history of agriculture

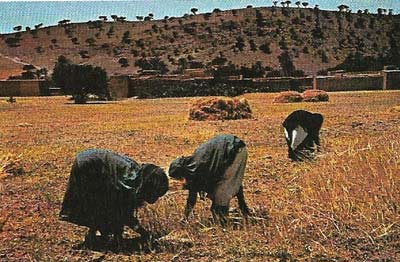

Figure 1. Primitive agriculture involves the whole family in the task of providing enough food for subsistence. The field work is mainly done by women, after the men have completed the heavier work of clearing the land with oxen. While men tend the animals, women plant, harvest, and wage a constant battle against weeds. Work patterns of this sort persist in many peasant communities. The surplus of crop production over the subsistence level is often small; a year of crop failure from drought will mean hunger and possibly even starvation in this inefficient system of agriculture.

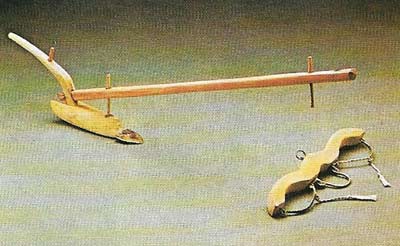

Figure 2. The ard or scratch plow, still is use among peasant cultivators in some parts of the world, does not invert the soil but breaks the surface for sowing. Originally dragged or pushed by men, it was later adapted for pulling by oxen, which doubled the area that could be plowed. Various methods of attachment were devised, usually with a rigid shoulder yoke pegged or strapped in place.

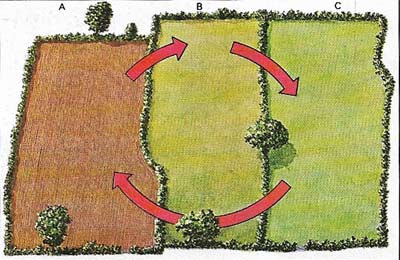

Figure 3. Crop rotation farming, introduced in Europe in the Middle Ages, was based on three fields. One (A) would be left fallow, the second (B) would grow wheat or rye, and the third (C) would be in barley, oats, and peas. Medieval fields were vast, unfenced areas arranged round the village. Each field was divided into a large number of strips and each villager was allocated strips according to his status. As well as working in his own land the villager would also work that owned by the feudal lord of the manor. Despite the principle of division of land, this system had many disadvantages, including the loss of land because of pathways between the strips and the possibility of a badly farmed strip affecting other strips.

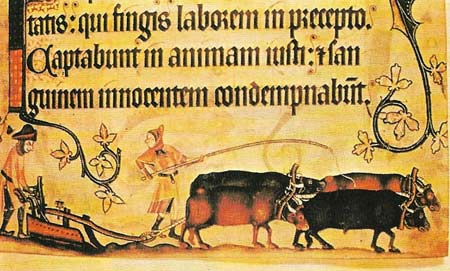

Figure 4. Ox teams provided the basic power units of the farms of the Middle Ages in northern Europe. The sturdy plows used had extended farming to the heavy soil, which had defeated earlier cultivators. Cattle were still bred as work animals but their milk might be made into butter and cheese. The plow ox was fattened for slaughter when seven to nine years old. The working day of the oxen plow team was limited by the need for the animals to graze. The horses that replaced them could work longer hours and also pull the plowfaster.

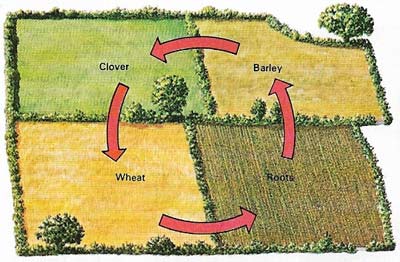

Figure 5. By introducing new crops the Norfolk four-course rotation eliminated the fallow year. Clover and turnips fed more stock and the manure from the stock helped in the growing of improved crops.

