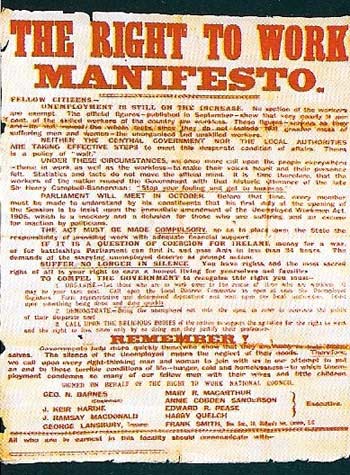

British labor movement 1868 to 1930

Figure 1. The London dock strike (1889), the first major action of its kind by unskilled workers, lasted five weeks. It ended in victory for the dockers who won their claim for a basic 6d (2½ p) an hour (the "dockers' tanner"). The most significant aspect of the strike, however, was the widespread support won by the dockers from skilled workers and other sectors of the community. The dockers advertized their case skillfully and thus notably advanced the cause of working-class solidarity. Their militancy also highlighted the spread of socialism among British workers.

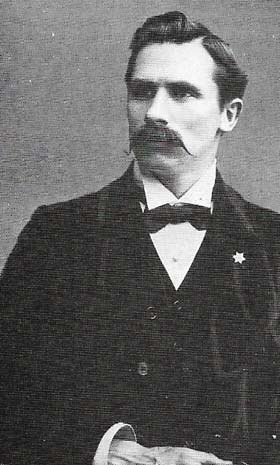

Figure 2. James Kier Hardy was one of the leading and best-loved figures of the British labor movement. Born in Lanarkshire, Scotland, he worked as a coal miner from the age of 10, and in 1886 formed the Scottish Miners Federation. He was the first chairman of the Scottish Labour Party (1888), and in 1892 became the first workers' representative in Parliament when he was elected as an independent Labour MP. Through his tireless efforts he was involved in the foundation of the Independent Labour Party in 1893, and the Labour Representation Party Committee in 1900. He lost his seat in 1895, but was re-elected in 1900 as Labour MP for Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales which he held until his death.

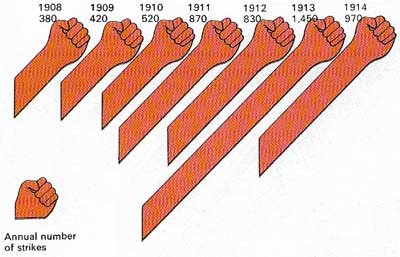

Figure 3. In 1908 there were 380 strikes; in 1913 there were 1450. Dockers, seamen, railwaymen, and miners all struck between 1911 and 1914. There were militant and bitter conflicts and the men often held out for long periods in support of their demands. The strikes were prompted by various factors: the restoration of trade unions' legal immunity in 1906, falling standards of living, the apparent failure of the Labour Party to protect the interests of the working class, and the growth of Marxist and syndicalist ideas among working men. With the onset of the war in 1914, unrest declined because most union leaders and members chose to back the war effort.

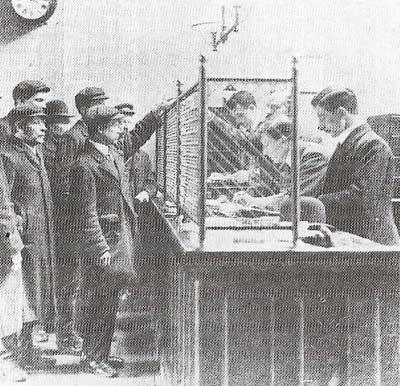

Figure 4. Labor exchanges were introduced into Britain in 1910 by Winston Churchill (1874–1965), then Liberal President of the Board of Trade. Advocated by the Poor Law commission of 1909 and by the economist William Beveridge 1879–1963), labor exchanges were intended to provide service for workers seeking employment and for employers seeking labor. They also prepared the way for a national system of social insurance. Initially, they were not as effective as had been hoped. Registration of unemployment was not compulsory so that only one-third of vacancies were filled through the nationwide exchanges.

Figure 5. The 1926 General Strike lasted nine days (4–12 May). In the face of government resistance the trade Union Congress ended the strike. The miners held out, in vain, until August.

Figure 6. By the 1870s trade unions had achieved legal recognition. Until that time unions had followed no specific political viewpoint, but from the 1880s the movement took a new turn. Disillusioned with the Liberal Party and influenced by socialist ideas, the "new unions" increasingly stressed the political role. They demanded a legal minimum wage, an 8-hour day, and the right to work. Although union militancy continued until well after World War I – until its defeat in the General Strike of 1926 – with the establishment of the Labour Party by 1906 union activity increasingly followed more conventional, parliamentary channels.

