Byzantine Empire

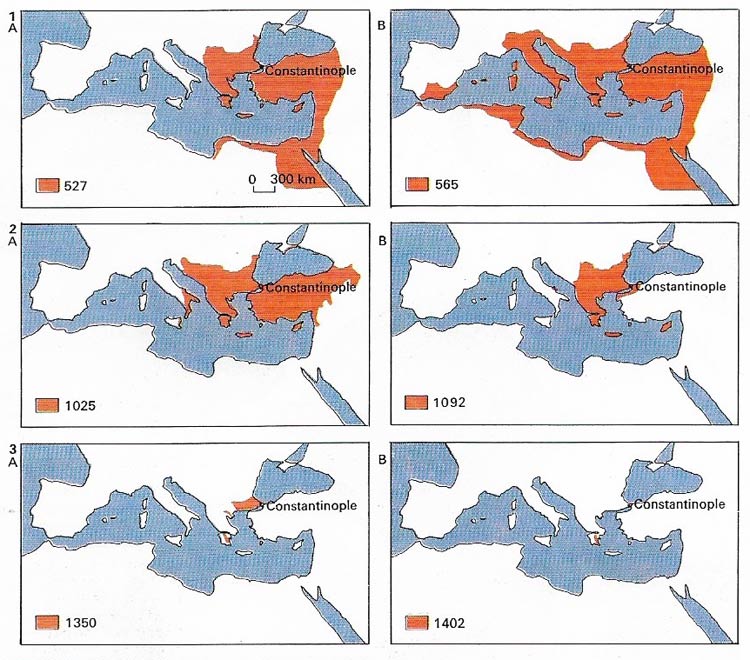

Figure 1. (1) The Byzantine Empire under Justinian I grew from an exclusively Eastern power in 527 (A) to an empire controlling by 565 many former territories of imperial Rome (B). Germanic invaders were ousted from many areas of the Mediterranean. (2) The recovery of many areas which the empire had lost to the Slavs, Germans and Arabs in the 7th and 8th centuries was completed by the conquests of Basil II ("the Bulgar slayer") (A). But Normans and Turks had made large inroads by 1092 (B). (3) Dismembered by Turkish attacks and by internal feuds. The empire had shrunk in 1350 to a corner of the Balkans and some land in Greece (A). By 1402, even the Balkan territory was lost (B) and Constantinople was soon to fall.

Figure 2. A patrician couple in the 6th century has a similar social status to their traditional Roman counterparts. As a middle class emerged, mobility between plebeian and patrician classes was higher than in Rome.

Figure 3. Justinian I (reigned 527–565) is the central figure on a glowing mosaic from the Church of St Vitale, Ravenna. Justinian made a determined effort to reunite the old Roman Empire under Christianity. Byzantine churches, such as at Ravenna were built after Justinian's general, Belisarius. Overran Italy as far north as Milan in the years following 535. Justinian's military, cultural and administrative achievements earned him the title of "The Great". His consort, Theodora, daughter of an animal keeper, was influential in Byzantine court politics.

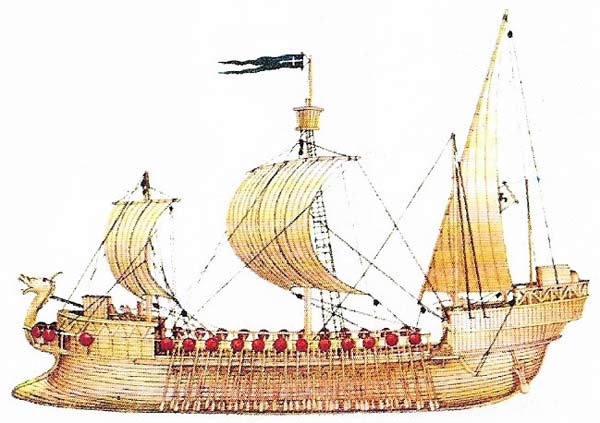

Figure 4. The dromon was a Byzantine development of the traditional Greek galley. Much Byzantine trade was carried by sea and the empire kept large and efficient mercantile and naval fleets. The dockyards along the Marmara coast were the finest found in Europe until the 12th century.

