China 618 to 1368

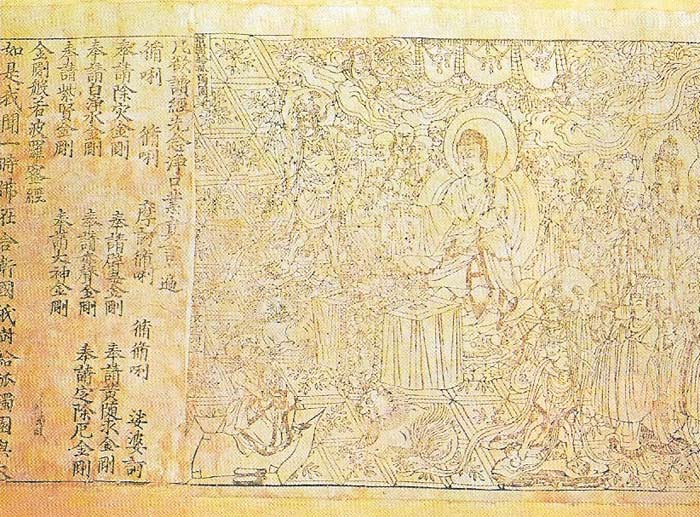

Figure 1. The Diamond Sutra, the world's oldest printed book, dates from AD 868, nearly six centuries before the first printing in Europe. With gunpowder and the magnetic compass, printing was one of the revolutionary inventions developed by China long before the west. The consequent growth in literacy meant that increasingly the civil service (for which, in theory, recruiting had always been democratic) was drawn from a wider circle of families. Printing facilitated the great expansion of the economy that characterized the Sung dynasty by making possible the introduction of paper money and credit notes.

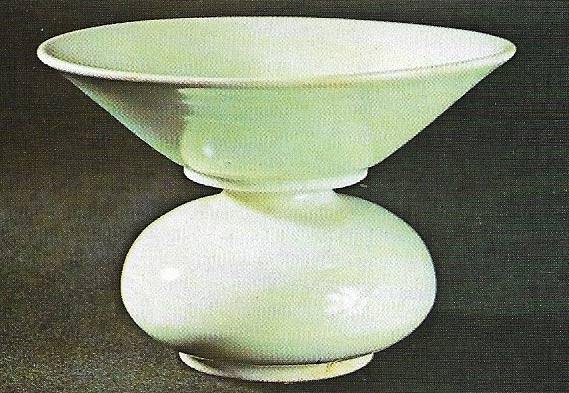

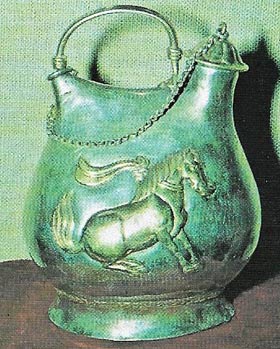

Figure 2. A fine example of the elegant work that was produced in the classical period of Chinese civilization is this white T'ang porcelain spittoon of the late 9th century. It comes from Hsing-Chou in the modern province of Hopei and exemplifies the best of the high-fired ceramic ware produced there. Under the T'ang, Ch'ang-an was a thriving capital, one of the cultural centers of the East. Its wealth came partly from the prosperous western trade – Chinese goods were much in demand along the Silk Route. The T'ang is often seen as the artistic complement to the great scientific and technological achievements of the preceding Sui dynasty: the T'ang literary achievement in prose, as in verse, remains unsurpassed.

Figure 3. Maritime commerce expanded greatly during the Sung dynasty. Sea-going junks, such as the porcelain model here, carried cargoes of silk and porcelain to the East Indies, India and the east coast of Africa. Undoubtedly improvements in navigation (which was greatly aided by the invention of the floating compass in AD 1021) contributed to these ambitious trading expeditions.

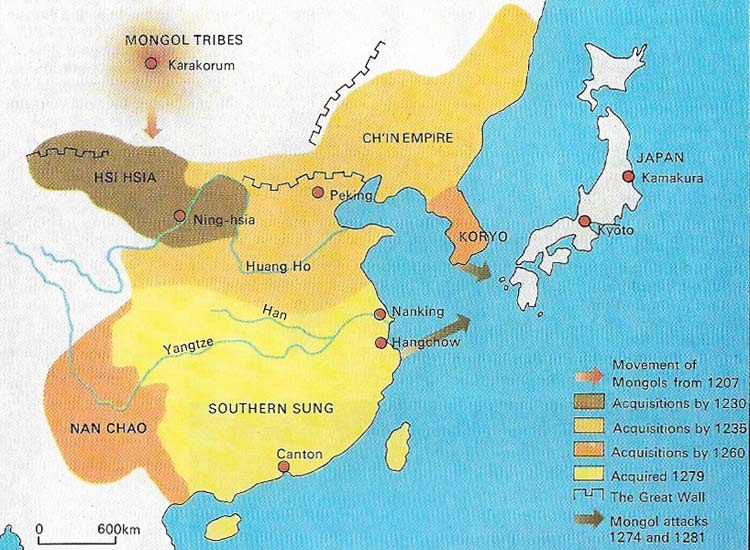

Figure 4. The Mongol conquest of China was finally completed in 1279. The Sung had previously allied with the Mongols against the Ch'in in the north but were eventually encircled by Mongol conquest.

