early military aircraft

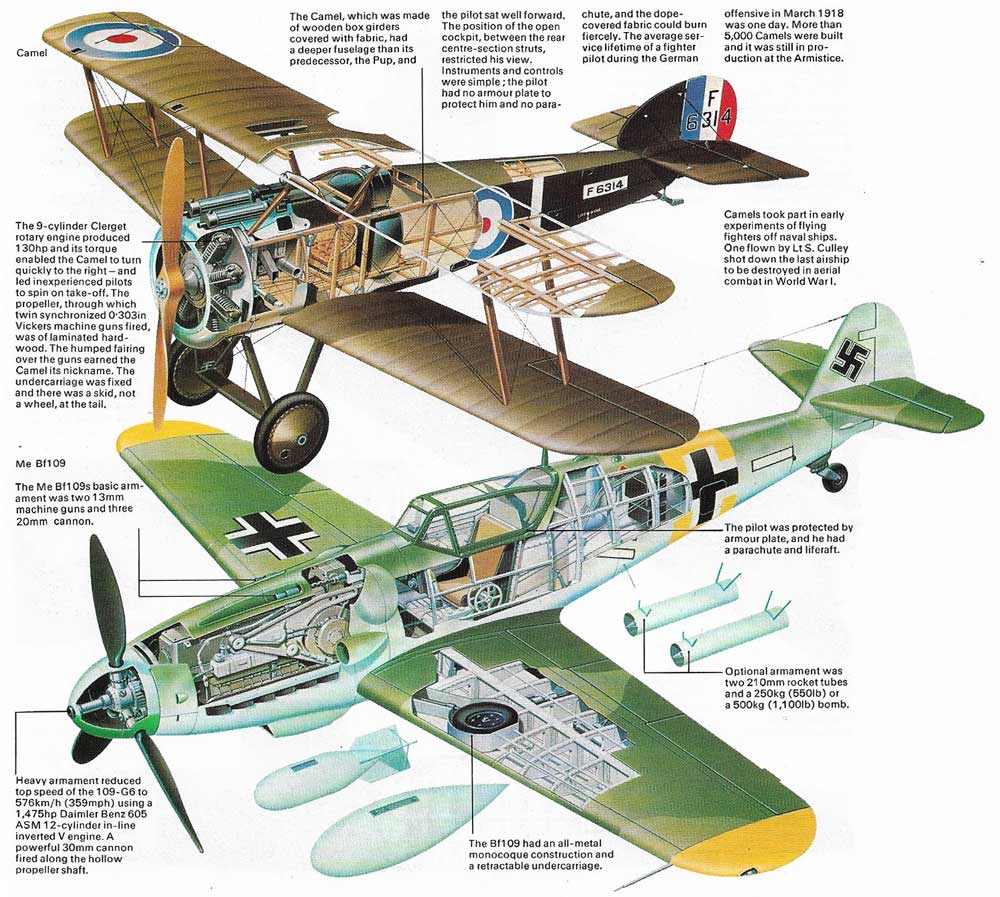

Figure 1. (Top) The Sopwith Camel, a British fighter of World War I, accounted for 1,294 enemy aircraft – a record for any type of aircraft in the war. Its stubby rotary engine gave it a top speed of 182 kilometers per hour (113 mph). In 1918, a Camel, without guns, engine or instruments, cost less than £900. The most expensive engine fitted added about another E900. An interrupter gear prevented the bullets from the two guns hitting the propeller. (Bottom) The Messerschmitt Bf109G was one of the last versions of this renowned German fighter of World War II, which was in production from 1935 in many successively improved versions. Smaller than most Allied fighters, the 109G had a top speed (in the Mk 10 version) of 689 kilometers per hour (428 mph). Its narrow landing gear was unpopular with pilots and the slats to increase wing lift sometimes opened in combat, spoiling the pilot's aim. The cockpit was cramped and at high speed the ailerons, needed to roll the aircraft, were hard to use. But the guns of the Luftwaffe fighters were hard hitting and some Me109s were also equipped with rockets, which could be fired at distant bombers.