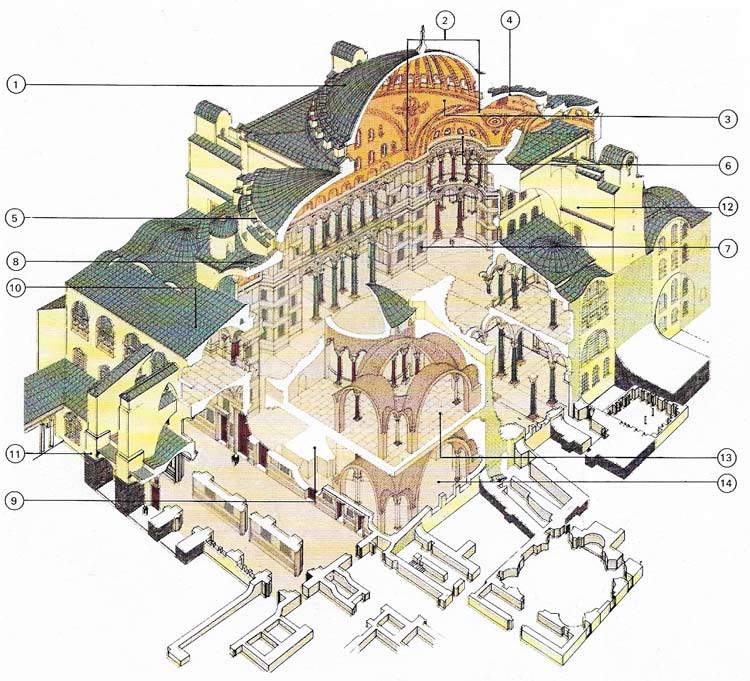

Figure 5. Haggai Sophia (Church of Holy Wisdom), built during the reign of Justinian I, was completed in only five years. Intended to provide a spiritual center for the empire, it is the largest Christian church in the Eastern world and is exceeded in splendor only by St Peter's in Rome. The most famous of many architects who worked on the project were Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. The overall design shows little classical influence, although Justinian despoiled classical buildings on Athena, Ephesus, Rome, and Baalbek for marble. Technically, the most striking feature is the massive central dome (1) which measures 31 m (100 ft) across. Its thrust is borne by four arches (2), joined by pendentives (3) which separate the semi-domes (4 and 5). Lesser semi-domes (6) flank the main piers (7). The thrust from (5) is taken at the west by an arch (8) supported on piers (9). Vaulting (10) transfers the outward thrust to a series of flying buttresses (11). Buttresses (12) support the dome's north and south thrust. By building domes on arches (13 and 14), large areas could be spanned. The exterior brickwork is plastered. Brick domes and semi-domes are lead-covered. Interior walls, piers and floors are clad in various marbles, and vaults and domes in rich mosaics. The church was used as a mosque after 1453 and has been a museum since 1933.

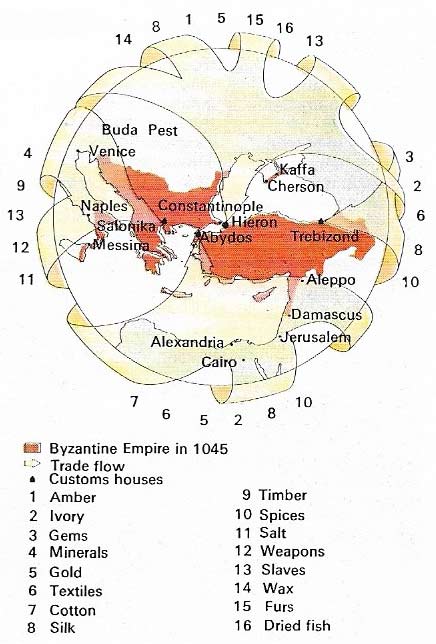

Figure 6. Major trade routes of the 11th century reached a natural junction at Constantinople and the city became a great east-west market. A duty of 10% was levied on imports reaching Hieron from the Black Sea, Abydos from the Mediterranean, Trebizond from Asia, and Salonika from the Balkans. Byzantine craftsmen were famed for their working of gold, silver, amber, ivory and all kinds and of precious stones.

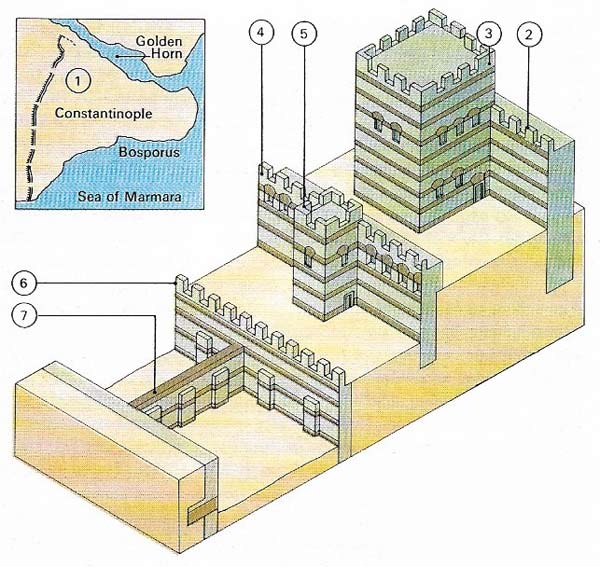

Figure 7. Constantinople's walls, built across the peninsula (1) in the 5th century, were defensible at varying levels. The main wall (2) had 96 outlook towers (3). From a second wall (4) a tower (5) gave defended access to a moat wall (6). Sluice gated (7) controlled water in the moat.

In AD 293, the Emperor Diocletian decided, for military and administrative reasons, to shift the center of the Roman Empire eastward. From its origin as a new Rome, the Byzantine Empire became a vital trade and cultural link between Europe and Asia and a bastion within which Greco-Roman civilization developed new and magnificent forms. Byzantium later found itself in doctrinal and political conflict with the Western popes and emperors but, as a Christian empire, it resisted Arab, Slav, and Turkish invaders for more than 11 centuries.

