Egypt 1570 BC to Alexander the Great

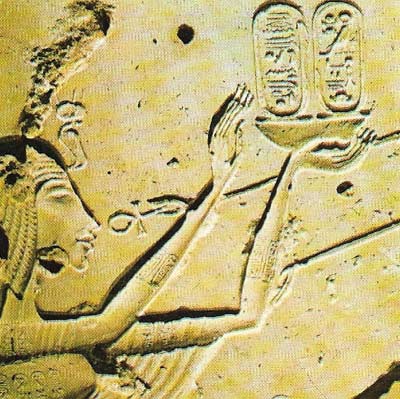

Figure 1. The ancient cult of the sun-god Re had been eclipsed by the rise of the god Amun, until Akhenaton tried to suppress the worship of all gods except Re. The sun-god was represented in the form of the Aton or sun disk, adored here by his queen Nefertiti.

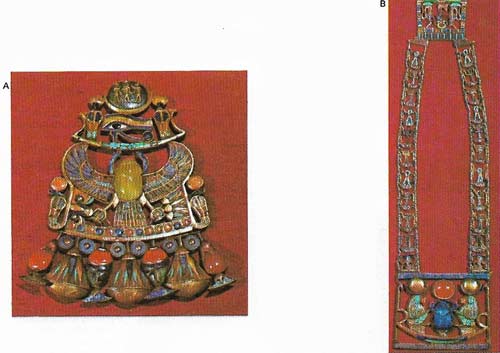

Figure 2. This treasure, a pectoral with solar and lunar emblems (A) and a necklace of the rising sun (B), is from the pyramid tomb of Tutankhamen who succeeded to the throne through his marriage to Akhenaton's daughter and heiress. Bowing to political pressures, he renounced Akhenaton's religion and abandoned Amarna, returning to Thebes and restoring the worship of Amun and other gods. He died c. 1340 BC. His pyramid tomb was the only one left intact. Persistent robberies ended the system of pyramid burials. Instead cliff tombs were cut in the well-guarded Valley of the Kings.

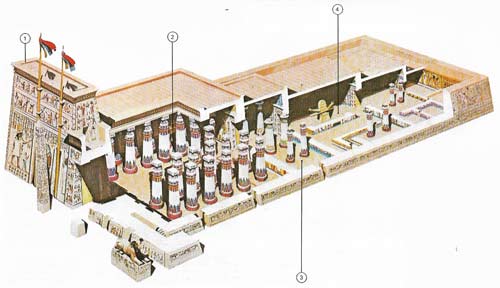

Figure 3. Egyptian temples conformed to a common plan. This can be seen clearly in the small temple of the god Khons within the temple complex at Karnak in Thebes. The entrance to the temple was through a pylon (gateway) (1) into an open court (2) with a colonnade along the sides. Off this, along a straight axis, was a hypostyle (pillared hall) (3) leading to the sanctuary (4) where the image of the god lay. Service and storage rooms surrounded the sanctuary. Because each Egyptian ruler was determined to create an enduring reputation through building works, most major temples were forever being enlarged and remodeled by the addition of more courts and rooms to the existing structure.

