The struggle between Pompey and Caesar

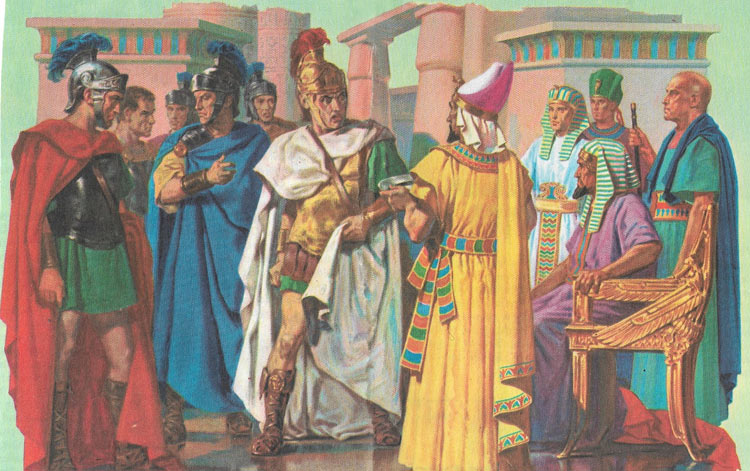

The servants of Ptolemy XIV offer Caesar the severed head of Pompey as a proof of the death of his rival. At this revealing sight Caesar turns away in disgust.

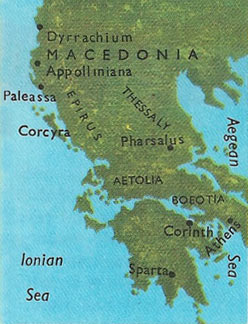

Sites where the final phases of the war between Pompey and Caesar were fought.

The eagle which surmounted the standards of Caesar's legions.

Bust of Julius Caesar.

By the year 60 BC, it was clear that the government of Rome could no longer be conducted on the lines that had been satisfactory before Rome had become the mistress of the world. The old Republic, with its elaborate precautions to prevent one man seizing too much power, would have to be replaced by a system which would allow one man to rule the empire. Three men were rivals for the supreme position in the state: Pompey, the greatest commander of the day; Julius Caesar, whose genius was already recognized; and Crassus, the richest man in Rome. Conscious of the assistance each of them might give the other, these three men formed an alliance (the so-called 'First Triumvirate') for the purpose of ruling the state between them. But this alliance did not last long: Crassus was killed in the Parthian War in 53 BC, and a struggle for power broke out between Pompey and Caesar. For more than a year (from the beginning of 49 to the end of 48 BC) this struggle convulsed the entire Roman world.

Caesar's skilful move

By 51 BC Caesar had become the most distinguished public man in Rome. His conquest of Gaul, completed in the previous year, had established his reputation as the greatest commander of the day. Furthermore, his position at the head of a large, well-trained, and loyal army made him the most powerful man in the state. He prepared to return to Rome to celebrate his triumph and stand for the consulship.

Caesar's reputation naturally aroused Pompey's bitter jealousy. During Caesar's absence in Gaul, Pompey had managed to have himself appointed sole consul, a unique honour which gave him absolute power. He saw that he must maintain his position by eliminating his rival; Caesar could only be made powerless by being deprived of his loyal legions. Without the support of an army he would be completely at the mercy of Pompey, who had a large and well-equipped army at his disposal in Spain.

In order to bring his plan into action, Pompey resorted to a stratagem. By an agreement with the Senate, he revived an ancient law, which required candidates for the consulate to appear in Rome after they had given up their military command. Caesar, however, did not allow himself to be so easily outmaneuvered. He let it be known that he was prepared to disband his army provided that Pompey would do the same with his own army in Spain.

Pompey now had to show his hand. If he rejected Caesar's offer, he would show beyond any doubt that his object was to remove Caesar and to establish himself as the absolute ruler of the Roman Republic.

On 1st January 49 BC the Senate, acting at the instigation of Pompey, rejected Caesar's offer. Julius Caesar could no longer doubt the intention of his rival.

