Persian history

The growth of the Persian Empire under Cyrus, Cambyses, and Darius.

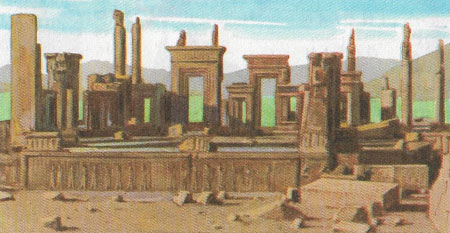

The palace of Darius at Persepolis.

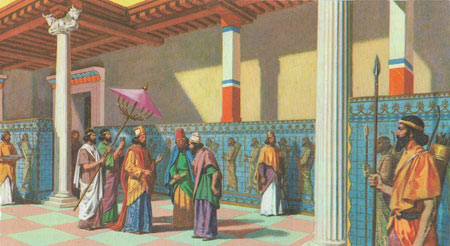

In one of his palaces, King Darius receives Croesus, the King of Lydia, and Nabonidus of Babylonia, both of whom he had defeated and captured in battle.

The tombs of the Persian kings at Nakshi-i-Rustum near Persepolis. On the right is the tomb of Darius the Great.

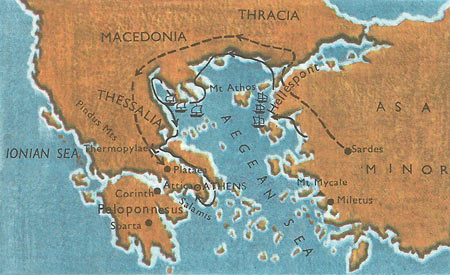

The land and sea routes followed by the Persians in the Second Persian War.

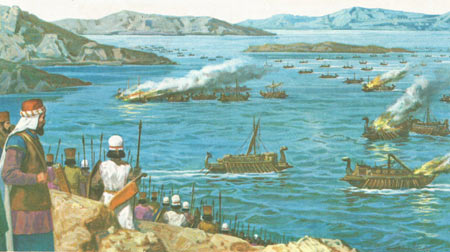

Persian ships burning at the Battle of Salamis.

Persians first settled on the plateau of Iran (that is the present territory of Persia) several thousand years ago. The first evidence of them appears in Assyrian inscription of the 9th century BC. In early times Iran was divided into two parts. In the southwest was Ancient Persia, a country of mountains and deserts, with isolated fertile valleys in which grazing and crop cultivation were possible. To the north of Ancient Persia lay the rival kingdom of the Medes, a country with a large empire which they had conquered from the Assyrians. But the history of Persia as a great nation began in the sixth century BC when Cyrus united the various Persian tribes and defeated the neighboring peoples, thus building a large empire.

Persian history can be divided into two main periods. The first period starts with the age of Cyrus and goes on until the Arab conquest in AD 651; the second begins in the year AD 651 and goes on until the present time. In the second period Persia/Iran has been a Moslem country.

Cyrus the great

About 550 BC Cyrus, the first king of Ancient Persia, captured Astyages, King of Media, and eventually assumed control of the Median Empire. At that time the Persians had two great enemies, the Lydians in the west and the Babylonians to the south. Lydia lay in what today is western Turkey. In 550 BC it stood between the growing Persian Empire and Greece. If Cyrus could capture Lydia, the way lay open for him to conquer Greece. In 546 BC he defeated Lydia's king, Croesus, and Lydia with its Greek colonies came under Persian rule. Croesus was one of the richest kings of the ancient world and his country contained many gold mines. Today we sometimes describe a person as being as 'rich as Croesus'.

Cyrus's dream was to conquer Babylonia, even though people said that Babylon was unconquerable and contained enough food to withstand a siege for 20 years. It was in the year 539 BC that Cyrus marched towards the impenetrable city. One night while the citizens were feasting Cyrus led some of his men a short distance up the river Euphrates. They had a brilliant plan. They broke down the river bank and diverted the river from its route into a nearby depression. The river ceased to flow past this point, and his men were able to creep along the dry river bed into the city and took it completely by surprise. Too late, the ruler Belshazzar saw 'the writing on the wall' which foretold the conquest of his country (Daniel 5: 25-31). The inhabitants were treated leniently and many Jewish slaves in Babylon were allowed to return to Palestine, Cyrus was hailed as 'king of the world, king of Babylon'. He died about 529 BC and was buried in the royal city of Pasargadae.

Cambyses, the son of Cyrus, was coarse and tyrannical, but successful. In the seven years of his reign he added Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Egypt to the Persian Empire. The historians Herodotus tells us that he went mad and killed himself in 522 BC.

|

| The tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae as it stands today.

|

The Empire under Darius

In the following year Darius came to the throne. The Empire was in turmoil after its mishandling by Cambyses, and it took some time to secure support from some of its provinces. Darius set about extending the Persian Empire in all directions. He led and expedition north-westwards across the Danube to the Scythians of southern Russia, and another east to the Indus. In Egypt he cut a canal from the Nile to the Red Sea (not the present Suez Canal) so that his boats might sail from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.

