Celts 500 BC to AD 450

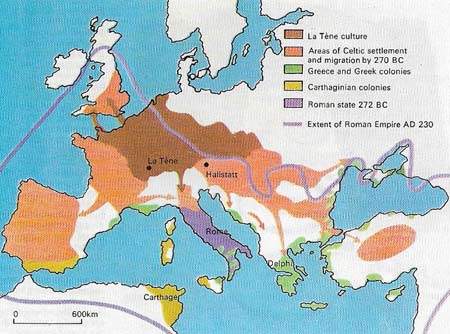

Figure 1. La Tène, a key archeological site in Switzerland, is the name given to the period of Celtic culture in Europe that lasted from approximately 500 BC until the time of Roman expansion during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. As the map shows, by about 270 BC the Celts had migrated into France and the Iberian Peninsula, parts of the British Isles and to some extent eastwards into central Europe. From this time, however, they gradually lost ground to Rome. By the mid-1st century BC the Roman dominance was assured.

Figure 2. This silver-covered iron votive torque (bracelet) weighs about 6 kg (13 lb). Both ends have sacred ox heads, each with its own twisted necklace. Too heavy to be worn, it was probably hung on a stone or wooden divine image. It comes from Trichtingen, Wurttemberg, in Germany.

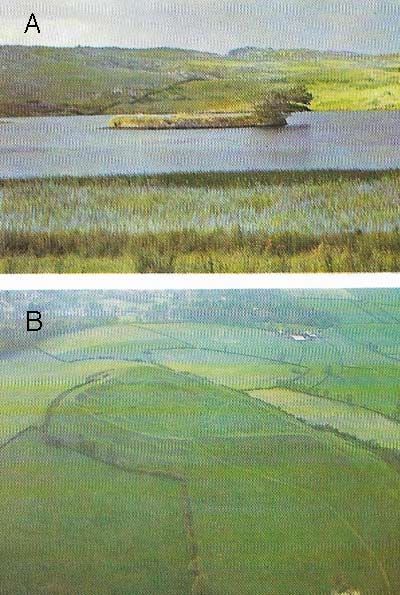

Figure 3. Warfare was the main influence on Celtic architecture. Fortified dwellings built for defense were common. One such was the crannog (A). Found mainly in Ireland, crannogs were artificial islands built of timber, clay, peat, and brushwood. Dwellings were constructed on top of the island. This crannog, from the La Tene period, is in County Antrim. The most famous Celtic fortifications were the hill-forts (oppida) (B). This hill-fort, seen from the air, is in Somerset.

Figure 4. The god Cernunnos, "The Horned One", figures as the Lord of the Wild Beasts on one of the inner plates of the great votive silver cauldron found at Gundestrup, Jutland, Denmark. He wears the antlers of a stag.

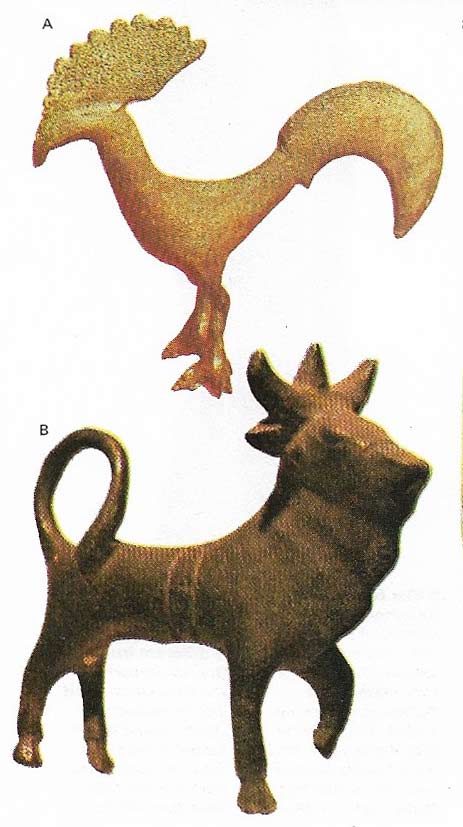

Figure 5. The cock (A) was believed to avert evil with its crow and thus in Britain it was considered unlucky to eat it. The peculiar three horns on the bull (B) conveyed an idea of its supernatural qualities as the number three held religious significance.