Figure 6. Stock breeders of the 18th and 19th centuries considerably improved beef cattle. The new breeds produced the extra meat that was needed to feed the growing population of northern Europe.

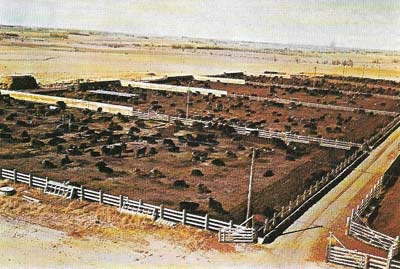

Figure 7. Large numbers of beef cattle are kept throughout the year in open yards such as this US feed lot. Several thousand cattle may be assembled for fattening on a balanced diet of maize, silage, lucerne, grain, and a mineral supplement. With mechanized feeding, labor requirements are small and each animal's growth is rapid. The capital required is large and the owners are more likely to be corporate companies than traditional private formers.

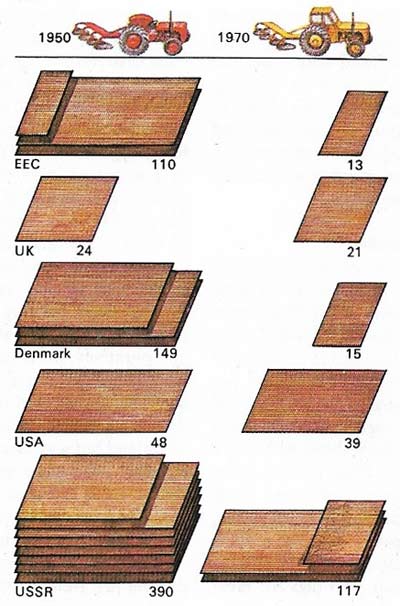

Figure 8. A rapid replacement of man and animal muscle power by machines took place after World War II. This can be illustrated by dividing the area of farmed land by the number of tractors in developed countries to give the number of hectares worked by each tractor. In 1950 the US and the UK were already mechanized, while parts of Europe were using horse-drawn machines and the USSR was recovering from war losses. By 1970 there were proportionately more tractors on the tiny farms of Western Europe, and those on larger holdings in the USA and the USSR had become more powerful and versatile machines.

When Homo sapiens first evolved, he lived in the same way as other animals, by gathering vegetable food – grain, fruits, roots, and nuts – and by killing animals for meat. It was only about 10,000 years ago that man domesticated animals and discovered how to cultivate nutritious plants and harvest them.

Primitive farming methods

About 7000–9000 BC, the invention of the digging stick and a light plow (the ard) Figure 2), made it possible to prepare the soil to grow crops. The basin of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and the valley of the Nile became the centers of great civilizations, founded because there was enough food to supply the non-farming population. Similarly, fanning evolved in northwest India, in north China, in the southwestern parts of the United States and in Central and South America. Various plants were cultivated, such as rice in the East and Maize and gourds in the Americas. Such primitive farming continues to this day in many parts of the world.

|

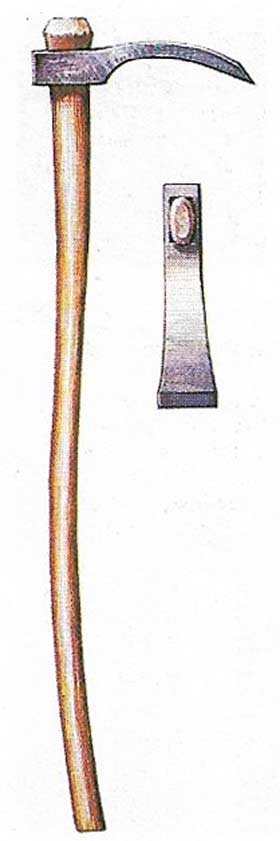

| The mattock or heavy hoe was the basic and sometimes only tool used in early cultivation. It was used to break new ground or shift stones and it served as a hoe while the crop was growing. |

The people of ancient Greece and Rome imported grain from Egypt and Africa, but both also grew some food – grapes, figs, and olives – of their own. The Greeks and the Romans plowed with ards, and possibly used animal-drawn harrows. Sickles were used for harvesting the grain they cultivated (wheat and barley, not oats or rye). Domesticated animals included horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, goats, poultry, and bees. The system of farming was crop and fallow; that is, a crop was grown one year and the land left fallow during the next in order to allow it to recover its fertility.

