Babylonians 2000 to 323 BC

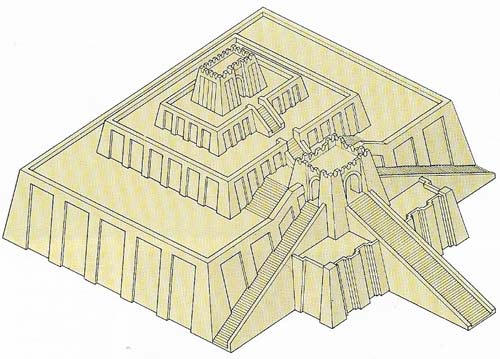

Figure 1. The great ziggurat of the moon god at Ur (top) was begun, according to King Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC), by Ur-Nammu (r. 2113–2096 BC), but may well conceal the remains of an older tower from as far back as the predynastic period. Nabonidus says it was continued but left unfinished by Ur-Nammu's son Shulgi; Nabonidus himself made good the stairways with new treads a meter above the old and raised the level of the terrace. Different in many respects from the Mesopotamian ziggurats, and the largest known – 100 meters (328 feet) square – is the ziggurat at Dur-Untash in Elam (bottom), near Susa.

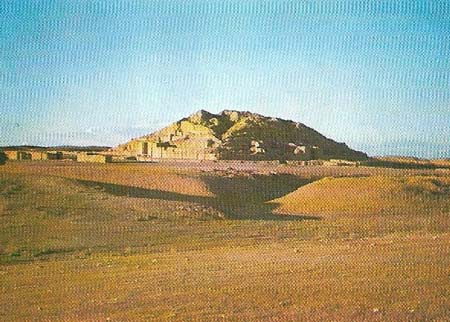

Figure 2. This Babylonian tablet, not yet fully understood, appears to be concerned with theoretical geometry. Most Babylonian mathematical texts are contemporary with the dynasty of Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BC); the rest are datable to the last three centuries BC. The earlier history of the Old Babylonian group is not known, beyond the evidence of innumerable economic-administrative texts from the earliest period of Mesopotamian writing, whose number system, based on 60, was retained by the Old Babylonians. But although the content of Old Babylonian mathematics reached a level which can be compared with that of the early Renaissance – it was elementary compared with that of the Greeks.

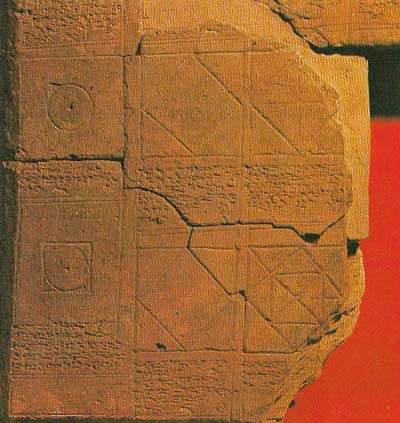

Figure 3. Relief bricks from Babylon, some showing bulls and mythical creatures, once formed part of the Processional Way.

Figure 4. Babylon dominated western Asia, more or less, for thirteen and a half centuries. It lay on the lower course of the River Euphrates, an advantage much increased by the development of irrigation systems.

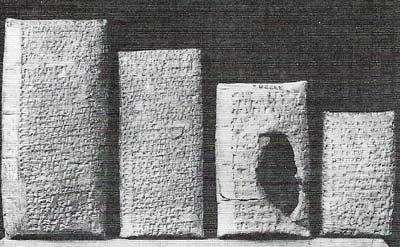

Figure 5. Early clay tablets reveal the importance of sheep and goats – they also use the signs for merchant, cattle, and donkey – in the economy of early Sumerian communities. The Akkadian period improved on the quality of the early tablets in the first-ever recording of a Semitic language – Old Akkadian. Their development into the tablets of Babylonia (those shown are Old Babylonian) and Assyria culminated in the calligraphy of the scribes of Assurbanipal's library at Nineveh.

Figure 6. Naram-Sin (c. 2254–c. 2218) of Akkad, whose Semitic line was an interlude in Sumerian history presaging the supremacy of the Semitic Babylonians, portrayed himself on this stele triumphing over the eastern Iraqi king of Lullubi.

