history of artillery

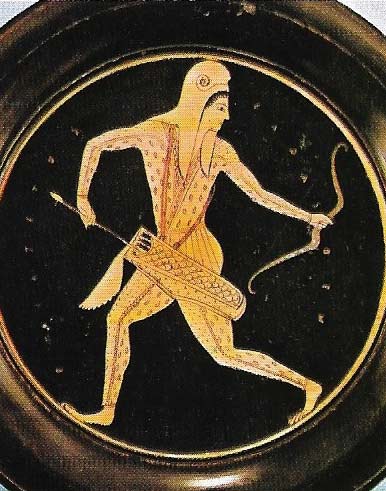

Figure 1. The bow introduced the principle of storing energy for sudden release. It was used in warfare by the ancient Greeks – classical Greek technology could be very competent when there was a slave shortage. Bows and arrows continued to be used in warfare even after the invention of gunpowder because they were cheap, effective, and accurate. The crossbow was developed in the Middle Ages.

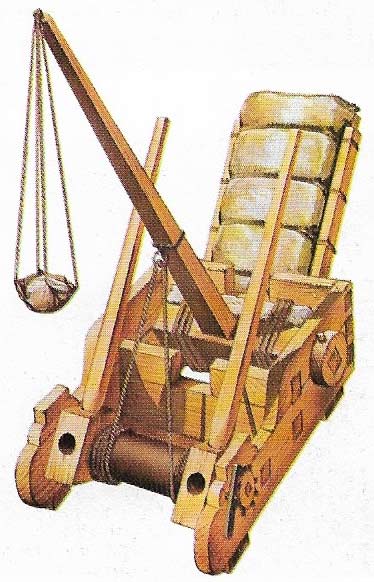

Figure 2. The most powerful catapults of antiquity used the torsion principle rather than the sprung bow. The stone missiles were of varying weights and the artilleryman had to make allowance for this.

Figure 3. The onager, given the same name as a wild ass because of its kicking action, was another kind of catapult that used torsion. The long arm was winched down, and when released it whipped forward against the buffer and hurled the stone.

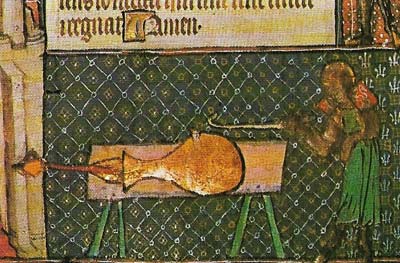

Figure 4. The pot-de-fee, the earliest type of gun used in the West, was first employed in the 14th century. It fired a bolt or heavy arrow. Similar Chinese guns probably fired arrows from bamboo tubes.

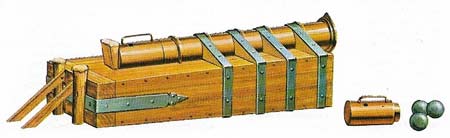

Figure 5. This breech-loading cannon of the late 14th century is from Castle Rising, Norfolk, England. The illustration shows a spare breech and balls. The problem of recoil was a major one at this time.

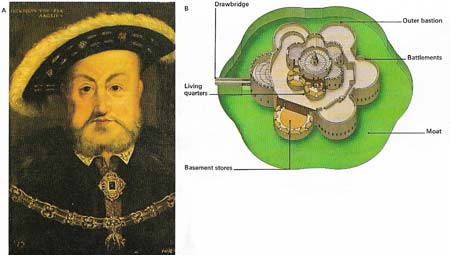

Figure 6. Commanders played a crucial part in developing the technology of artillery. Henry VIII (A) developed the British Navy, founded an arsenal, and took a detailed interest in the development of fortifications (B). He introduced some of his own ideas in fortifications of the north against the Scots and in Boulogne against the French, and encouraged the science of military engineering.

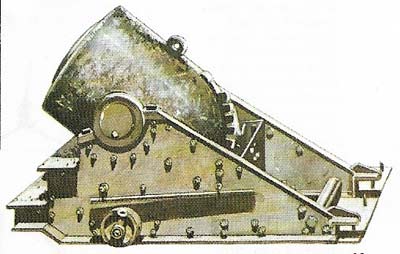

Figure 7. Used in sieges with devastating effect, this 13-inch mortar was deployed by Union forces during the American Civil War.

