East Asia 1919 to 1945

Figure 1. The May 4th Incident in 1919 was a demonstration by 3,000 students in Peking, protesting at the Paris Peace Conference that left Japan in control of German possessions it had seized in China. Spreading protest forced government changes and foreshadowed a new Chinese nationalism.

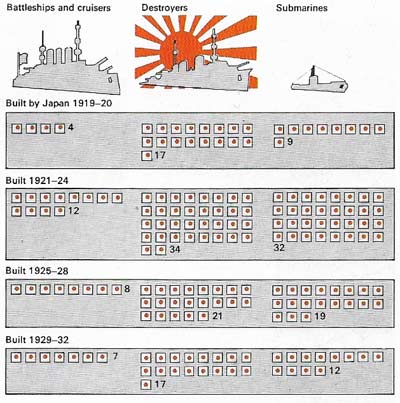

Figure 2. Japanese naval power grew rapidly in east Asia after 1919 despite the 1922 Naval Treaty limiting replacement of capital ships by the US, Britain, and Japan to a 5:5:3 ratio. Ratios for auxiliary ships set in 1930 were: heavy cruisers 10:10:6; light cruisers and destroyers 10:10:6; submarines, parity.

Figure 3. Communists were massacred in Shanghai on 12 April 1927 were Nationalist troops, police and secret agents, disarmed workers and pickets, and dissolved labor unions. The culmination of a power struggle between the left and right wings of the KMT, the purge spread elsewhere with more massacres of the Chinese left-wing and communists.

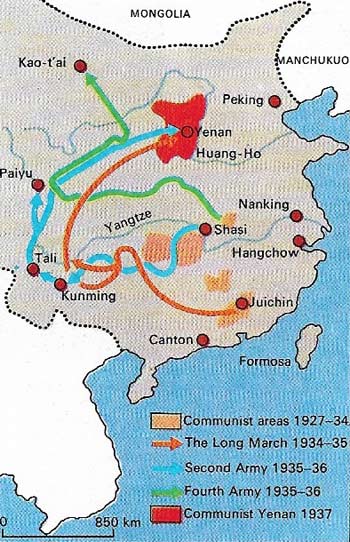

Figure 4. In the Long March, about 85,000 communist soldiers and 15,000 officials left Kiangsi province under pressure from Chiangmai Kai-shek, in 1934. A year later 30,000 survivors regrouped near Yenan after a March of 8,000 kiilometers (5,000 miles). The communist 2nd and 4th armies also had to regroup in the north.

Figure 5.The fall of Nanking, Chiang Kai-shek's capital, on 12 December 1937, was followed by the massacre of some 100,000 people by Japanese troops. Known as the "rape of Nanking", this atrocity was revealed at the International War Crimes Tribunal in Tokyo. The city's fall came after three months of stubborn opposition by Chiang's army to the advance of the Japanese.

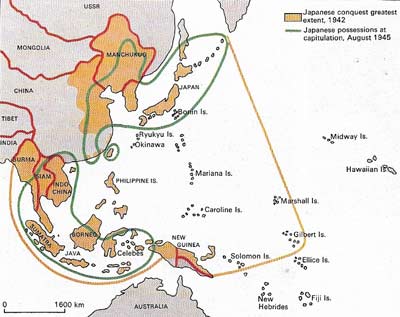

Figure 6. Japan's territorial acquisitions in World War II reflect its initial aims: to conquer China before dealing with the USSR and to control the southwest Pacific. Later of the military priority shifted to include invading India in preference to defending Pacific islands. Before the Allies entered the war against Japan, China traded space for time. Once deep in Chinese territory, Japanese troops, although controlling most industrial areas, were surrounded by a hostile countryside.

Figure 7. Japan's surrender was signed aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945 with General Douglas MacArthur representing the Allies. The Japanese decision to surrender on 14 August 1945 came from the Emperor.

Figure 8. Chiang Kai-Shek (1887-1975) was the leading military aid of Sun Yat-sen by 1919. After Sun's death in 1925 he dominated the Kuomingtang and became president of a largely reunited Republic of China in 1928 but his authority was contested by the Communist Party and threatened by the Japanese. Recognized by the Allies as China's wartime leader, he secured the abolition of extraterritorial rights in China in 1943 and in 1945 a seat for China in the UN Security Council. Renewed postwar conflict with the Communists led to his defeat and the withdrawal of his government to Formosa (now Taiwan) in 1949.

