Charlemagne and the Carolingian Empire

Figure 1. A battle of crucial importance for the future at Poitiers in 732 when Charles Martel and the Franks finally put a stop to the advance of the Arabs, who threatened to destroy the Christian West completely. The Franks had already been successful in defeating the German tribes east of the Rhine. Frankish expansion under Charlemagne was therefore based on 300 years of Frankish strength.

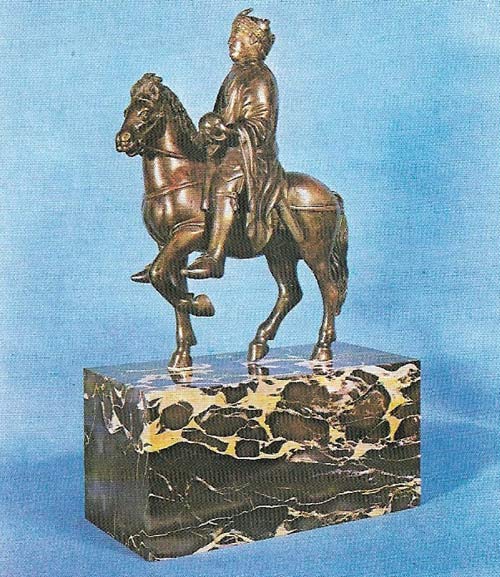

Figure 2. Charlemagne's military leadership was the basis of his power. Frankish custom, based on a tribal levy, made every freeman liable for military service and for equipping and feeding himself at war. Later, middle class freshmen gave up their lands to local lords and fought in the lords' retinues, saving the small man expense but destroying the unity of the Frankish army on which Charlemagne had built his power.

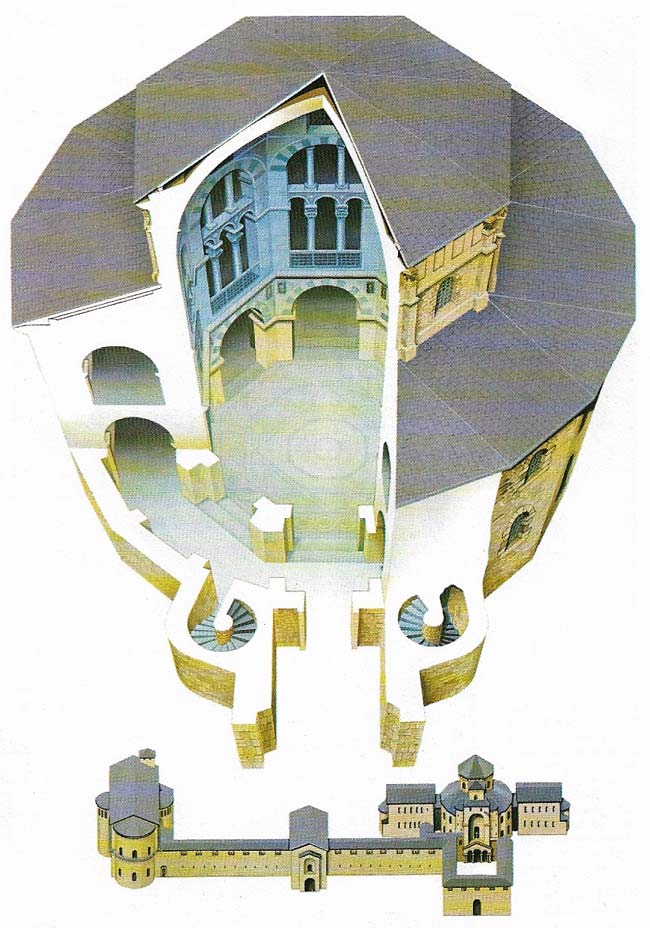

Figure 3. Charlemagne's Palace Chapel at Aachen was the architectural masterpiece of Carolingian Europe and a symbol of imperial power. It was based on the design of St Vitale in Ravenna, capital of the empire in Italy after the fall of Rome, and was designed as a chapel to house Charlemagne's throne.

Figure 4. The Lothar Crystal, a solid piece of rock crystal delicately engraved with biblical scenes, made in the 9th century, was owned by Lothair II of Lorraine (r. 855–869). The quality of the carving demonstrates the continuing artistic achievements of the Carolingian Empire despite the political decline of the 9th century. The classical motifs show how Rome was being used as an example by the Franks.