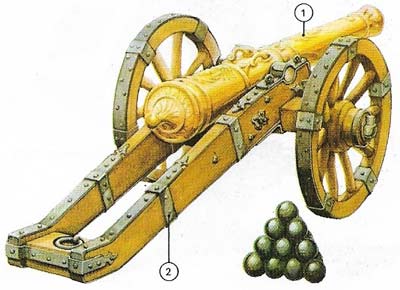

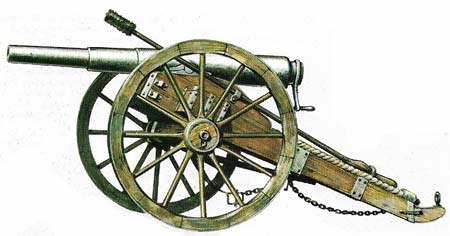

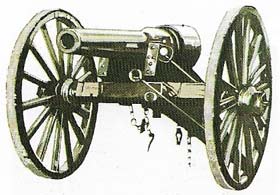

Figure 8. A field piece of this type was used by all armies during the War of Spanish succession (1701–1714). It had a chased and elaborately decorated gun barrel of brass or iron (1) and its gun carriage was reinforced with iron binding (2).

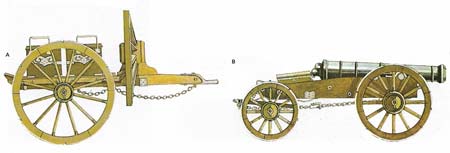

Figure 9. During the Crimean War (1854–1856) this British 18-pounder field gun (B) with its ammunition wagon (A) was used. Much of the allied artillery, however, was of a lighter caliber. Many of the field pieces in use were 9 pounders and some were as much as 40 years old.

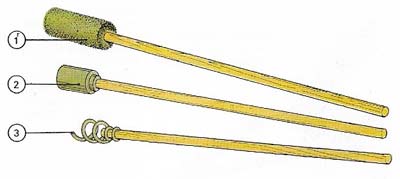

Figure 10. Gun tools of the Napoleonic Wars included a damp sponge (1) – used to get rid of glowing residues in the bore – a rammer (2), which drove the projectile into position, and a worm (3) for removing any obstruction.

Figure 11. Mons Meg, a welded wrought-iron cannon made in about 1460, can still be seen at Edinburgh Castle in Scotland.

Figure 12. The Armstrong 18-kilogram (40-pound) breech-loading gun was used at great expense by the British army be-tween 1859 and 1863, but technical problems caused it to be converted to a muzzle-loading gun.

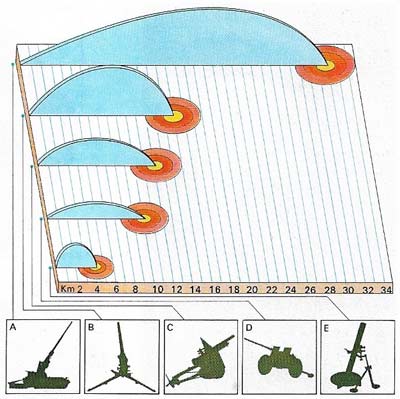

Figure 13. Ranges and trajectories of (A) long-range support guns, (B) howitzers, (C) light support guns, (D) anti-tank guns and (E) mortars vary according to the military functions they serve.

