Babylon

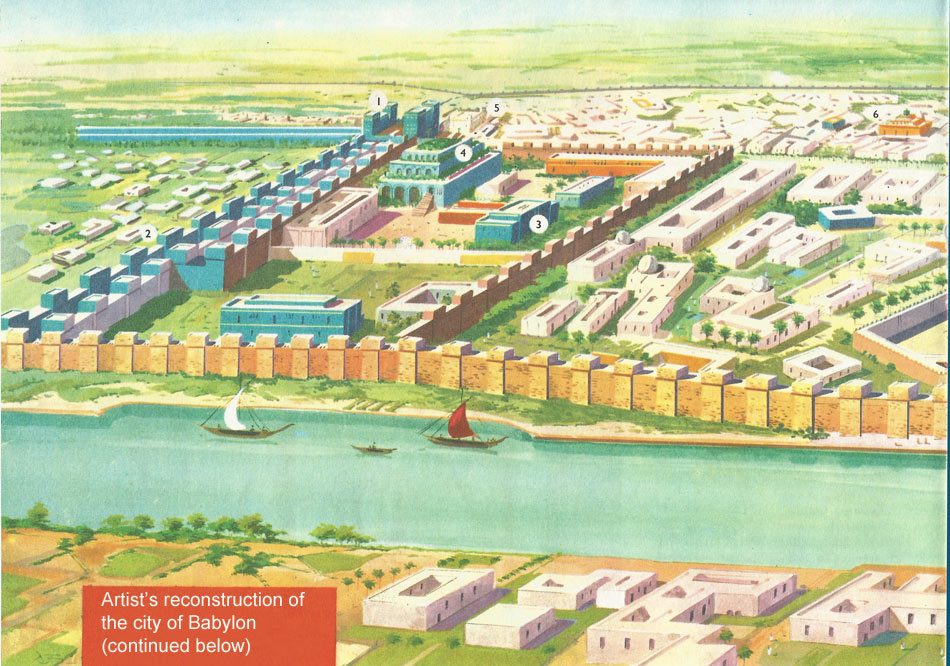

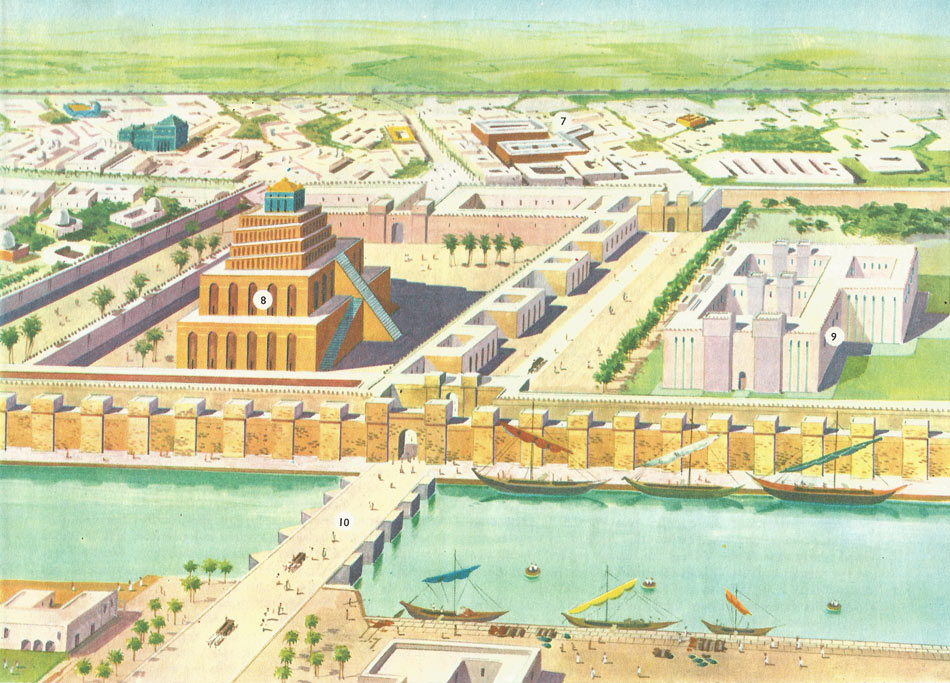

A reconstructed plan of the city of Babylon. The river Euphrates divided the city, and was crossed by a wide bridge.