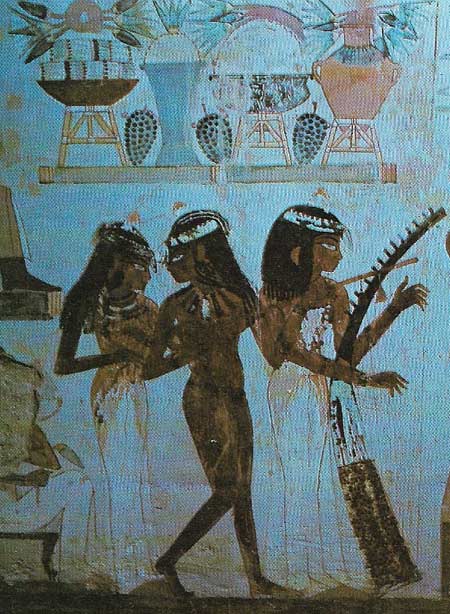

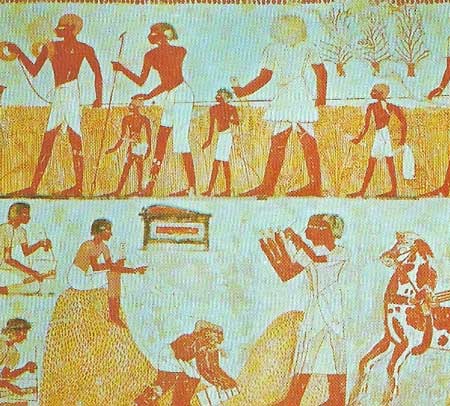

Figure 4. The brilliantly painted tombs of the New Kingdom at Thebes reflect the life led by Egyptians of all classes. It was believed that these scenes could be magically brought to life so that the dead man would not be bereft of his possessions and pleasures on entering the next world.

Figure 5. The economy of Egypt was agrarian, most of the people working on the land. In theory all land was held by the crown but in practice large estates were also held by the official classes and the temples. A limited number of peasant proprietors also owned tracts of agricultural land.

Figure 6. The invasion of the 'Sea-Peoples', including the Philistines and maybe the ancestors of the Sicilians, was repulsed by Ramesses III at the end of the New Kingdom.

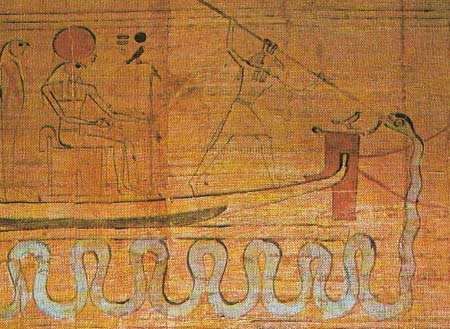

Figure 7. Most tombs in the New Kingdom include a Book of the Dead containing spells intended to guarantee the safe passage of the deceased to the afterlife.

The New Kingdom in Egypt (c. 1570–1085 BC) dates from the victory of Theban forces over the Hyksos rulers of Egypt. New Kingdom Egypt was an empire extending from the northern Sudan to Syria and was one of the major powers of the ancient world. The god of Thebes, Amun, was elevated to the rank of principal deity of the realm and was identified with the sun-god Re in the form Amun-Re, king of the gods (Fig 1). Much of the wealth that flowed into Egypt as a result of its conquests was directed towards the service of Amun and his priesthood.

The consolidation of Egyptian power

The early kings of Dynasty XVIII were primarily engaged in rendering Egypt safe from any further incursions by the Bedouin in the east or the Nubians in the south. After stabilizing the eastern frontier the Egyptian rulers undertook a series of campaigns to conquer the kingdom of Nubia in the south and to seize its gold mines. The lack of male heirs to the throne from the marriage of the ruler, to his full sister led to the increasing importance of the royal heiresses. One such was Hatshepsut (c. 1503–c. 1482 BC), wife and half-sister of Thutmose II, who bore her husband no sons. On his death the child of a concubine, Thutmose III (reigned c. 1504–1450 BC), was placed upon the throne and was presumably destined to marry his half-sister. However, his stepmother Hatshepsut later seized the throne for herself and ruled together with Thutmose III, who was allowed no real power.

On Hatshepsut's death, Thutmose III assumed effective control of the government and immediately embarked on a series of campaigns to subjugate the petty kingdoms in Palestine and most of Syria. He also completed the conquest of Nubia as far as Napata and his immediate successors continued his expansionist policies.

