Anglo-Saxon settlement

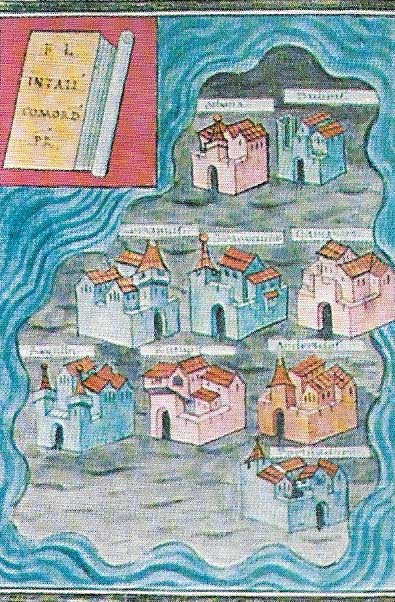

Figure 1. The "Saxon Shore" Forts, shown here in a Roman map, were part of a system built in the 3rd century to protect the south and east coasts of Roman Britain from raids by barbarians. Some of these forts may have been manned by Saxons who stayed after the Roman withdrawal.

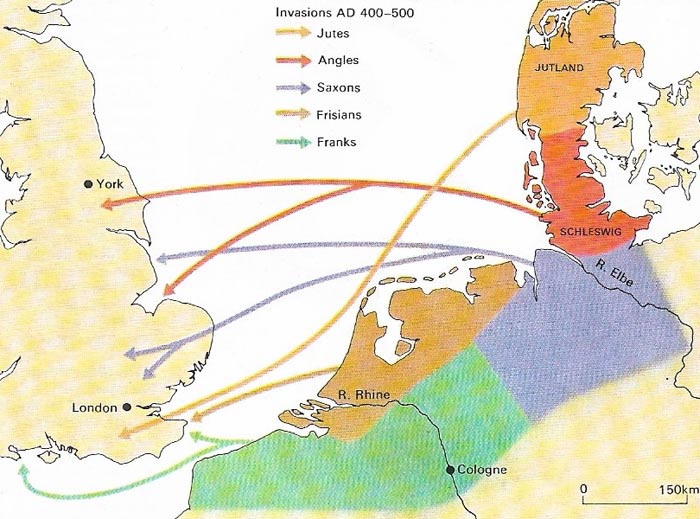

Figure 2. The 5th century invasions came from the far coasts of the North Sea. The Saxons were from Germany between the Elbe and Weser rivers, the Angles from Denmark and the Franks from the Rhineland. Other tribes came from Frisia. They had been driven from their homes by tribes from the east.

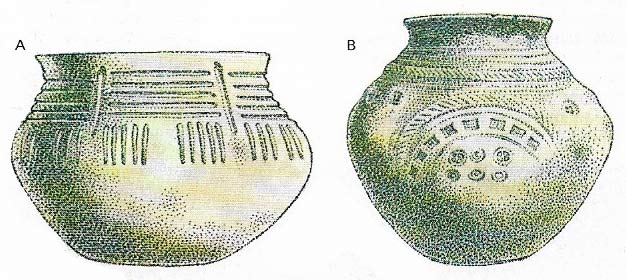

Figure 3. Early Anglo-Saxon pots survive in large numbers because they were used for burial of cremated bodies. They were often clumsy and badly fired, although elaborately decorated. The Continental ancestors of the settlers also used these pots, so they can now aid in tracing the various tribes in Britain. The Continental Angles, made pots with linear grooved patterns (A), while the Saxons preferred bizarre bossed and stamped decoration (B). In England these styles became mixed, suggesting a quick loss of separate tribal identity. With the spread of Christianity, burial rather than cremation in pots became the rule. Use of Romano-British potter's wheel died out by 500.