The founding of Constantinople

Both Diocletian (245–313) and Constantine I (c. 285–337) sought a better base than Rome, closer to the troop-recruiting grounds of Anatolia and the Balkans. Constantine's choice fell upon a town on the Bosporus which had been the site of an ancient Greek city, Byzantium. Constantinople, as the new capital was called, had a fine harbour and was almost unassailable (Figure 7). The scale on which it was conceived surpassed anything in the ancient world. Constantine was determined to found an urban center to which men throughout his empire could direct their loyalties. He believed a common religion could also provide a powerful cohesive force. He had been converted to Christianity in 312 and in 330 dedicated Constantinople to the Virgin Mary.

The close association of Church and state and the prestige and near impregnability of the capital gave an eastern sector of the Roman Empire remarkable unity after Theodosius (346–395) left the empire split into two.

While the Western Empire was swept away in 476, the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire was able to resist attack on the Balkans by the Visigoths and Ostrogoths. In the 4th and 5th centuries an intellectual elite created the science of theology from Greek logic and the Christian revelation.

Although theology helped to strengthen the people's faith, it also led to religious discord. Many of the Byzantine Empire's later problems can be attributed to factional struggles in which theological differences hardened into political ones that could be exploited by invaders. The Christological controversy, which came to a head in the fifth century, was concerned with the relationship between the human and divine aspects of Christ's nature. The followers of Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, stressed the human side while the Monophysites, based as Alexandria. Stressed the divine. An equally bitter controversy, which reached its height in the 8th century, was iconoclasm – opposition to the worship of images.

The Justinian era

The Empire reached its apogee under Justinian the Great (c. 482–565), a brilliant administrator with wide-reaching military ambitions (Figure 3). His general, Belisarius, reasserted Christian-Roman authority over large areas of the former Western Empire. Justinian greatly expanded the capital and built Hagia Sophia (Fig 5) which was intended to provide a center of worship for all Christendom. Perhaps Justinian's greatest achievement was the codification of Roman law. His Codex Justinianus remained in the Middle Ages the main legal source book in Europe.

Byzantium nevertheless became increasingly Greek in character after reign of Justinian and Greek replaced Latin as the official language. The conquests in the west were short-lived and the ravages of plague weakened the empire's ability to resist Persian attacks in the east. Aided by dissident Monophysites, the Persians had occupied most of Egypt, Syria and Palestine by 615. A greater menace appeared in 637 when the Arabs, five years after the death of the prophet Mohammed, overran Syria and Palestine. Later they took North Africa, Sicily and the important grain lands of Egypt while their fleets secured Cyprus, Rhodes and several other islands.

|

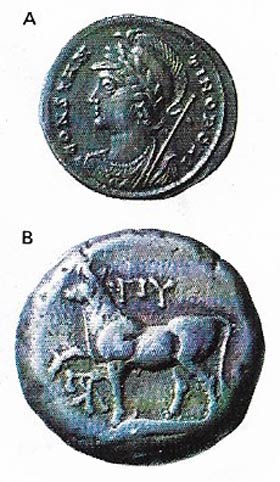

| Byzantine coins reflected a change to a predominantly Greek culture after the 7th century. The Latin inscription on gold solidus (A) gave way to one in the new official language of Greek (B). |

Revival and decline (867–1453)

At its boundaries shrank, the empire regained its ethnic unity and acquired renewed strength. From 867, under a Macedonian dynasty, it took the initiative against the Muslims and by the time of the death of Basil II (958–1025) its borders reached from the Danube to Crete and from southern Italy to Syria (Figure 1(2)). During this last period of greatness, trade flourished (Figure 6) and missionaries spread Christianity throughout the Balkans and into Russia.

The Turks were soon to bring the empire to its knees, however. The defeat of Romanus IV by the Seljuks in 1071 and subsequent capture of Anatolia were the beginning of the end. From then until 1453 the empire was steadily eroded by intrigues, attacks and religious conflicts (Figure 1(3)). The Crusaders, whose help was enlisted against the Seljuks, fell out with the Byzantines and exploited a quarrel to take Constantinople in 1204 and set up a number of semi-independent Latin states. Religious schisms and trade rivalries prevented any concerted western effort against the Ottoman Turks who made Byzantium a vassal state in 1371. Although only Constantinople and a few outposts along the Sea of Marmara remained by 1453, it took the Sultan Mehmet II (1431–1481) nearly two months to capture the great city itself. With his final victory the old Byzantine world from the Balkans to Palestine was once again united, this time under the Ottoman state, which dominated the Mediterranean for the next 200 years.

|

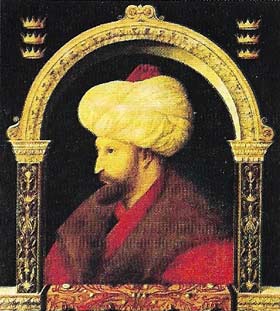

| Sultan Mehmet II gave the Ottoman Empire a European outlook when he took Constantinople in 1453 and made it a center of learning and religious tolerance. Although autocratic, he was a gifted administrator. Gentile Bellini, who painted this portrait, was one of several Italian artists he patronized. |