The history of East Asia from 1919 to 1945 is dominated by two related themes: the rise of Chinese nationalism in the 1920s and the spread of Japanese imperialism after 1931. Both developments were influenced by Western imperialist presence in the region. Chinese nationalism was complicated by the diverging interests of the two major political parties, the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Rise of Chinese nationalism

The year 1919 is a watershed in Chinese history. Demonstrations against the Paris Peace Conference's granting of former German concessions in China to Japan – which the Chinese government accepted – developed into an unprecedented national movement (Figure 1). Sensing the revolutionary mood, Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925) reorganized his Nationalist Party into the disciplined KMT. With both a socialist ideology and a party-dominated army under Chiang Kai-shek (Fig 8), the KMT received help from the Comintern and collaborated with the fledgling CCP formed in 1921. Both parties sought to end the division of China and its exploitation by foreign powers.

These privileges were little diminished by the Washington Conference (1921–1922) which achieved only partial withdrawal by Japan. Chinese dissatisfaction coalesced with labor unrest, particularly in the treaty ports, culminating in a 15-month strike and boycott of foreign trade in Hong Kong in 1925–1926. Against this background, Chiang Kai-shek led a northern expedition to unite China under the National Government set up in Canton. In 1927 Chiang clashed with party leftists, especially the communist bloc within the KMT. Purging the areas under his control (Figur 3), he succeeded in reunifying the KMT at the expense of the left and the CCP, setting up his own government in Nanking and bringing Peking and much of China under his control in 1928.

By 1930 extension of Nationalist authority put Chinese nationalism and Japanese imperialism on a collision course. Japanese privileges secured in Manchuria since 1905 were threatened by China's reassertion of its sovereignty there. Not only was Manchuria a buffer against Soviet ideology and military power, it also represented a considerable economic investment and had a million Japanese subjects.

Japanese imperialist expansion

Japan of the 1920s was characterized by paternalistic capitalism with limited democracy at home and cooperation with the great powers abroad. But in the 1930s ultra-nationalism and militarism fostered ideas of an autonomous economic empire as an answer to the Depression, which had exacerbated tensions in Japanese society. As confidence in politicians waned, popular support grew for the militarists who were close to Emperor Hirohito. Japanese officers in Manchuria used the Mukden Incident of 1931 to create a situation that led to the establishment of a Japanese puppet state, Manchukuo, in 1932. Expansion southward in 1935–1936 was designed partly to create a subservient North China to protect Japan's rear in the event of war with the USSR.

|

| Japanese troops marched into Manchuria after the Mukden incident of 18 September 1931. Acting without the authority of their government, Japanese forces occupied Mukden using the pretext of a bomb on the Japanese-run South Manchurian railway in a skirmish with Chinese patrols. The speedy occupation of Manchuria (shown here) followed. |

|

| Emperor Hirohito (1901-1989) came to the Japanese throne in 1926, having been named regent in 1921. Under the Meiji constitution his position was both sacred and sovereign, although there is little evidence to show the part actually played by the emperor in Japanese policies. |

Japan's encroachment brought a temporary truce between the KMT and CCP in 1936. Chiang had dislodged the communists from their southern rural bases and forced them to undertake the Long March (Figure 4). But the CCP leader, Mao Tse-tung (1893–1976), urged on by Russia, now sought a united front against Japan and Chiang was forced to agree. When full-scale fighting broke out in 1937, the powerful Japanese army forced the KMT to retreat to Changking in the southwest. The fall of Nanking in December (Figur 5) was followed in 1938 by the announcement of Japan's "New Order" with Japanese army rule in occupied parts of China and a puppet government in Nanking (1940).

Japan's empire in World War II

To secure access to Southeast Asian raw materials and to block Western aid for Chiang, Japanese troops entered Indochina in 1940 and moved southward in 1941. America, Britain and Holland responded with a near total embargo on exports to Japan in July 1941, reducing oil supplies by 90 percent. Japan soon put into operation its contingency plan to achieve economic self-sufficiency by force. Allied to Germany and Italy, and envisaging the imminent collapse of Britain and China, it tried to eliminate American interference by sinking the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

By August 1942 Japan had seized a vast oceanic and continental empire (Figure 6). It was not until early in 1944 that Allied sea power reversed these successes. While the Chinese Nationalists and communists tied down large numbers of Japanese troops in a war of attrition and Allied supply lines were restored in Burma, American amphibious offensives in the Philippines and Gilberts established bases from which air power could be brought to bear on Japan itself. In 1945, after atomic bombs had destroyed Hiroshima (6 August) and Nagasaki (9 August), Japan agreed to unconditional surrender on 2 September (Figure 7).

Japan's defeat left China divided between a Nationalistic administration gravely weakened by the war and the communists who had gained in strength. Japan was transformed under American occupation into a democratic state. In east and southeast Asia, the old empires were never to recover their shattered prestige and power.