Pompey's flight

In this critical situation Caesar showed the same lightening speed in decision and action that had already won him such distinction as a soldier. When news of the Senate's decision reached him, Caesar ordered his soldiers to cross the Rubicon, a river which marked the boundary between Cisalpine Gaul and Italy, on the night of 10th January 49 BC. By leaving the boundaries of the province which he governed, Caesar was declaring war on the state. It was an irrevocable step, and the phrase 'to cross the Rubicon' is still used of a decisive action which cannot be reversed.

Pompey, caught completely off his guard, had no time to form a plan of action, but left Rome and made for Brindisi. Here he hoped to organise an army and make contact with the troops who were still loyal to him in Spain.

Caesar allowed him no time to do this. On 9th March he reached the port of Brinidi with all his legions. Pompey decided to cross over to Greece, and try there to raise an army. Meanwhile, Caesar took advantage of his position as undisputed master of Italy to return to Rome and have himself appointed dictator on1st April.

Caesar in Spain

Although he had been forced to flee from Italy, Pompey was by no means defeated. He still had enormous forces at his disposal in Spain, and he as now busy raising a large army in the East. He was trying to bring about a carefully devised plan, to attack Caesar simultaneously from Greece and Spain and surround him.

Once more Caesar forestalled his rival in the carrying out of this two-pronged attack. Before Pompey could bring his plan into action, Caesar arrived in Spain and attacked Pompey's legions. Caesar is said to have made the following comment on the situation before he left for Spain: 'I am going to fight an army without a commander; I shall return to fight a commander without an army.' In the first days of August 49 BC Pompey's legions surrendered to Caesar. The war in Spain had hardly lasted 40 days.

The great betrayal

Meanwhile Pompey had received help from all over the East, and had collected an army of 45,000 men and a war fleet of 600 ships, as well as innumerable merchant ships. This fleet gave Pompey complete control over the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. With such an effective guard, it seemed impossible that Caesar's troops would ever be able to cross the Adriatic and attack Pompey in Greece.

But once more Caesar brought the impossible. In the depths of winter, in 5th January 48 BC, at the most unsuitable time for sailing, he succeeded in transporting 15,000 men from Italy to the small harbour of Paleassa, halfway between the island of Corcyra and Apolliniana. The crossing took place at dead of night and was completely unobserved. When news of the crossing reached Pompey, Caesar was already marching against Dyrrachium, the city which Pompey had made his headquarters. Here a battle between the two armies took place during the early days of July. Both sides dug trenches between which the battle was fought.

Caesar came off worse in these manoeuvres, and decided to withdraw into the interior of the country to reorganize his army and join the reinforcements which had followed him by land from Italy. Pompey was now convinced that victory was in his grasp, and he left Dyrrachium in order to pursue Caesar and force him to give battle. On 9th August, near Pharsalus in Thessaly, the decisive battle of the war took place. With his brilliant military instinct, Caesar was able to foresee his rival's every move. Realizing that Pompey was depending largely on his superiority in cavalry, Caesar decided to make the cavalry helpless. About 2,200 infantry were given the task of advancing steadily on the cavalry, aiming mercilessly at the eyes of the horses and their riders. Terrified by his ruthless and unusual attack, the Pompeian cavalry fled. Seeing this, the infantry became demoralised, and the entire army was completely destroyed.

|

| The Roman column, named after Pompey, at Alexandria in Egypt

|

Death of Pompey

After the disaster at Pharsalus, Pompey set out for Egypt. Here he believed that many of his veteran soldiers would come to his aid, and he hoped for help from the king of Egypt, Ptolemy XIV, whose father he had once helped. The young king – he was little more than 13 – was at first advised to refuse to allow Pompey to land. Then it was decided to use treachery. A boat went off to Pompey's ship with the general of the Egyptians troops; Pompey was invited to enter this boat, and as he stepped on to the shore he was murdered. Caesar arrived shortly afterwards. If Ptolemy and his advisors hoped to win Caesar's favour by their treachery, they were disappointed. When the head of Pompey was brought to him on board his ship, he turned away weeping. Pompey had been for many years his son-in-law, and if he had found his old enemy alive he would certainly have spared his life.