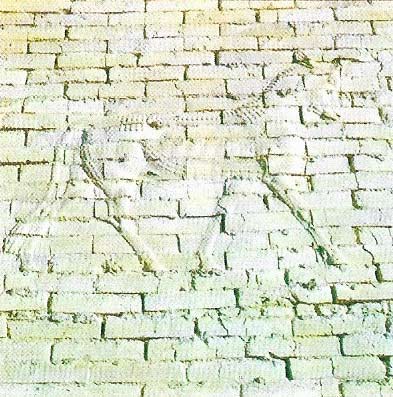

Figure 7. The throne-base of Shalmaneser III found at Nimrud has an inscription on the horizontal surfaces. It includes a separate section referring to the king's campaigns of 851 and 850 BC in Babylonia, in which he helped the Babylonian king to defend his throne against a rebellion. This relief carving on the western vertical face shows Shalmaneser (right) and probably the Babylonian king (left), each with an attendant, under a canopy. They are shaking hands – a unique representation in Mesopotamian art of this modern gesture; whether it implies equanimity, Babylonian subservience, or neither, is unknown.

The ferocious sacking and fall of Ur in 2006 BC allowed the Semitic-speaking Amorites under Ishbi-Erra to establish more effectively a dynasty that ruled at Isin for more than two centuries. A few years earlier another Semitic-speaking dynasty arose at Larsa, of slightly longer duration; and the two dynasties in parallel dominated Babylonia for a century until a third power was established – unopposed by them – consisting of more Semitic-speaking Amorites at Babylon early in the nineteenth century.

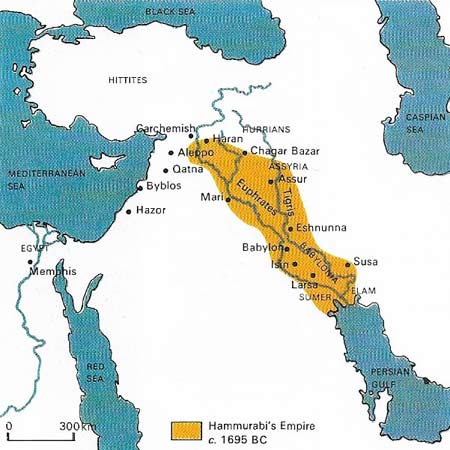

However, early in the 18th century BC, Larsa, under Rim-Sin "the true shepherd", overcame Isin and became the sole major contender with Babylon for the domination of the land (Figure 4).

|

| With, with talons and feathered legs, was a Babylonian-Assyrian goddess who survived in Jewish lore into the Christian era. Traditionally a sinister bringer of death, in this clay relief she holds what may be a measuring rope to indicate the span of man's life. She is mentioned in an early fragment of the Epic of Gilgamesh, which also gives some independent evidence corroborating the biblical Flood. The profile used in narrative reliefs was less suited to representing the deity in actual rites; and reliefs over the altars of shrines show the goddess in a frontal view, perhaps to establish a relationship with the worshippers. |

Hammurabi and his laws

The first five kings of the new dynasty at Babylon were mainly preoccupied with defensive and religious building and by canal-clearing, with little extension of territory. It was left to Hammurabi to engage in victorious campaigns that left his empire stretching from Mari on the Euphrates in the northwest to Elam in the east, and by defeating Larsa to succeed to the traditional "kingship" of Sumer and Akkad.

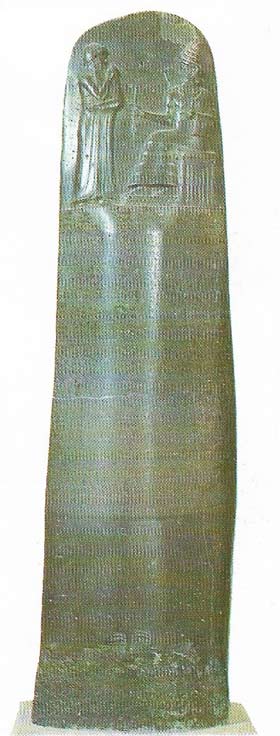

Apart from his achievement of this relatively ephemeral empire, Hammurabi's fame rests mainly on his code of laws, written in Akkadian, a Semitic tongue that had by then – in parallel with political developments – become the principal language of Mesopotamia. Sumerian was retained mainly for religious use, although the civilization it expressed was absorbed by the Semites and continued to flourish.