In northern Europe the forests were cleared from the land chosen for cultivation. First the larger trees were felled, the brush cut, and the whole area burned. High yields (for the times) of rye and oats were sometimes harvested. After a year or two the land was allowed to revert to scrub. This system, known as "slash and burn", is still practiced in parts of Central Africa.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire the Anglo-Saxons conquered England and brought with them a new type of farming that was spreading all over western Europe. This was the open field system (Figure 3). The arable land was divided into three great fields cropped in a rotation of wheat or rye; barley, oats, peas, and beans; and fallow, although plowed three times a year. Sheep grazed meadows after the hay harvest and possibly stubble-fields. The new heavy plough, hauled by two to eight oxen (Figure 5), turned over the long furrows in difficult soil.

The Moors had conquered most of Spain and brought with them new crops — sugar cane, rice, and subtropical fruits – as well as Merino sheep, ancestors of the great flocks now bred in Australia. The silkworm was introduced into Italy and fed on mulberry trees, while rice was grown extensively in the south and also in Piedmont.

New crops, methods, and machines

From America and the Indies new crops and new foodstuffs, the most important of which was the potato, were brought to Europe. Maize was rapidly adopted in Spain, southern France and Italy, as was tobacco. Tomatoes and gourds were important novelties. It was in Europe that the most significant progress was made in farming techniques.

By the fourteenth century farmers in the Low Countries had begun more intensive cultivation of crops on the fallow land, mainly grains, root crops, and fodder plants – clover, lucerne, and rye-grass. The dye crops, madder, woad, and saffron, were also cultivated. As mechanical skill developed, a method of drilling seed by machine instead of broadcasting by hand was invented and this was to be one of the foundations of modern mechanical farming.

The intensive cultivation of fodder crops made it necessary to abandon the open field system and to make fenced enclosures, both to protect the growing crops and to contain the grazing animals. The four-course rotation (Figure 5) replaced the three-course rotation of open fields. This allowed higher productivity and the feeding of more domestic animals, which were also being slowly improved by selective breeding.

It was the opening up of the American plains in the 19th century that provided the real impetus for mechanization. The plains could grow millions of tons of wheat to feed the booming population of industrializing Europe, but local labor was both scarce and expensive. By 1850 a reaping machine was already in use, just before a steam engine was produced to apply power to plowing, harvesting, and threshing.

Scientific farming and increased yields

The work once done by animals is today accomplished by the tractor, while combine harvesters and other complex machines gather the crops. A hectare of wheat in AD 1200 might yield 420–530 liters (12–15 bushels); today 1 hectare (2.5 acres) of wheat in Europe, America, Argentina, Australia, or Canada might yield 3,500–7,000 liters (100–200 bushels). In 1200 the yield of one hectare was enough for four or five people for a year; today, in the advanced countries of the world, a hectare can supply bread sufficient for between 20 and 50 adults for a year as well as seed for the next sowing.

Stock farming has also made unprecedented progress, particularly in the last hundred years. Farm animals have been improved, producing more offspring, meat, eggs, or milk in less time than before.

|

| Modern farming is growing increasingly specialized. The flat, fertile silts of South Lincolnshire, for example, seen here from the air, carry no livestock. This is an area of "cash crops": potatoes, sugar beet, field vegetables, and bulbs, with wheat as a break in the rotation. Some farms are large and make much use of machines. The business side is also well developed with large, private and cooperative investments in crop processing and marketing. |