Darius now decided that it was time to add Europe to his list of conquests. In 492 BC he marched into Thrace and Macedonia, but his supporting fleet was wrecked off Mount Athos before he could attack Greece itself. Two years later his fleet sailed directly across the southern Aegean to Eretria, which was destroyed, and then on to Marathon. Here 20,000 troops were landed, and Phillipides was sent on his famous 'marathon' run to warn Sparta. The Persian army was defeated and Darius had to postpone his attempt to conquer Greece. In fact he never tried again, dying in 486 BC, before his next expedition could get underway.

Darius had been a just ruler. He helped the Jews to rebuild their Temple in Jerusalem. He built fine roads throughout his Empire, including the royal road from Sardis to Susa, and also began to build the great palaces at Persepolis and Susa.

The decline

Darius was succeeded by Xerxes, who tried to carry on where his father had left off. In 481 BC he gathered together a large army and fleet from all parts of the Empire for a fresh invasion of Greece. He built a bridge of boats to that his army could cross from Asia to Europe. The first bridge was destroyed by a storm; and after the King had (as he supposed) punished the water by having it flogged with 300 lashes and ordering a pair of manacles to be thrown into it, the Persians built a new bridge of boats. Two bridges were made: one, Herodotus tells us, of 360 ships lashed together, the other of 314; they were skilfully anchored to resist wind and currents, planks were laid across them, and brushwood inserted between the planks. Herodotus tells us that he took seven days and nights for the huge army to cross the Hellespont (Dardanelles). In order to avoid the peninsula of Athos, where his father's fleet had been wrecked, he cut a canal about two miles long, near the modern village of Nea Rodo.

Xerxes had collected an enormous army, the largest the Greeks had ever seen. Herodotus tells us that the land army alone numbered 1,700,000 men; but we probably ought to take at least one nought from this figure. Even so, it was formidable, and for once the Greeks presented a united front. But they could not agree on a strategy. They sent a force to Thermopylae, the narrow pass between the mountains and the sea across which any army marching down the coast had to come. But many of its leaders thought this too far north to provide an adequate resistance. The people of Sparta in particular wanted to fall back to the Ishtmus of Corinth, and defend the Peloponnesus only. But the King of the Spartans, Leonidas, realised that they would lose many of their allies if they abandoned northern Greece. So he decided to defend the pass of Thermopylae. For several days wave after wave of Persians came against the Greeks guarding the narrow path. But they made no headway. Then a Greek traitor called Ephialtes went to Xerxes, and offered to show him a path over the mountains by which his troops could take the Greeks from behind. A picked force of Persian troops was sent over the mountain path by night and the Greeks found themselves hopelessly outmanoeuvred. Leonidas had sent away most of his army, but he, together with a small Spartan force of 300 and a few others, held their ground. They fought heroically against the Persians, and inflicted great losses on them; eventually the Spartans retreated to a small hillock and fought until every one of them had been killed.

|

| Bust of Leonidas – the hero of Thermopylae

|

After they had marched through the pass of Thermopylae, the Persians invaded Attica. They laid waste Athens and other cities. But the Athenians had been told by the Delphic oracle to defend their city 'with a wooden wall', and taking the advice of Themistocles they had interpreted this to mean a fleet of ships. During the battle of Salamis the Greek ships were anchored in a narrow strait where seamanship and knowledge of the shoals and the coastline counted far more than numbers. Many of the Greeks wanted to move the fleet back to the Isthmus of Corinth, but Themistocles settled the argument by secretly advising the Persians to block the escape route on the other side of the island. Both fleets prepared for action, and Xerxes took up a position on a hill on the mainland from which he could look across the straits towards the island of Salamis and watch how the battle went. The Greeks had at most 380 ships; the Persians far more. But Greek discipline and seamanship were much better, and most of the Persian ships were put out of action. Xerxes watched the defeat of his fleet from a hill overlooking the sea.

|

| A bust of Themistocles – his 'wooden walls' smashed the Persian fleet.

|

The destruction of his fleet made Xerxes anxious about his lines of communication – tremendously important for the huge army he had brought. So he decided to retreat and leave the renewal of the attack to his general, Mardonius. Mardonius wintered in Thracia and Macedonia, and renewed the attack on Greece itself in the next year. Heartened by their victory at Salamis, the Greek cities put a large force into the field against Mardonius in the spring of 479 BC. Although the Persian army was larger, the difference in numbers was not as great as in the battles of 480 BC. They fought near Plataea in Boeotia, and in a long and hotly contested pitched battle the Greeks were victorious and the Persian invasion was brought to an end. On the same day as the battle of Plataea, by chance, the Persian fleet suffered another defeat; the Greeks took it by surprise at Mycale, near Miletus in Asia Minor, and destroyed it. Xerxes's attempt had been decisively thwarted and Greece was saved. The great Persian empire remained a threat for many years to come. Attacks on the Greek mainland were planned from time to time, but no invasion on the scale of that of 480 BC was mounted again; and although many Greek cities in Asia Minor continued subject to the Persians, Greece herself remained free.

Xerxes spent the rest of his life completing and adding to the great buildings at Persepolis which had been started by his father, Darius. He was murdered in 464 BC. The murder of Xerxes marked the beginning of a rapid decline in Persia; a century of chaos followed, and in 330 BC Alexander the great routed the Persians at the battle of Gaugamela. Codomannus, the last king of Persia, was killed on the road to Bactria as he fled from the battle. The Persian Empire had fallen to its old enemies, the Greeks.