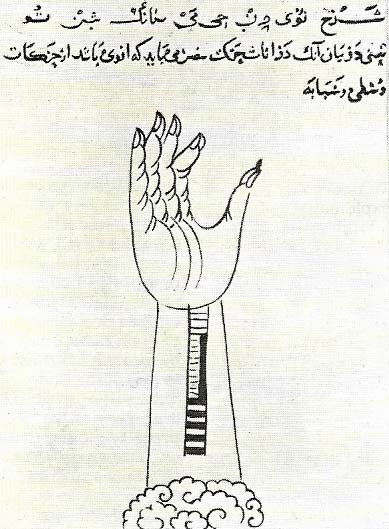

Figure 5. This medical drawing from a Persian textbook of the 14th century is in fact of Chinese origin and shows the widespread influence of Chinese science.

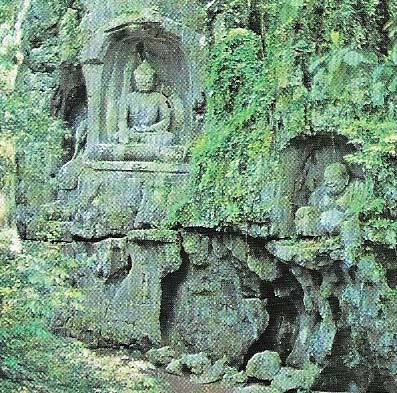

Figure 6. Buddhist temples carved from rock caves were features of the Yun-kang and Lung-men periods (in the 5th and 6th centuries AD). The last of them (like the Fen-lai-feng cave temple near Hangchow, of which a detail is shown) were carved in the late century (in the Yuan dynasty). Buddhism in China reached its peak in the middle of the T'ang dynasty, but thereafter the faith was gradually absorbed into traditional Chinese customs and philosophical beliefs.

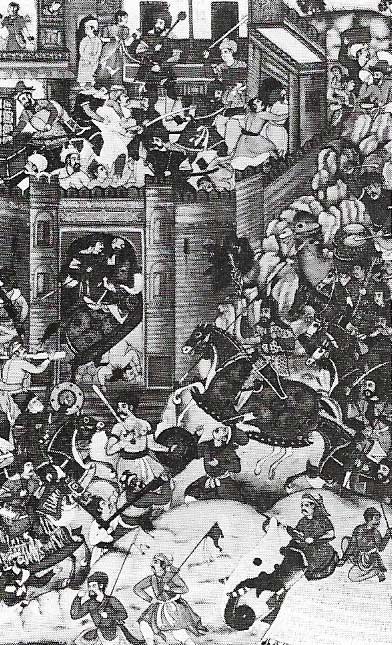

Figure 7. Genghis Khan's army capturing a Chinese town is recorded in this painting. The Mongols came to rule almost all of Eastern Asia as part of an empire stretching across Asia to Hungary and the Black Sea. After the conquest of the Sung in the south, China was for the first time ruled by foreign invaders. The Chinese-style Yuan dynasty ruled China for less than 100 years. Under the Mongols trade routes across Asia were safeguarded and a variety of religions, including Christianity, were permitted. Kublai Khan was the first Yuan emperor, but after his death Mongol rule was short-lived, ending in a series of rebellions and, finally, expulsion.

Figure 8. The abacus, introduced during the Sung dynasty, is still widely used today in all areas of commerce. Under the T'ang and Sung the economy underwent a rapid expansion, similar to that which occurred in 17th century Europe, but despite this Chinese society remained essentially feudal.

The Emperor Li Yuan, who founded the T'ang dynasty (618–907), was followed by his son, the Emperor T'ai Tsung (reigned 627–649) under whose rule China became the most powerful and the largest empire on Earth. The security China enjoyed in this position encouraged trade with the outside world and brought in a rich horde of goods. The trade also carried scientific ideas westward beyond the borders of China (Figure 5).

Art, commerce and religion

Chinese arts flourished during the T'ang dynasty (Figure 2) particularly poetry, and it produced such poets as Wang Wei, Li Po and Tu Fu. The earliest known printing commenced in this fruitful period and paper money was first issued (Figure 1). Money-lenders thrived in the numerous markets and the growth of commerce brought prosperous trade with merchants from Japan, Central Asia, Arabia, Turkey and the Mediterranean.

|

| This silver wine flask of the T'ang dynasty is a typical piece of Chinese metalwork displaying strong foreign influence. Under this dynasty the capital, Ch'ang-an (now Peking), was probably the most cosmopolitan city in the world and as the empire expanded, merchandise arrived from all quarters. The flask is modelled on the leather water bottle widely used by travelling merchants. |

The emperor was as tolerant of the religions that the foreigners introduced as he was of the merchants themselves. Although a Taoist, he supported Confucianism for reasons of state and treated Buddhists with great respect. Zoroastrian temples and Nestorian Christian churches also existed in the capitol Ch'ang-an, modern day Peking.