Figure 6. An early example of La Tene art style is shown here. The bronze plaque from a double burial at Waldalgesheim (c. 325 BC) shows a mask-like face, a torque round the neck and, on the head, traces of a leaf-crown which is a token of divinity. The hands are raised in the Celtic attitude of prayer. This bronze is one of a pair.

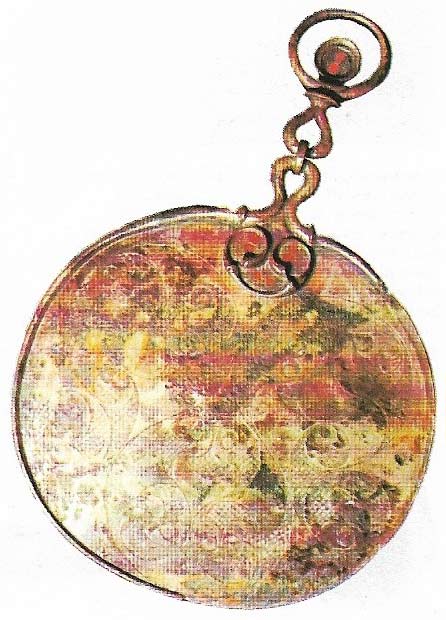

Figure 7. Bronze decorated mirrors are among the most splendid pieces of Celtic art. This example, from a woman's grave at Birdlip, Gloucestershire, is pre-Christian.

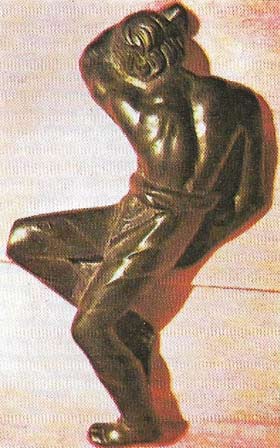

Figure 8. A bronze figure of a dying Gaul was recovered from the hill-fort at Alesia, Alise-Ste-Reine, where Vercingetorix, the young Celtic leader, king and commander of all the Gallic confederates, made his last great stand against Julius Caesar in 52 BC. For a time he man-aged to repulse Caesar and cause him heavy losses, but after a final bitter battle he was defeated. In spite of the dignified and noble way he surrendered in order to save his fellow countrymen, Caesar held him prisoner in Rome for six years and then ordered his belated execution.

From the beginning of the second phase of Celtic culture, known to archeologists as La Tène, our knowledge becomes much more detailed. The archeological record is filled out by written accounts that give a fuller, more detailed identity to peoples previously distinguished by the remaining artefacts of their material culture alone. For the first 500 years of this period of European history, the story is basically that of the astonishing growth and development of the Celtic world and its gradual decline with the rise of Rome and the establishment of the Roman Empire.

The development of Celtic culture

The term La Tène is applied to this period of Celtic culture that extends from about 500 BC and is the period of their greatest attainments. Like Hallstatt for the first phase of c. 700–c. 500 BC, the name La Tène is taken from the name of a major archaeological site. In the nineteenth century a large variety of religious offerings (3) were found at La Tène on the shores of Lake Neuchatel in Switzerland, and these findings, like those discovered at Hallstatt, testify to the changes in the equipment and way of life experienced by the Celts. As with Celts of the Hallstatt culture, their altered lifestyle was developed more or less simultaneously, and with great rapidity, over much of Europe.