Plan of the city. The diagram of the city shows the route of the New Year Procession from the Gate of Ishtar to the bridge, and the principal buildings on the east bank of the Euphrates. The Euphrates used to flow through the middle of the city dividing it into east and west sections. Today all the ruins of the city lie on the east bank, so that possibly the river changed its course.

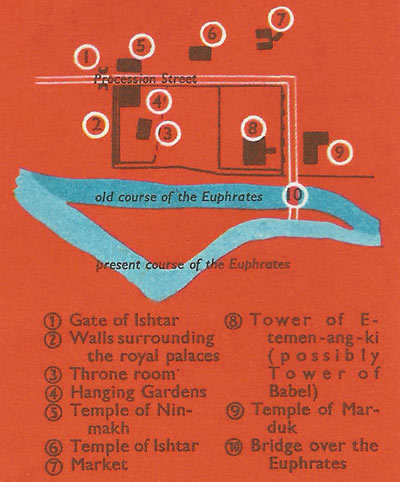

The New Year Procession going through the great Gate of Ishtar to enter Babylon.

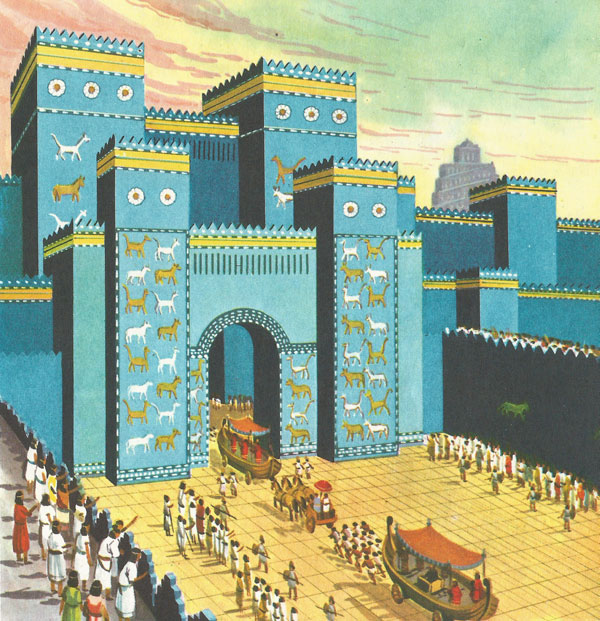

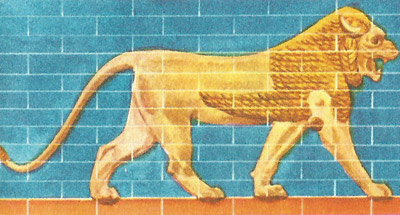

One of the lions that decorated the walls enclosing the Procession Street.

Babylon was the capital of the second oldest civilization on Earth but very little was known about it until 1899, when an expedition of archaeologists and their Arab workmen began to dig up the remains of the great city by the Euphrates. Thanks to the work of scholars, who found the key to the Babylonian language, and of archaeologists, we can form a picture of what Babylon looked like at the height of its power; we know the plan and can reconstruct the wonders of that fabulous city, as it was in about 565 BC.

As the traveller approached Babylon across the plain, the first thing he saw was the golden roof of a huge tower, shining in the sun. Then the great walls came into view, rising sheer from the plain, encircling the city which was over 11 miles in circuit. These walls were wide enough for a chariot drawn by four horses to be driven on their top, and inside lay the Inner City. This was crossed from north to south by the Procession Street, or triumphal way. Every year in Babylon the New Year's festival was held, to celebrate the marriage of the god Marduk (or Bel) with the Earth Goddess, in order to give fertility to the soil and bring good harvests of corn, wine, and olives. The King, the priests, and statues of the gods in their ceremonial wagons, shaped like boats and decorated with gold and lapis lazuli, passed along the Procession Street, which was raised nearly 40 feet above the level of the plain and paved with slabs of marble, three feet square. It was 75 feet wide and flanked with high walls, their foundations laid deep in the ruins of earlier cities. These walls were faced with bricks glazed in brilliant colors, like the bright blue in the illustration, and they were decorated with a frieze of fierce-looking lions, bulls, and dragons, which were meant to frighten away evil from the city. On the underside of each paving slab was inscribed: 'I am Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylonia. I paved the way of Babel with stones, for the procession of the great lord Marduk. Marduk, lord, give eternal life.'