Wu Tse-t'ien – an efficient empress

The peace and prosperity that T'ai Tsung brought to the empire was continued by his former concubine, Wu Tse-t'ien, who came to the throne in 683 and ruled China with ruthless ability until she was forced to abdicate in 705 at the age of 82. She was a profound believer in Buddhism and was the first and only female "Son of Heaven". Much of the progress and stability of the country was due to the fact that civil service officials were selected by examinations held under controlled procedures. The empress also permitted women to sit the examinations for government posts.

|

| This T'ang mandarin was one of the highly educated, privileged and wealthy elite who comprised the mandarinate or civil service. The continuity and resilience of the large state bureaucracy from earliest times is one of the more remarkable features of Chinese history. Its officials, selected by public examination, collected taxes, supervised state projects and nationalized salt and iron industries (under state control since the Han dynasty) and administered local areas. They also supervised the merchant communities and foreign trade, a despised business largely in the hands of immigrants, but strictly controlled by the state. |

The main function of the government was the collection of revenue and the promotion of the agriculture on which it mainly depended. For this purpose the country was divided into districts controlled by magistrates. The people were divided into three groups mutually responsible for each other's conduct and for tax payments – encouraging a sense of collective responsibility that is still a feature of China today.

T'ang influence spread far afield, to such an extent that the Japanese capital of Nara was modelled on Ch'ang-an. In the west it clashed with Islam. Muslim armies had advanced, bringing their faith as far as Samarkand and Bokhara. Eventually they conquered Central Asia, severing the overland route between China and the West. Trading continued by sea, but the power of China began to wane and as it weakened she became less tolerant of foreigners and their religions. In 845 all foreign religions were proscribed and a ban was placed on Buddhists and their rich but unproductive monasteries (Fig 6). Disastrous revolts and invasions decimated the population and in 907 the T'ang dynasty ended in ruins.

Five dynasties and the Mongols

The T'ang dynasty was followed by a period called the Five Dynasties between 907 and 960, when, as a Chinese poet said, "States rose and fell as candles gutter in the wind". In 960 the Sung dynasty was founded by Chao Kuang-Yin. The war-weary country was at last glad to accept established rule and welcomed the new emperor, who took the title Sung T'ai Tsu. China was still threatened from the north and in 1044 an indemnified peace treaty was concluded with the Hsia, a former tributary kingdom. Gunpowder, which had been discovered during the T'ang period but had been used only for fireworks, was now used to produce the first military rockets in history.

|

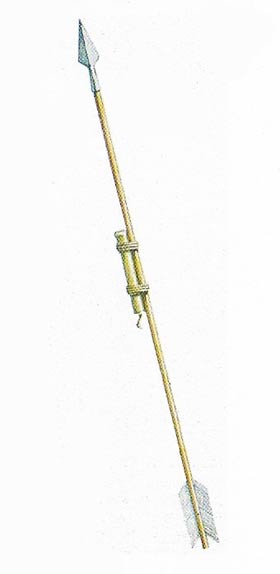

| Gunpowder was discovered by Taoist alchemists in about the 9th century and was used strictly peacefully. By AD 1000 simple bombs, grenades and rockets were being made, but it was the Mongols who first exploited gunpowder for military ends. They probably used a type of cannon in their campaigns against the Sung troops and certainly employed Chinese engineers. The Mongols captured the Sung fleet which was armed with trebuchets for firing bombs. Although gunpowder was a Chinese invention, it did not have the revolutionary effects on Chinese society that it had in Europe. Illustrated is a Chinese rocket of the Sung dynasty. |

The loss of the northern part of the country was partly offset by sea trade, which had been considerably helped by the Chinese discovery of the compass. Large ocean-going junks (Figure 3) carried cargoes of tea, silk, porcelain, paintings and other works of art to the East Indies, Africa and India. Another important invention was the abacus (Figure 8), the first calculating machine and one still widely used.

The Sung dynasty ended a similar manner to the previous empires. Corruption at court and discontent among the people permitted the ascendancy of the latest nomad empire of the north, the Mongol nation. The new invasion started in the 13th century when Genghis Khan (1167–1227) invaded northern China (Figure 4). By 1223 he had conquered most of the country north of the Yellow River and defeated the Hsia, killing about 90 percent of the population (Figure 7). However, it was not until 1264 that his grandson Kublai Khan (1215–1294) was able to move his capital from Karakorum in Mongolia to Peking, and, in 1279 he overcame his former allies the southern Sung.

Mongol rule or, as it was officially known, the Yuan dynasty (1264–1368), was successful in uniting the Chinese and Mongol empires and under Kublai Khan Mongol power reached its peak. But the invaders were eventually overcome. Kublai Khan's successors did not have his ability and the oppression of the Chinese by hordes of foreign officials led to the formation of secret societies and to revolts. In 1356 Nanking fell to a peasant movement led by a monk. Chu Yuan Chang, who finally became first emperor of the new and purely Chines d, the Ming, in 1368.