|

| The diorite stele of Hammurabi was carried off from Babylon by an Elamite invader, perhaps in the 12th century, and taken to Susa, where it was found in the winter of 1901–1902. The text is topped by a bas-relief showing Hammurabi receiving the commission to write the laws from Shamash the sun-god of justice. The Elamites apparently chiseled off parts of the text, but most of these survive on other copies of the code. It has a prologue and an epilogue in semi-poetic style. |

No evidence has yet been found for the application of Hammurabi's laws in contemporary documents, nor was any appeal made to them; their standing and function are therefore unclear. But they may well have been an attempt to unify practice – notably in land tenure – among diversely regulated areas, with more uniform arrangements perhaps already prevailing in some matters not covered by them.

The reigns of Hammurabi's successors were long and undisturbed, and although in the later 18th century BC mention was made in Babylon of the alien Kassites (probably from the mountains in the northeast, and possibly Aryans), it was evidently an attack by the Hittite king Mursilis I in or soon after 1595 BC that brought the long-remembered destruction of Babylon and the downfall of Hammurabi's dynasty. But Mursilis can hardly have contemplated permanent con-quest, and the void was filled by a Kassitc dynasty later credited with a 576-year rule.

The dark ages of Babylon

Babylonia absorbed the Kassites, and during a dark age of more than 200 years little was heard of them. In the mid-fourteenth century BC the Kassite king married the daughter of the king of Assyria. But the alliance led to wars that resulted in the temporary conquest and occupation of Babylonia by the outstanding Assyrian soldier-king Tukulti-Ninurta I in 1235 BC. Essentially the Kassites retained Babylonia, but their dynasty fell to the Elamites in 1157 BC.

The Elamites lost political control of Babylonia before the end of the century; it passed to a second dynasty of Isin which, under Nebuchadrezzar I (reigned 1124–1103 BC), ended Elamite interference. The Isin Dynasty fell after little more than 100 years of political stability. The ensuing age of uncertainty and civil disturbance was relieved by the inauguration of the Eighth Dynasty of Babylon in 977 BC, and for a century Babylonia maintained close contact with the developing power of Assyria.

Shalmaneser III (Key) of Assyria (reigned 858–824 BC) was called upon to help quell a rebellion in Babylonia, at which time the powerful Chaldaean tribes of southern Babylonia were first making their appearance. Wars with Assyria and anarchy at home preceded the emergence of Tiglath-Pileser III (reigned 744–727 BC) as a strong king of Assyria who at length assumed the Babylonian crown. His successor Shalmaneser V (reigned 726–722 BC) ruled both countries for five years, but both. Sargon II (reigned 721–705 BC) and Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 BC) found strong antagonists in the Chaldaeans.

Babylon's fortunes varied widely in the 7th century, until the rise of the unknown "son of a nobody" Nabopolassar (reigned 625–605 BC) inaugurated a great age of Babylonian civilization under the neo-Babylonian or Chaldaean Dynasty.

The rise of the neo-Babylonians

Babylon helped the Medes in the overthrow of Nineveh and the Assyrians in 612 BC. Her brilliant commander Nebuchadrezzar II (reigned 604–562 BC) destroyed Jerusalem and carried off its inhabitants, erected great monuments and buildings, which made Babylon one of the Seven Wonders of the world – this is the period of the "Hanging Gardens".

Nebuchadrezzar's son was murdered, and the decay of Babylonia accelerated under the pious antiquarian Nabonidus (Figure 1); Babylon fell without a fight before the Achaemenid Persian king Cyrus the Great (c. 600–529 BC) in 539 BC. Xerxes (c. 519–465 BC) partly destroyed it in 482 BC; it might have been restored by Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) had he not died there, and thereafter, although its astronomical schools survived, Babylon passed into history.