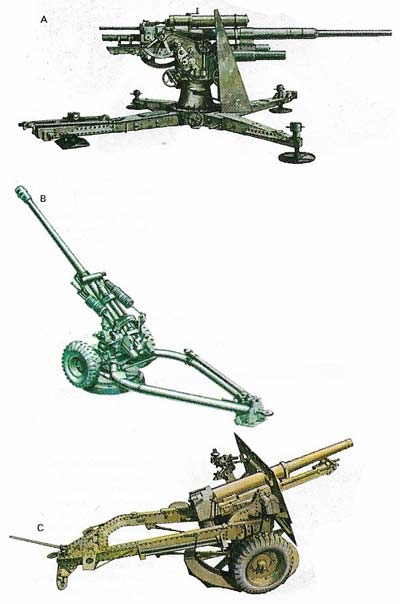

Figure 14. The German 88-millimeter anti-aircraft gun (A) was perhaps the most famous artillery weapon of World War II. During the desert campaigns of 1940–1941 its crews discovered it to be an excellent anti-tank gun. Following this it was then mounted on tanks such as the Tiger, where it was equally effective. The British 25-pounder (C), basically an anti-infantry howitzer, also proved valuable as an anti-tank gun. It, too, lasted the duration of the war. The British 105-millimeter (B) is a close support gun with a range of 2–15 kilometers (1.2–9.3 miles).

Figure 15. The American M-107 was a 175-millimeter self-propelled gun firing a 67-kilogram (148-pound) shell a range of 32 kilometers (20 miles). It was introduced in 1962 as a replacement for big towed guns and was one of the largest SP guns in service. The light chassis, giving a top speed of 54 kilometers per hour (34 mph), necessitated rear recoil spades.

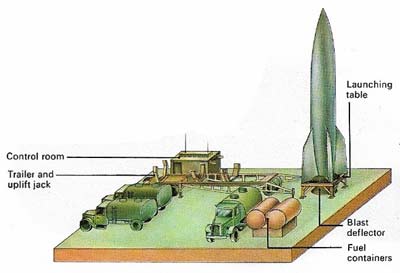

Figure 16. The German V2 rocket was one of the most destructive and sophisticated weapons of World War II. Launched mainly from sites in the Netherlands they killed 2,855 people in England. Built like finned shells, 14 m (46 ft) high and guided by automatic pilots, each carried nearly a metric ton of explosive across a range of 320 kilometers 200 miles) at a top speed of 5,794 kilometers per hour (3,621 mph).

The term "artillery" strictly includes any weapon that projects a missile farther than a man can throw it by hand. But with large missiles, the mechanism used is too heavy to carry, and the definition of artillery is now generally limited to weapons of this type, which have a carriage or mount. A moden artillery piece is generally one of four types: gun, howitzer, mortar, or missile launcher, and is classified according to caliber; ranging from under 105 millimeters for light artillery to more than 155 millimeters for heavy.

The exact origin of artillery using gunpowder is unknown, although such weapons appeared in Europe and the Near East in the 14th century. Used by the Turks to take Constantinople in 1453, artillery changed the whole strategy and tactics of siege warfare. Advances in the nineteenth century included smokeless powder, elongated shells, rifling, and rapid-fire breach loading, and made artillery indispensable in battle.

Early artillery "engines"

All artillery makes use of stored energy that can be released and expended quickly to propel the missile. Before the invention of gunpowder there were three ways of doing this: the compression and tension of fibers, as in a bow; the torsion (twisting) of sinew or fiber as in the catapult; and – much later – the use of a counterweight, as in the trebuchet.

Artillery using the bow principle was known in Syracuse in 399 BC, at about which time a repeating bow firing bolts was developed by Dionysus of Alexandria. Similar weapons were still being used by the Chinese in the 1890s.

A development of the bow, known to the Romans as the ballista, used a single arm inserted into a band of fiber that was tightened by a winch (Figure 2). It could be used to throw a variety of missiles, including stones, Greek fire (a mixture of pitch, sulfur, and naphtha), live or dead prisoners and filth. A ballista had a range of about 500 meters (1,640 feet) and fired a missile weighing up to 150 kilograms (330 pounds). The only siege engine to be invented in the Middle Ages was the trebuchet, which used a heavy counterweight that imparted velocity to the missile.

|

| The trebuchet, a medieval siege weapon, was designed to hurl stones. Also called a mangonel, it worked with a heavy stone counterweight that fell to provide the necessary power. |

Development of firearms

Gunpowder became known in the West about the end of the 13th century. Guns first appeared in Europe in the first quarter of the 14th century and there seems to have been an industry making and exporting guns in Ghent at that time. Early reports of their use in combat include the Siege of Metz (1324), the Battle of Halidan Hill (Scotland) in 1333, and the Battle of Crecy (1346). The first guns fired arrows (Figure 4) and later ones shot stones or balls of cast or wrought iron.