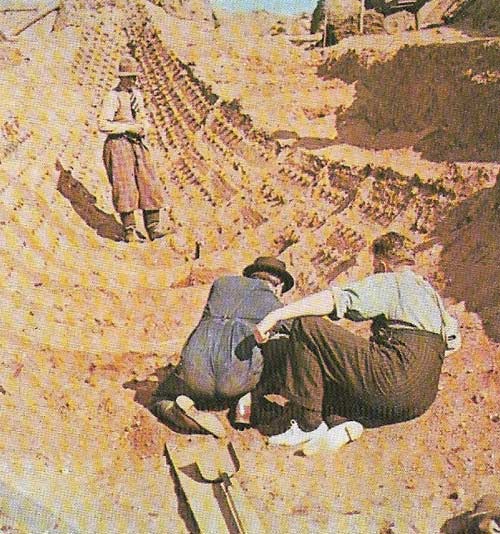

Figure 4. An Anglo-Saxon ship found at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, in 1939, was the cenotaph or memorial of a great king, and contained much glorious jewelry and many domestic utensils. It is not certain which king the ship commemorated, but he may have been Raedwald of East Anglia. It dates from before the final acceptance of Christianity in that kingdom (c. 650). The invaders were sea-faring people. And ships played an important role in their mythology and religion. The Sutton Hoo ship, which was almost 29 meters (89 feet) in length, is the best example of the boats they used. It was primarily a rowing boat, but may have had a sail. It probably had an elaborate carved figurehead on the prow.

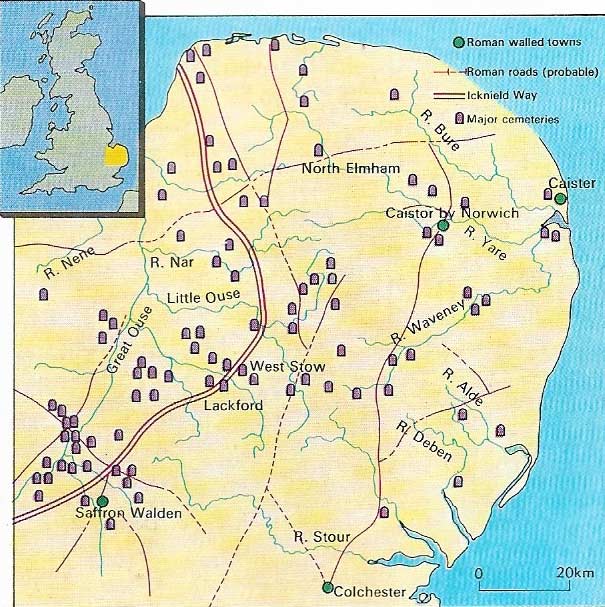

Figure 5. East Anglia was settled earlier and more densely than any other region, being the part of Britain closest to the invaders' homelands. From the pattern of 5th-century burial grounds in England it appears that the immigrants sailed up the rivers and settled along the valleys and Roman roads. Some invaders sailed up the Wash and moved both south and north. Cemeteries at North Elmham in Norfolk and Loveden Hill in Lincoln contain thousands of burials, and show that by the mid-5th century much of the population was already barbarian. The kingdom of East Anglia soon became wealthy as can be seen by the treasures found in the Sutton Hoo ship burial of c. 625.

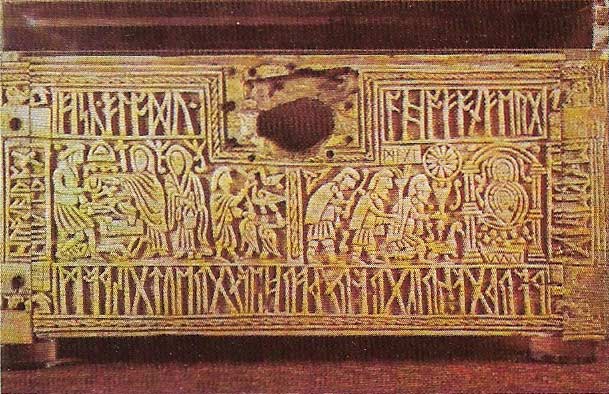

Figure 6. The Franks Casket, a small whalebone box, was made in Northumbria c. 700. Its decorative carvings include pagan and Christian myths, and it's inscriptions are in both Latin script and Germanic runes. This panel shows the Adoration of the Magi and the story of Weland the Smith from Germanic mythology. The Anglo-Saxons often added Christian elements to their existing myths, as can be most clearly seen in the epic poem Beowulf, probably written after 700. But the Church was important in secular affairs by the 7th century, and many kings gave land and wealth to monasteries.