Under Amenhotep III (reigned 1417–1379 BC) the Egyptian court reached the height of its prestige, receiving tribute or trade goods from Syria, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Crete and even Greece. His son Amenhotep IV or Akhenaton (reigned c. 1379–1362 BC) changed the Egyptian religion by his worship of the sun-god in the form of Aton, the sun's disk, and moved the capital to the new city of Akhetaten (Amarna). Akhenaton's policy encountered the opposition of the priesthood of the old gods and led to domestic anarchy and the weakening of Egypt's prestige abroad. His successors abandoned his beliefs and order was finally restored in the reign of Horemheb, the last ruler of the dynasty. Upon Horemheb's death the throne passed to his vizier Ramesses 1 (reigned c. 1320–1318 BC), who founded Dynasty XIX (c. 1320–1200 BC).

Confrontation with the Hittites

The aim of the rulers of this period was to restore Egypt's power and prestige abroad and to confirm Egypt's dominant position in Palestine in the face of the growth of the power of the Hittite Empire. This rivalry led to a major clash in Year 5 of Ramesses II (reigned 1304–1237 BC) at the town of Kadesh, where both the Egyptians and Hittites claimed victory. Peace was eventually concluded between the two combatants in Year 21 and sealed in Year 34 by the marriage of Ramesses II with a Hittite princess. His successors were faced with increasing threats from Libyan tribesmen and piratical "Sea-Peoples", but these threats were contained by Ramesses III, (reigned c. 1198–1166 BC) of Dynasty XX (Figure 6).

|

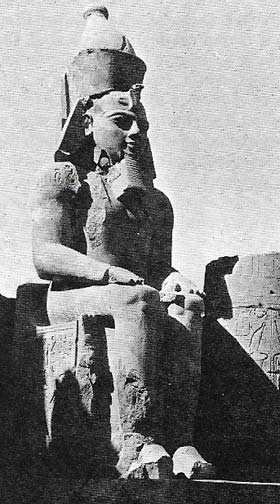

| Ramesses II ensured that his name would be remembered by his extensive building projects. He added the hypostyle hall to the temple of Amun at Karnak and made additions, including this colossus of himself, to the temple of Luxor. On the west bank at Thebes he built his mortuary temple – the Ramesseum. For his favorite queen, Nofretari, a tomb decorated with superb paintings was constructed in the Valley of the Queens. In Nubia he erected the great temple of Abu Simbel, as well as other temples elsewhere in Egypt. He also constructed the city of Pi-Ramesse, his northern capital, possibly using the labour of Hebrew slaves as mentioned in the Bible. |

Under Ramesses III's successors, who were also all named Ramesses, the power of the crown steadily declined in the face of increased Libyan incursions and the growth in the power of local governors, especially that of the high priest of Amun at Thebes. Egypt's foreign possessions in Palestine and Nubia were lost by the end of the dynasty and Egypt itself fell under the control of foreign rulers. Under Dynasty XXI, which ruled from the northern city of Tanis, Thebes was virtually independent under its high priests. The unity of Egypt was restored by the Libyan general Shoshenk I (reigned c. 935–914 BC), founder of Dynasty XXII. He installed his own son as high priest of Amun and attempted to restore Egypt's position as a great power by embarking on a major campaign in Palestine. Under his successors the unity of the country was broken by civil wars and Egypt was partitioned into city states under independent dynasts, mostly of Libyan origin. An independent kingdom had emerged in Nubia in the south and the Nubian kings conquered Egypt in about 712 BC and founded Dynasty XXV.

Nubian rule was terminated by a series of Assyrian invasions that led to the nomination of the prince of Sais as puppet ruler of Egypt. With the help of Greek mercenaries, Psamtik I (reigned c. 664–610 BC) of Dynasty XXVI managed to impose his authority on the whole country and broke with Assyria.

Defeat by Babylonia and Persia

The rule of Dynasty XXVI (670–525 BC) marked a period of renewed prosperity but Egypt's hopes of restoring her position as a great power were defeated by the Babylonians at the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC. Ultimately in 525 BC Egypt was absorbed by the Persians and although subsequent revolts re-established Egyptian independence briefly between 404 and 343 BC, the Persians reasserted their domination until the arrival of Alexander the Great in 332 BC.