Early light guns were breech-loaders, each with a separate barrel or chamber, mounted on a wooden frame or sledge. These guns were individual pieces with little standardization. Some, such as Mons Meg (Figure 11), were huge and became legends. Mons Meg is 4 meters (13 feet) long, its caliber 49.5-centimeter (19.5-inch) and its weight 5 tons. It fired 150-kilogram (330-pound) granite balls. A weapon known as the Dardanelles gun, of cast bronze beautifully made in two pieces that screwed together, is at the Tower of London. Its length is 5 meters (16 feet), its caliber 63.5 centimeters (25 inches), its weight 17 tons, and the weight of the stone shot 304 kilograms (670 pounds). Tzar Pouchka, in Moscow, cast in 1586 was 5.4 meters (180 centimeters) long, its caliber 91.4 centimeters (36 inches), its weight 38 tons, and the weight of the stone ball 998 kilograms (2,200 pounds). The weight of powder used to fire this monster was 90–136 kilograms (200–300 pounds). In 1544 Emperor Charles I of Spain (1500–1558) limited artillery to seven models, permitting standardization of shot.

The barrels of the first true guns were made from a bundle of wrought-iron rods arranged in a cylinder and welded together. Molten lead was generally poured into the grooves and the whole barrel wrapped in iron hoops. The trunnion, a short stub-axle fitted to the barrel to enable the muzzle to be raised or lowered, was not invented until the mid-15th century. Artillerymen filled cases with small stones or scrap metal, or loaded them loose in the barrel, and used them as anti-personnel missiles. Tactics developed slowly. Initially artillery was used to batter down walls or to fire from walls at an approaching army. Turkish siege guns were largely responsible for the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Between 1537 and 1551 the Italian mathematician Niccol Tartaglia (c. 1500–1577) put forward the first theory about trajectories. He showed that a flying shot follows a curved path – previously gunners had thought that it went straight for a certain distance and then fell vertically downwards. In 1626 Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (1594–1632) tried to devise light field pieces to support his troops. He had his armaments industry make copper barrels bound with iron rings and covered with leather. But these barrels rapidly overheated and therefore could not quickly be reloaded. He also organized his artillery into three roles: field, regimental and siege. This became a fairly standard form of division until 1776 when the French Inspector of Artillery Jean-Baptiste de Gribeauval (1715–1789) grouped them into field, siege and coastal defense. By that time guns were carried on light horse-drawn carriages with second carriages, the limbers, holding ammunition and spare parts.

|

| This muzzle-loading Parrott rifle – a 10-pounder with a 3-inch bore – was used by both sides in the American Civil War (1861–1865). |

Artillery at sea

Heavy naval guns were of greatest use for broadsides at close quarters, although longer-range light guns could be used for harassment. Ships were rarely destroyed by ship-based guns but heavy damage could be inflicted. Pebbles or almost any pieces of iron could be used on land or sea as anti-personnel missiles; grapeshot was bags of round-lead shot. Chain-shot, two hemispheres of iron keyed together and joined by a chain, was particularly effective against masts and rigging. Shore artillery could be far heavier and more accurate. Iron shot was sometimes heated before firing in order to start fires on ships. After loading the main powder charge, the gunners added a small damp charge followed by a red-hot ball.

Developments in the 19th century

There was little change in heavy guns for the 500 years from the time of their introduction in the 1300s to the early 1800s. Their barrels were cast in bronze or iron and they were loaded from the muzzle using black powder (gunpowder). Then the nineteenth century advances in metallurgy and chemistry were applied to artillery.

In 1855 William Armstrong (1810–1900) of England designed a three-pounder gun with a barrel made of wrought iron wrapped round an inner tube. The barrel was rifled to give spin to the shell and therefore greater accuracy and it was loaded from the breech. Many such guns were made in various calibers (Figure 12), but the design was not completely successful. Better was the sliding breech-block, designed by Krupp of Germany, and the interrupted screw system.

In 1888 black powder was replaced by a new propellant explosive – guncotton or nitrocellulose. It burnt more slowly, generating more hot gas and therefore more force. Gun sights were also improved.