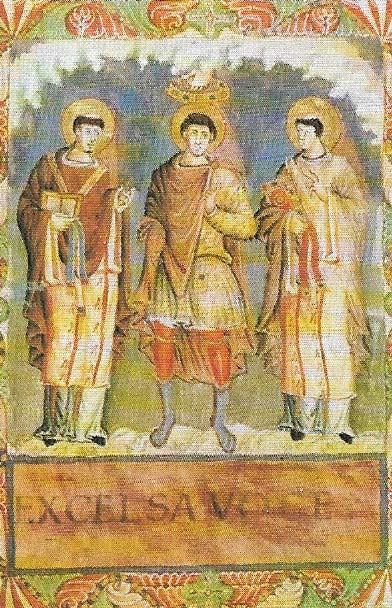

Figure 5. This page from the Sacramentary of Charles the Bald (823–877) shows the coronation of a Frankish prince – possibly Charles himself. He is flanked by two clerics and appears to be being crowned by God in person, handing a crown down from heaven; the Church's role in supporting the throne and the royal sense of divine mission are thus illustrated together. The Sacramentary was written and illustrated in 869–870 and saw the height of achievement of the last great school of Carolingian illumination which had developed around the Court School at Aachen and spread to Reims and Tours before it reached St Denis.

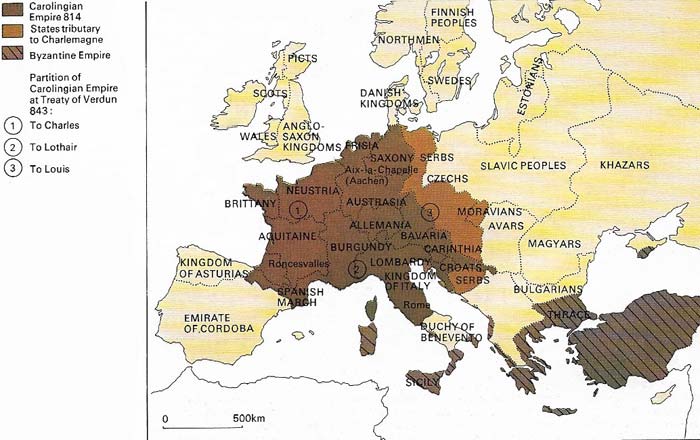

Figure 6. The size of Charlemagne's empire on his death in 814 makes a sharp contrast with the partitions ratified at Verdun in 843 after 30 years of squabbling among his successors. The poet Theodulf wrote: "The wall, so firm and artistically decorated in the days of my youth is showing cracks... Everything sweet has fled from the aging world and nothing is left of its former strength."

The Carolingians, a dynasty named after Charles Martel ("the Hammer") and his grandson Charlemagne, became the leading aristocratic family among the Franks in the 7th century. The family's power and prestige were greatly increased during the rule of Charles Martel (c. 688–741) who united the Frankish kingdom, halted the advance of the Arabs at the Battle of Poitiers in 732 (Figure 1)and began a political relationship with the Papacy that led to the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire. Charles Martel's son Pepin (c. 715–768), the father of Charlemagne, ruled from 747 and was anointed king with papal approval in 754. In 753 Pope Stephen sought the aid of the Franks against the Lombards who, having taken Italy, were threatening Rome. The king of the Franks became a regular ally of the pope, and the Carolingian house was invited to divide Italy with the Papacy.

The Frankish dynasty

The Franks traditionally considered their kings as being of divine origin and saw the tribe as the possession of its royal family. The Frankish state as such only existed under strong kings such as Clovis (465–511) and Pepin who eliminated their rivals. On Pepin's death his sons Charlemagne (742–814) and Carloman succeeded. When Carloman died in 771 Charlemagne seized full control. In 773 he answered the Papacy's call and defeated the Lombards. From 774 he ruled Italy by conquest and swore an oath of assistance with the pope.