The driving force behind the British labor movement in the latter half of the nineteenth century was the trade unions, which had been given restricted legality in 1825. Until the advent of the so-called "new unionism" in the 1880s, most trade unions were associations of skilled workers of varying political allegiance. Nonetheless, by the 1880s they had established a relatively secure position for themselves. In 1871 trade unions had been given legal recognition and in 1875 peaceful picketing was legalized.

|

| The London match girls came out and strike in 1888. Their appalling working conditions had previously been exposed by the Fabian lecturer Mrs Annie Besant (1847–1933) in her paper the Link. With her help and that of other Socialists, the match girls were eventually victorious and won recognition for their union. This was one of the first examples of the wave of "new unionist" activity and organization that spread among the semi-skilled and unskilled workers from 1889. It clearly indicated the bad conditions that had to be endured by these people who made up by far, the bulk of the British working class. |

New unionism

The period from 1875 to 1900 saw rapid growth in trade unions. This resulted partly from the rising prestige of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) which was founded in 1868, and partly from the efforts of a generation of "new unionists" who preached a much more militant form of trade unionism and organized semi-skilled and unskilled workers, such as dockers and gas workers, into new, industrial unions (Figure 6). These unions were prepared to take strike action with much less hesitation than before (Figure 1). The result was the growth of working-class solidarity, an increasing dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party and the spread of genuinely socialist ideas among working men.

The growth of socialism had been demonstrated in 1888 when James Keir Hardie (1856–1915) and R. B. Cunninghame Graham (1852–1936) founded the Scottish Labour Party. It was given national expression in 1893 when Hardie (Fig 2) founded the Independent Labour Party (ILP) with the aim of encouraging trade unionists and socialists to join forces for the creation of an independent political party with working-class representation in Parliament. A non-revolutionary path to socialism was also sought by the Fabian Society which was founded in 1884. Among its best known exponents were Sidney (1859–1947) and Beatrice (1858-1943) Webb and the writer George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950). In 1900 the Fabians, with the ILP, the Marxist Social Democratic Federation and trade unionists, set up the Labour Representation Committee (LRC). Its aim, to quote Hardie, was to form a distinct Labour group in Parliament. Its first secretary was James Ramsay Macdonald (1866–1937).

|

| Tom Mann (1856–1941) was one of the leading "new unionists" of the late 19th century. In 1881 he joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and by 1886 had become involved in the socialist movement. In that year he published a pamphlet arguing that a more militant attitude should be taken by trade unionists. In 1889 Mann helped to organize the London dock strike and from 1894–1897 was secretary of the Independent Labour Party. He emigrated, and in 1902 was active in the Australian labor movement. In the 1920s, after his return to England, he became a founder of the British Communist Party, feeling that the existing unions could not be militant enough. |

The LRC's program was a moderate one – it avoided commitment either to socialism or to the class war. As a result, in 1901, it lost the support of the Marxist Federation, but it did gain considerable trade union support, largely in reaction to the Taff Vale decision by the House of Lords in 1901 which found trade unions liable for losses incurred through strikes. In 1906, therefore, the LRC saw 29 out of 50 of its candidates elected to Parliament; later that year, the LRC was renamed the Labour Party.

The growth of the Labour Party

From 1906 to 1914 the Labour Party supported the social reforms of the Liberal governments, which in turn passed legislation benefiting the trade unions. The Trade Dispute Act of 1906 reversed the Taff Vale decision of 1901 and the Trade Union Act in 1913 allowed trade unions to support the Labour Party financially. Nonetheless from 1910 to 1914 trade union militancy increased (Fig 3) as a result of rising prices and the spread, from France and the United States, of syndicalist ideas that advocated a general strike to destroy capitalism.

The Labour Party continued to cooperate with the Liberal Party in Parliament and during World War I Arthur Henderson (1863–1935), who succeeded MacDonald as leader of the Labour Party in 1914, sat in the war cabinet of the coalition government. Various other Labour members also held administrative posts. By 1918, however, the Labour Party stood for a more independent policy, and influenced by events in Russia, adopted a more socialist constitution.

After the war the Labour Party soon became the second party in the country. Disillusionment, unemployment, and political strife within the Liberal Party meant that the Labour Party became the official opposition in Parliament in 1922. In 1924 Ramsay Mac-Donald became prime minister at the head of a minority government. His administration lasted only ten months. Publication of the so-called "Zinoviev letter" – instructions for a communist uprising in Britain apparently sent by Gregori Zinoviev (1883–1936), chairman of the Communist International – severely damaged the Labour Party. Although the letter was later proved to be forged, Labour fell before the Conservatives in November 1924.

|

| Ramsay MacDonald was the Labour Party's first prime minister. In 1894 he joined the Independent Labour Party and was its chairman from 1906–1909. He helped to found the Labour Representation Party and in 1924 became the first Labour Party premier. In 1929 he again became prime minister but was rejected by the Labor Party when he formed a coalition national government in 1931, the only way he saw of keeping Labour in power. |

The second Labour Government

In 1926 the trade unions challenged Conservative rule when the TUC supported the General Strike on behalf of the miners (Figure 5) but the government successfully resisted the challenge and in 1927 outlawed general strikes and attempted to reduce trade union subscriptions to the Labour Party.

In 1929, with the onset of the Depression, Labour returned to office with Ramsay MacDonald once again at the head of a minority government. His cabinet was di-vided over economic policy. Because socialist legislation was impossible in the midst of the economic slump, in 1931 MacDonald formed a coalition national government. In doing so he forfeited the support of the Labour Party, whose parliamentary representation dropped sharply in the 1931 general election.