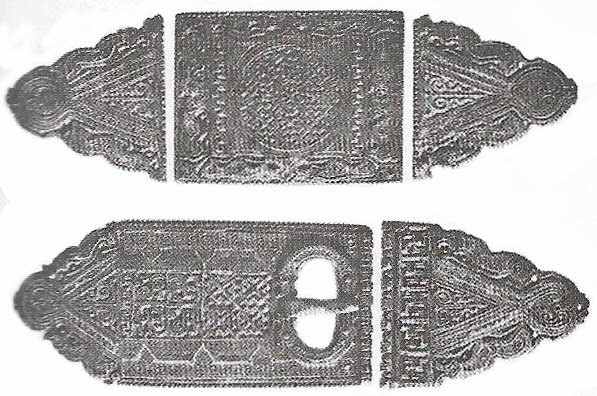

Figure 7. This bronze gilt belt-set was found in a grave in Mucking, Essex. It belongs to a type current on the late Roman army but is in a style found only in England, indicating there was a close relationship between the barbarians and the Roman army.

In the course of the 5th and 6th centuries the once-unified Roman province of Britain was split into a collection of petty kingdoms, barbarian Saxon in the south and east, Celtic in the west and north. The Venerable Bede (673–735), was clear about the origins of the barbarian invaders and the date of their arrival. They came, he said, in about 450 from three tribes, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Modern archeological research has confirmed that the main regions from which distinct groups of settlers came were indeed Angeln, part of Schleswig and southern Denmark, and Lower Saxony, between the Elbe and Weser river mouths (Figure 2). The identity and origins of the Jutes remains more problematic. Peoples not mentioned by Bede, including Frisians and Franks, also played some part. None of these peoples appears to have retained a separate cultural identity for long after their arrival.

|

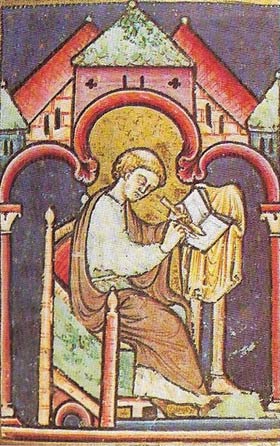

| The Venerable Bede was a monk who wrote the best surviving account of the early Anglo-Saxon period. Working in the early 8th century, he aimed to tell the story of the Church in England. He tried to be more critical of the sources he used (such as earlier chronicles as well as legends and hagiographies) than previous writers and is considered to have been the first English historian. Writing at Jarrow in his native kingdom of Northumbria, he tended to regard Celtic Christianity as heretical, but he admired its great men, especially St. Columba (521–597) who brought Irish Christianity to Scotland, and St. Aidan (d. 651), Bishop of Lindisfarne. |

The earliest Saxon settlements

Contrary to Bede's opinion, there were already Saxons living in Britain before the Roman withdrawal. Sea pirates, known generally as "Saxons", were raiding the eastern and southern coasts of Britain throughout the 4th century (Figure 1). By the late fourth century it was common practice in the Roman army to employ mercenary bands under their own leaders, who fought, often against peoples related to themselves, in return for land and money.

There are large cemeteries in eastern England which contain thousands of cremated burials, many in pots similar to those at equivalent sites of the 4th and 5th centuries on the Continent (Figure 3). Mucking, a village in Essex near Tilbury on the Thames, where occupation began early (Figure 6), is a site of some strategic importance, where Saxons would not have been able to settle so early without a position of some power, whether won by treaty or force.

