpassed him. Giotto learned how to paint frescoes, in water colors on wet plaster, to adorn the interiors of churches and how to make mosaics – pictures composed of tiny pieces of colored stone and glass stuck in cement or plaster. Unfortunately frescoes fade when exposed to light for many years, and mosaics become chipped and damaged; when later artists repair them much of the original work is lost. But enough of Giotto's work has survived to show what a great painter he was.

His earliest works are some of the frescoes in the Church of St Francis, at Assisi, which tell the story of the saint who befriended animals. The top two illustrations here show two of the frescoes; they represent a remarkable advance over earlier, Byzantine art.

Painting before Giotto

The Byzantine style of art was used in early Christian churches in the dark, violent years after the fall of Rome and the barbarian invasions. It was called Byzantine after Byzantium (or Constantinople), the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, which survived until 1453, when it was finally captured by the Turks. Byzantine art, in which eastern and western religious ideas meet, appears grand was seen on a large scale, as in a cathedral, but is stiff, inhuman, and unchanging. Pictures were made in mosaic or painted in fresco on wooden panels in two dimensions only, length and breadth; they had no depth, and so the figures had no roundness or solidity, any more than figures cut out of paper. The artist was not trying to make his saints and prophets look like real people, but to show them as symbolic figures, always the same, so that they could be recognized at once. This was important in an age when few people could read or write. The Byzantine artist used forms and symbols that were full of religious meaning, but had nothing to do with everyday life and experience; the Church laid down rules which the artist had to keep in his choice of subject, method of work, and even the colors he might use.

This kind of painting lasted for 600 years. Then Giotto broke through its long tradition with an entirely new idea of what painting could be. He was the first painter who saw life – people and things – in the round. His figures had weight and volume as well as shape and color, and his houses and trees are just as real and convincing as his people and the things they are doing. Giotto broke all the rules of Byzantine art and changed the whole direction of painting. His art was concerned with human beings who move, breathe, and speak, hope and fear, feel joy and sorrow, here on this Earth, in a landscape that he had known from boyhood.

Giotto's works

The finest and best preserved of Giotto's works can be seen today in the Arena Chapel at Padua. The chapel was built in 1305 on the site of a Roman amphitheatre. Giotto's great dramatic power and his sense of design are shown there in the 38 scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary. The lower two illustrations here show the beauty and energy of his compositions.

Painters in the fourteenth century had to rely on observation, not on scientific study, because their knowledge of the human body and its structure. They had only the beginnings of an understanding of perspective, and they had not yet dealt at all with the problem of light. But Giotto developed painting as far as was possible without this knowledge. In his mastery of expressive lines, his arrangement of groups and harmonious colors, in the direct and vital gestures of his figures, his work was unlike any painting of the previous 600 years, and it was a starting point for new explorations in art.

Giotto painted in many Italian cities, though little of his original work remains. He made a mosaic of Christ saving St Peter from the waves, in St Peter's in Rome, where it can still be seen, much altered and restored. He decorated five chapels in the church of Santa Croce in Florence which were whitewashed after his death and only restored 150 years ago. The crowning honor of his career was his appointment as architect of the new cathedral in Florence. He planned the west front and the bell tower, or campanile, and they were built according to his designs. The lower courses and sculpture of the campanile were begun in his lifetime, though he did not live long enough to see the superb tower soaring against the Florentine sky. The carefully studied buildings in many of Giotto's frescoes show his interest in, and knowledge of, architecture.

Giotto the man

Many writers, including the poet Petrarch and the story-teller Boccaccio, pay tribute to Giotto's genius and give the impression of a witty and good-natured man, friendly and efficient, and fine craftsman as well as artist. These writers do not tell us much about his family life, except that he married young and had six children, three sons and three daughters. His success brought him enough money to buy land to add to the property at Vespignano which his father had left him. He died in January 1337, and on his tomb in the cathedral in Florence another painter from the same city wrote his epigraph, a hundred years after his death: "I an he by whose undertaking the dead of painting was restored to life."