In an explosive shell fired from a muzzle-loaded gun the fuse was ignited by the hot gases from the propellant. By 1880 steel projectiles were in general use. A soft metal collar, on a steel shell, called a driving band, sealed it from the gases, thus another type of fuse had to be used. Some detonated when they hit a target and others used clockwork or timed powder trains.

A new explosive for the shell, based on picric acid, was introduced in 1886. The shrapnel shell – a case filled with small steel balls – was invented in 1784 and continued in use until 1916. Breech loading and the new explosives gave rise to "fixed ammunition" with a cap detonator, main propellant charge and the projectile all in one metal case. For calibers of more than about 15 centimeters (6 inches) separate charge and shell continued to be used.

Developments to World War I

A French field gun of 1897 had a device to absorb much of the recoil. As the barrel was forced back by the explosion in it, the movement was arrested by compressing oil in a reservoir; air in a second reservoir was also compressed and its pressure forced the barrel forward again. A spade at the end of the gun carriage helped to keep it steady. This gun, the famous "75" (it had a 75-millimeter caliber), was still in service in World War II. Its flat trajectory, however, limited its use against well-protected installations for which high-trajectory howitzers were sometimes needed.

Britain had a variety of guns: a 13-pounder (3-inch caliber, about 75 millimeters), 4.7-inch and 6-inch guns, and 4.5-inch, 5-inch, 6-inch and 9.2-inch howitzers. Germany used a 77-millimeter field gun firing a 7-kilogram (about 15-pound) shell and howitzers of 42, 105, and 155-millimeter calibers. Nearly all gun carriages were pulled by horses, although there were a few trials using lorries. Some large guns were mounted on railway wagons. The most famous of these was the 21-centimeter (8.3inch) "Paris Gun" with a range of 132 kilometers (82 miles), successful only in its value as an item of propaganda.

Developments in ammunition included poison gas shells (1915) and white phosphorus smoke shells (1916). The high explosive TNT replaced shrapnel. Trench warfare led to the development of the midget howitzer, or mortar. Mortar calibers increased from 75 millimeters (3 inches) to 150 millimeters (6 inches) and even 230 millimeters (9.4 inches) and large mortars evolved into infantry weapons with recoil systems and accurate sights.

|

| Heavy mortars with high trajectories have been important infantry weapons since World War II. |

Developments to World War II

Light close-support guns had been the only addition to artillery since 1918 when war broke out again in Europe in 1939 and lorries began to replace horses. The British used the 25-pounder gun-howitzer, with a range of 12,370 meters (13,400 yards). The United States and Germany had 105-millimeter howitzers firing 4.5-kilogram (10-pound) shells over a range of 10 to 12 kilometers (6.25–7.5 miles).

Improvements in design allowed heavier shells to be fired over greater ranges, and calibers varied from 20 millimeters (0.79 inch) to 800 millimeters (31.5 inches). New fuses exploded shells at a pre-set height above the target. Mountings included wheels, half-tracks and full caterpillar tracks. Special defensive guns were developed for anti-tank use (some self-propelled) and for anti-aircraft (Figure 14).

Then new weapons appeared – rockets that had been tried and abandoned in the mid-1800s. Germans and Americans used Panzerfaust and bazooka anti-tank rockets. Britain and the USA developed a 3-inch anti-aircraft rocket and a 5-inch multiple assembly that could lay 455 kilograms (1,000 pounds) of high explosive per second on a target for nearly a minute. The Russian equivalent was a 130-millimeter (5.1-inch) lorry-mounted multiple rocket system called Katyusha.

After World War II

In the closing stages of the war Germany introduced its two "vengeance weapons", the VI flying bomb and the V2 rocket. The VI was a small pilotless aircraft using a pulsejet engine with rocket-assisted takeoff. It was used to bomb London and nearby targets from launch sites in France and the Netherlands. The V2 (Figure 16) was a supersonic liquid-fuelled rocket carrying a warhead of nearly a metric ton of high explosive. It served as a model for later American and Russian experiments with rockets – soon to be called missiles. For speed of preparation and firing, modern missiles have solid-fuel propellants and, armed with nuclear warheads, they can be fired from underground silos or submarines.