When the regular Roman army withdrew from Britain in 410 the British leaders had to look after their own defence but continued the practice of employing mercenaries. Gildas, a Celtic monk who lived in the 6th century, wrote in graphic but perhaps exaggerated terms of the result of this policy: the barbarians against their employers and "fire and slaughter spread from sea to sea over the entire island". The story, recounted by Bede, of Hengist and Horsa, mercenaries who rose up against Vortigern who had hired them to protect Kent from the Picts, may have been a significant, although not the only, incident in this rebellion.

The survival of Romano-British society

Gildas was writing within living memory of the events he described, in a period of peace established after a British revival and defeat of the Anglo-Saxons, perhaps under the leadership of Arthur. Frequently the penetration must have been peaceful and gradual. As late as the mid-5th century the native British had time to indulge in religious dispute, and St Germanus had to visit them twice from Gaul to combat the Pelagian heresy (which denied original sin). Despite the general decay of town life, he visited Verulamium (St Albans), a city in eastern Britain, which contained a functioning water system well into the 5th century.

During the invasions, many of the British aristocracy may have emigrated or been killed, yet it is unlikely that all the existing population could have been slaughtered. Enslavement or absorption through marriage with the invaders was more likely. It is significant that the Anglo-Saxon language absorbed very few Celtic words other than names of natural features; but the Anglo-Saxon word for "Briton" also meant "slave". The barbarian invaders of France, by comparison, were not sufficiently numerous to eliminate the language, which became an amalgam of Germanic speech and Latin. But the distribution of place names with a British origin suggests that the bulk of the Saxon settlers arrived and settled in the eastern half of the country. Anglo-Saxon penetration to the west was slow, and the invaders may have lived alongside the Britons, instead of displacing them, as was once thought.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

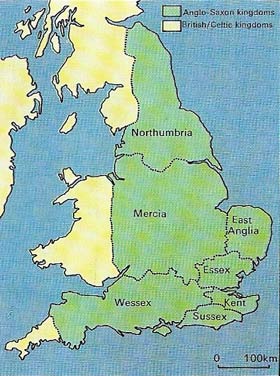

The small warrior bands and groups of migrants, organized by family and clan, evolved gradually into petty kingdoms, of which seven devoted into stable entities. These kingdoms have given the name "Heptarchy" to Anglo-Saxon England from the 6th to 9th century. Frontiers were not constant, kingship was personal rather than hereditary, and the balance of power was constantly changing. The most powerful king at any one time might be known as the "bretwalda", a name meaning perhaps "British leader" or "power wielder". The bretwalda had an informal power over the other kings. Raedwald (died 625), King of East Anglia, who was perhaps commemorated in the great ship burial at Sutton Hoo (Figure 4), may have been such a Bretwalda.

Until the seventh century the Saxons were pagan. Their conversion to Christianity (Figure 6) resulted from two missions, the official Roman one by St Augustine (died 604), who arrived in Kent in 597, and the Celtic monastic one from Ireland, which won most favor in Northumbria. Differences in practice between these two, especially concerning the calculation of the date of Easter, led to dispute, which was resolved for Northumbria at the Synod of Whitby in 664 in favor of the Roman tradition.

|

| St Cuthbert (d. 687) was one of the best-loved Irish or Celtic churchmen of Anglo-Saxon England. He is seen here being presented with a book by King Athelstan. Although he had a Celtic training, he supported decisions of the Synod of Whitby which ended the confusion over the date of Easter. A holy may known for his piety and humility, he was bishop of Lindisfarne. Miracles were said to occur at his tomb, now in Durham cathedral. His history was recorded by the Venerable Bede. |

|

| The kingdoms of the Heptarchy were often in conflict with one another and sometimes sought help from the Celtic kingdoms of Gwynnedd in Wales or Dalriada in Scotland. The center of power altered quickly. |