|

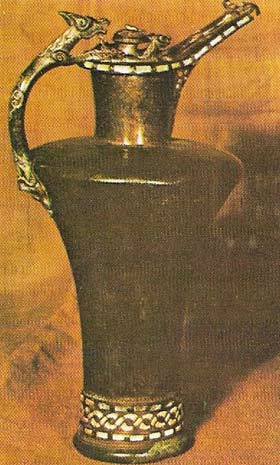

| This bronze wine flagon is one of a pair from Basse-Yutz in Lorraine. Inlaid with coral, it demonstrates elements that contributed to the subtlety and charm of La Tene art. The wolf-like animals forming the handles and on the lid link these pieces with the Bronze Age cult of water birds. |

The Celts were still highly aristocratic in their social organization; kingship was common among the tribes and below the king were the warrior aristocracy and freemen farmers. The Celts had a highly evolved religion (5, 6) with the powerful priesthood – the Druids – which itself formed a major class. In addition there were slaves.

The Celts had taken to using a light two-wheeled war chariot pulled by two small ponies, and the artistic skill of their craftsmen in metalwork, always remarkable, had advanced to new heights. At the same time, a revolution had taken place in their art style. The old Urnfield and Hallstatt patterns, the fine animal art of the Scythians, Greek foliage motifs, and elements from styles formed much farther east had been merged into a brilliantly original art – subtle and elusive, and full of magical significance. From 500 BC this new aspect of Celtic culture spread rapidly and by 300 BC it was dominant from the Baltic to the Mediterranean and from the Black Sea to the Atlantic.

|

| Belief in the 'evil eye' goes far back into Celtic minds. The eye on this stone figure of a boar god dates from about the 1st century BC. |

Celtic society and warfare

The early Celts did not make written records, they recorded their history orally. However, unlike the earlier Hallstatt culture, that of La Tène is nevertheless well documented; much of our knowledge about the daily life of the Celts has been provided by contemporary Greek and Roman writers.

To them the Celts were tall, muscular and fair-skinned, qualities most attributable to the warrior class and reaching their ideal in the gaestatae ("spear-bearers") who were a highly specialized class of Celtic warriors.

Warfare was an essential part of the Celtic life. Armed with highly efficient iron weapons the Celts swept through central Europe in the fourth and third centuries, overcoming their Etruscan neighbors in about 400 BC, sacking Rome in 390 and plundering the shrine at Delphi in 279.

But the Celts were not only warriors. They achieved a high level of material civilization using their mastery of iron-working to open up new land and develop agriculture. Their economy was based on mixed farming – the cultivation of grains and vegetables, and cattle raising – and on trade. These two aspects –expansionist warfare and domestic settlement – can best be seen in their hill forts (oppida), the remains of which are scattered throughout Europe. Originally built as hilltop forts for defense only they varied considerably in size, some developing into major towns. One such was the oppidum at Bibracte near Autun in France which covered more than 130 hectares (330 acres) and had houses, streets and possibly shops.

The rise of the Roman Empire

It was the rise of Rome – a little town on the bank of the Tiber – into a great, organized civilization which, by 225 BC and after bitter fighting, defeated the Celts at Telamon in Italy, and took the first major step towards subduing them forever. Even after actual subjugation, the Celtic traditions and language continued to survive but in forms modified to agree with the needs of Roman

institutions. Only Ireland and much of Scotland escaped Roman domination in the British Isles. It was there that the old Celtic traditions and. way of life survived and were written down by the scribes of a Celtic Church, of the 5th century AD and deeply sympathetic to the heritage of its people.

The Roman Empire lasted into the fifth century. But from the third century it was endangered by increasingly powerful "barbarians". It was these barbarians from the north, east of the Rhine and from the vast steppe-lands of the eastern continent who, during the 5th century AD, eventually wrecked the Roman Empire and laid the foundations of feudal Europe. The people of the Roman Empire had become used to living in towns and obeying a single, absolute government. The barbarians knew no such control, living in tribes without towns and led by chieftains who gained their power through the dictates of tribal custom and tradition. These pagan peoples struck deeply at the growing Christian Church in Europe, a Church to which Celtic missionaries from Ireland were to contribute profoundly.