obelisk

Figure 1. Erection of an obelisk. 1. The base of the obelisk was placed on the edge of the pedestal on which it was going to stand. The obelisk was made so that one side of the base could be fitted into a slot cut in the pedestal. This prevented the obelisk from slipping while it was actually going up. 2. While the obelisk was raised by ropes and jacks, a heap of material (usually bricks) was pushed underneath it to support it and keep it steady. 3. Finally the heap of bricks grew high enough to allow the obelisk to stand upright on its pedestal. .

Figure 2. 'Cleopatra's Needle' by the River Thames in London.

|

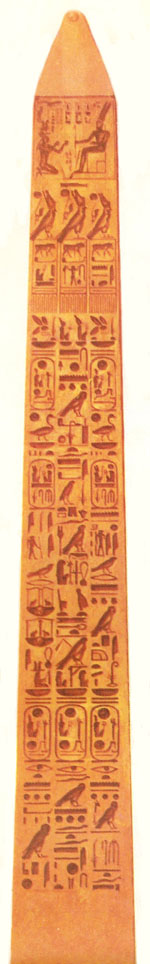

| Figure 3. Obelisk at Luxor.

|

In height, as a rule, they are about ten times the diameter of the base. The point was usually sheathed in a bright precious metal, silver or gold, but of these valuable metals were stolen long ago. Because of the layer of metal the columns reflected the sunlight brilliantly and they could be seen from a great distance.

Obelisks were carved out of a stone called syenite (so-called because it was extracted from the caves of Syene, today named Aswan), which was a form of reddish-colored granite. Sometimes a dark gray basalt was used.

The dimensions varied: the tallest known obelisk remains unfinished in a cave at Aswan (127 feet high) and the smallest is less than 6½ feet high. They were not merely decorative but stood in front of the temples and were usually dedicated to the sun gods. On many obelisks there are inscriptions in hieroglyphics (the Egyptian picture-writing) saying to which gods they were dedicated.

How obelisks were built

The huge unfinished obelisk at a cave at Aswan helps to show us how such monuments were made. First of all the Egyptians insisted that the stone to be used should have no defects, such as cracks or blemishes. Next the rock was cleaned with powerful jets of water. Then the surface of the rock was planed until it was smooth and flat. To do this, especially hard stones from the desert valleys of Egypt were used. These stones often weighed 9 or 10 pounds each. After planing, the contours of the obelisk were marked out on the ground and a deep ditch was dug out around them. Then the slaves went down to work in ditches. They scraped the obelisk with round stones and then set to work to polish the sides.

The fourth face of the obelisk was torn from the seam of rock with enormous wooden wedges which were driven into previously prepared holes at regular intervals. The wedges were soaked with water, and as they expanded the rock split.

At this stage a group of slaves (about 5,000 strong) worked with ropes and jacks to raise the obelisk from the ditch and to heave it on to planks resting upon wheels. The obelisk was transported by this method to the Nile; it was then loaded on to a long barge to be taken to its destination.

How they were erected

On arrival, the next task was to pull the obelisk upright. As some monuments weighed 500 tons, this was obviously quite a problem. Figure 1 shows the stages by which the Egyptians probably did it.

Where the most famous obelisks are found

Although obelisks were typical Egyptian monuments, they can be seen today in many other countries. Some obelisks were taken from Egypt by foreign conquerors; others fell into ruin because of earthquakes or were worn away by wind and weather.

It is amazing to think that out of thirteen obelisks at Karnak, only three are now left. Among these are the famous ones erected by Tutmos I. Several obelisks were also erected in another city of ancient Egypt called Heliopolis, 'The City of the Sun.' The oldest known obelisk of its kind stands on the outskirts of this city (now a suburb of Cairo): it was erected in about 1950 BC. The obelisk at Luxor is famous for its fine hieroglyphics. It was erected by Ramses II in the 13th century BC, and stood in front of the Temple of Luxor together with an identical one which is now in Paris. It is about 80 feet tall.

When the Romans conquered Egypt in the first century BC they took several obelisks with them back to Rome. There they remained in the main squares until the 16th century AD.

Paris, New York, Istanbul, and London each have an obelisk. The well-known monument beside the Thames and the one in New York's Central Park are twins, popularly called "Cleopatra's Needles." They were constructed in 1500 BC during the reign of Thutmose III, stand nearly 21 meters (70 feet) tall, weigh about 180 tons, and are made of red granite.

The one on the Thames embankment was presented to Britain in 1819 by the Viceroy of Egypt, but it did not reach London until 1878. The cost of transporting it was paid by a private citizen, Erasmus Wilson, and it was nearly lost on the way in a storm in the Bay of Biscay. Sealed up in its base are a newspaper, a copy of Bradshaw's Railway Guide, and some English coins dated 1878. It was scarred by bomb splinters in the Second World War.