At its north end the Procession Street passed through the Ishtar Gate, with its double portals and gigantic towers. This huge entrance was covered in shining blue glaze, decorated with nine rows of dragons and bulls – 575 in all. When the remains of the gate were discovered, within living memory, 152 of these animal figures were still there in their original positions, and enough of the ancient building had survived to show what it must have looked like.

Following the New Year's Procession through the Ishtar Gate, the traveller would find himself in the Inner City. Here were splendid palaces and stately temples in their enclosures, and here were narrow streets of flat-roofed, yellow-brick houses, with no windows looking on to the streets, strongly built with brick floors, and a water supply obtained from many circular wells. Here, too, was the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, with its great courtyards, its vast throne room, and scores of smaller rooms, enclosed by high walls studded with towers; the temple of the goddess Ninmakh, its bricks covered with white plaster which shone like marble in the sun; and another royal palace of bright yellow brick decorated with blue enamel, with floors of black and white stone, and huge carved lions guarding the entrance. Most spectacular of all were the Hanging Gardens. The word 'hanging' is misleading, for the gardens were laid out in terraces built in tiers over arches, and planted with oak, ilex, pine, plane, willow, ash, palm, orange, and pomegranate trees. The whole structure was about 75 feet high, with steps ascending from tier to tier, and it was kept cool and fresh all the year round by water pumped from a well below ground level. Nebuchadnezzar is said to have planned the gardens as a present to his queen, Amyhia, a Median princess, so that she should not miss the hills of her own country living in the flatness of Babylonia.

Near the center of the city stood the great tiered tower with its roof of gold, the highest building in Babylon. This was E-temen-ang-ki, the temple of Marduk, probably the original Tower of Babel in the Old Testament, though some scholars think that this was another tower at Biss Nimrud. A legend of Babylon told that the god Marduk commanded Nebuchadnezzar's father, Nabopolassar, to build the tower, laying its foundations in the underworld, while the summit stretched up to heaven. Round the tower in its huge square enclosure were the priests' dwellings, hundreds of guest rooms for strangers visiting the shrine, and the treasuries containing fabulous riches. The Babylonian temples were immensely wealthy, owning property, acting as banks to the citizens, who paid dues to them, and even supplying the kings with money in time of war. But their coffers of gold and silver attracted foreign invaders and they were guarded by strong walls, strengthened further by towers.

The tower itself was 300 feet high, growing more slender towards its summit in a series of tiers. Its triple staircase led to shrines dedicated to the chief Babylonian gods.

After the excavation of Babylon at the beginning of the twentieth century, almost every single brick of the tower which remained was carried off by local builders, and nothing is left now except a lake full of reeds. To the south of the tower lay another large temple of Marduk, enshrining a statue of the god. A little way off, east of the Procession Street, lay a smaller temple of the goddess Ishtar, called in the Bible 'Ashtoretti'.

The Procession Street skirted the long east wall of the temple enclosure, rounded the tower, and then turned westwards, crossing the Euphrates by a massive stone bridge and passing on into the western quarters of the city. Beyond the city walls were fields of wheat and vineyards, groves of olives and palms, where today there is only desert.

The site of Babylon was known for centuries after its decline, first under Persian rule, then for a short time as a city of Alexander's empire. Many travellers passed and often lingered by the huge mounds of mud-brick beside the Euphrates. But in the 19th century, when serious excavation began in this part of the world, British and French archaeologists were more interested in Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, than in Babylon. It was not until 1899 that a German expedition, led by Dr. Koldewey, began the final excavation in Babylon. This tremendous task was interrupted in 1914 by World War 1, but already the whole lay-out of the imperial city had been excavated, and the position of its fortified walls, gateways, the Procession Street, and chief buildings had been traced.

Unfortunately the ruins of mud-brick walls, whether the bricks are baked or dried in the sun, cannot be preserved once they have been exposed to light and air. The traveller today can see the outline of the largest structures, the sheer size and bulk of which have withstood time, but the rest is desolation.