|

| Charlemagne was the most powerful ruler in medieval Europe. Standing 193 centimeters (6 feet 3.5 inches) tall with broad shoulders, he was physically impressive. His character was enigmatic and his personal religion erratic, although he oversaw the consolidation of Christianity throughout his realm. He was politically ambitious, appointed able ministers, and understood the importance of education. He unified Western Europe and recreated an equivalent of the old Roman Empire. But he regarded his lands as private property and willed them to his sons. It is hard to know whether he saw himself as an international leader or simply an unusually successful Frankish tribal chief. |

The reign of Charlemagne

The Papacy was now as frightened of the Franks as it had been of the Lombards and sought a way of restraining Charlemagne. The solution came in 800 when Leo III crowned Charlemagne, initiating the Holy Roman Empire and giving rise to the claim that the emperor held his power from God bestowed upon him by the pope.

|

| The coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in St Peter's on Christmas Day 800 was depicted in a 15th-century miniature by Jean Fouquet. Charlemagne, who had just restored Rome to the pope after a revolt, needed a sacred seal on his de facto position as emperor. The coronation made him legally heir to the Western Roman emperors. It was more the culmination of Carolingian expansion than an expression of a papal claim to select temporal rule. |

Charlemagne was a warrior king. Wars were fought against the Lombards in Italy and against the Agilolfing dukes of Bavaria; in addition there was a constant succession of campaigns against the barbarians on the borders of the kingdom: Arabs, Avars, Slavs, Saxons and Danes. War was carried out not only for political reasons but also for plunder. Charlemagne was often poor in the early years of his reign and a Frankish king's power rested on his ability to reward his followers. Booty taken in war was his single most important revenue.

Charlemagne fought the Arabs in Spain in 778, a campaign that ended in the ignominious defeat of Count Roland at Roncesvalles at the hands of the Basques. In the south he defeated the Lombards and overthrew Tassilo of Bavaria in 788, making Bavaria for the first time an integral part of the Frankish Empire (Figure 6). From 772 to 804 he waged a bloody and almost continual war against the Saxons, led until 785 by Widukind, and he proceeded to conquer Bohemia in 805–806.

|

| The death of Roland at the Battle of Roncesvalles in 778 gave rise to one of the great epic poems, the Song of Roland. It epitomized Charlemagne's knights as chivalrous defenders of Christianity against the Saracens. In literature, as in politics, the Carolingians thus laid a foundation of medieval lore. On his immediate retreat across the Pyrenees to put down a Saxon rising in the north, the rearguard of his army was in fact annihilated by a Basque force at Roncesvalles. |

Charlemagne's military prowess recreated a centralized European government that needed an administration more complex than any known to the Franks. Charlemagne created a new court at Aachen (Figure 3), with a palace and cathedral built on an imperial model. He employed a circle of scholars, including Alcuin from Northumbria and Theodulf from Spain, to educate a new literate class of administrator, to produce a new and legible script, to reform the practice and liturgy of the Church and to produce a theory of empire to accompany the reality of imperial power. Alcuin, above all, formulated the role and responsibilities of the Christian emperor, thus justifying the imperial side of the relationship with the Papacy.

Organization of Frankish society

Charlemagne ruled his lands through local counts, of whom there were more than 200. Many were of royal blood, and their appointment by Charlemagne created the beginnings of an international aristocracy that long outlived the Carolingian Empire. He employed stewards to carry out the business of government and special travelling agents, the missi dominici, to keep the counts in line with imperial policy and to raise troops when necessary. The royal will was expressed in a series of imperial charters that were lucid and authoritative. The Church played a central role in administration both through the services of educated bishops and clerics and the unification of doctrine and practice.

Frankish society had earlier been based solely on personal loyalty to the king. Gradually Charlemagne insisted on a new oath of fidelity, initially only in times of crisis. These oaths were the beginning of a feudal monarchy based on the sworn allegiance of a landed nobility, a completely different concept from the personal loyalty of a tribe to its chief, for example.

Charlemagne intended to leave his empire divided between his sons, but Louis' reign, which began in 814, was a chapter of bitter family rivalry and the Church was increasing its control over secular affairs. A new wave of external attack from the Arabs, Bretons, Vikings and Normans further weakened the empire. Louis died in 840 and after three more years of feuding the Treaty of Verdun divided the empire in three. Carolingian rule had disintegrated by the end of the ninth century but Europe had been given an imperial ideal, an international landed aristocracy and a series of significant social bonds that were soon to be revitalized.