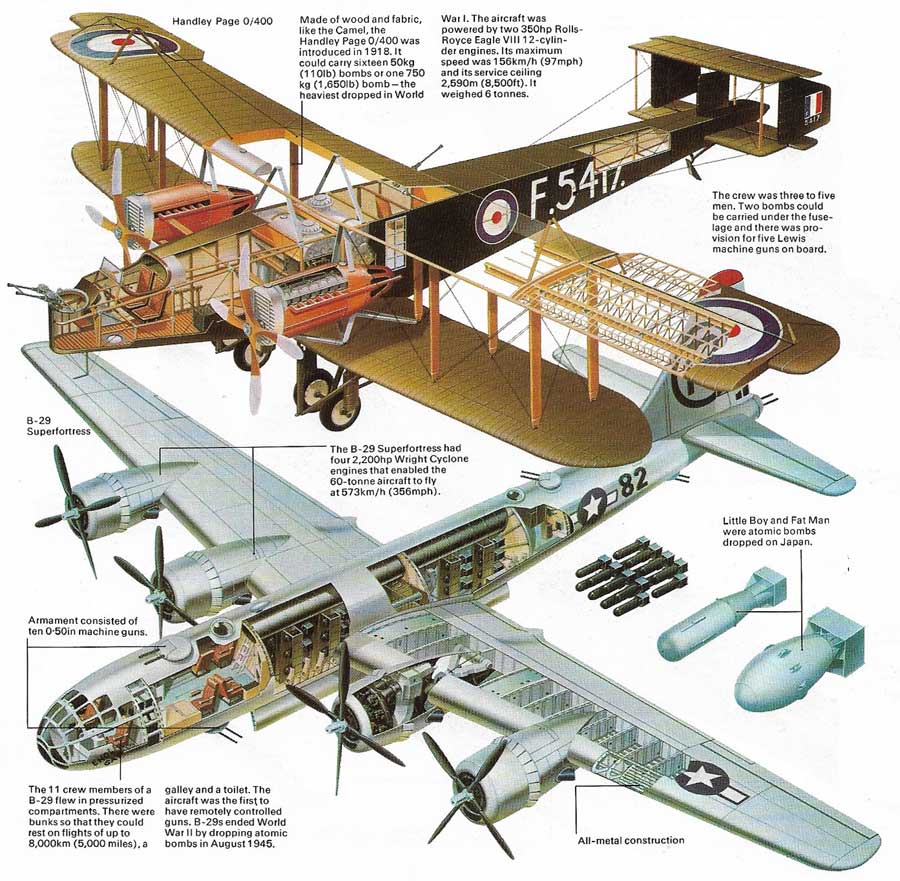

Figure 2. (Top) The best British heavy bomber of World War I was the Handley Page 0/400, originally ordered by the Royal Naval Air Service. Its wings could fold to fit the small canvas hangars of 1918 and it operated from rough grass fields a few hundred meters across. With an endurance of 8 hours, the 0/400 was used against German cities in late 1918. After the war, some 0/400s were used as passenger aircraft. (Bottom) The Boeing B-29 Superfortress was by far the most advanced bomber used in World War ll. First flown in September 1942, it was in action over Japan little more than a year later. Before dropping the atomic bombs that ended the war, B-29s dropped 1,500,000 leaflets on Japanese cities, warning of heavy raids to come. Flying at 10,700 meters (35,000 feet), the B-29 was almost impossible to intercept and it was as fast as most Japanese fighters.

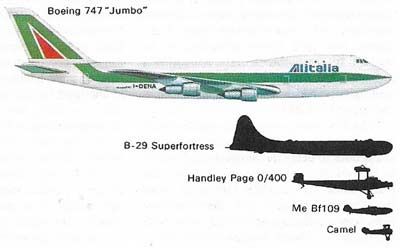

Figure 3. Even the large B-29 Superfortress, the most highly developed of World War II bombers, is dwarfed by a modern Boeing 747 "Jumbo" jet airliner. Yet compared with the Handley Page 0/400 of World War I, the B-29 was nearly four times as fast and could carry 12 times the bomb load. Fighter development was equally dramatic, 1945 aircraft flying up to six times as fast as their World War I predecessors.

An Italian, Lieutenant Gavotti, is credited with dropping the first aerial bomb (on Turks, in Tripolitania, on 1 November 1911) and two Frenchmen, Sergeant Joseph Frantz and Corporal Quenault, with the first victory in aerial combat. On 5 October 1914, a bare 11 years after the first successful flight by the Wright brothers, they shot down a German two-seater with a machine gun mounted on the nose of their Voisin III biplane. The Voisin, with its "pusher" propeller at the rear, offered a clear field of fire forwards.

At the outbreak of World War I, the Germans with 285 aircraft, and the French and British, with a total of 219, were fairly evenly matched. The aircraft were intended mainly for reconnaissance and though some pilots and observers, like Frantz and Quenault, carried weapons, it was not until the first months of 1915 that the air war became serious. In April of that year Roland Garros of the French Air Force fitted steel plates to the propeller of his Morane-Saulnier monoplane. The plates deflected bullets fired through the propeller disk and for two weeks Garros was unbeatable. Then he was forced to land behind German lines. By this time, however, German engineers of the Fokker works had gone a step further and had developed an interrupter gear that synchronized the firing of the gun with the rotation of the propeller. Single-gunned Fokker Eindeckers fitted with the gear created a reign of terror on the Western Front for almost a year. By the summer of 1917 fighters like the Sopwith Camel (Figure 1) had twin synchronized guns.

Specialization

Gradually, as aircraft were made more powerful and reliable, it became possible to design them for specific tasks. Fighters became maneuverable flying guns for attacking other fighters, bombers and ground targets. Reconnaissance machines carried not only an observer but also cameras and radio sets. Bombers grew in size until by the end of the war the newly formed Royal Air Force had bombs that weighed 1,500 kilograms (3,300 pounds) as well as aircraft - the Handley Page V/1500, successor to the 0/400 (Figure 2) – capable of bombing Berlin from airfields in England. Special torpedo carriers were in service, their crews rigorously trained to drop the 800 kilograms (1,764 pounds) "tin fish" at exactly the correct height and speed.

Between the wars

There was little change in aircraft armament between 1918 and 1935. The fighter still carried two machine guns firing ahead through the propeller disk and the bomber was defended by the same two or three men who aimed their machine guns by hand. But there were dramatic changes in aircraft engineering. Engines had to be improved so that they could run not for the 20 or 30 hours that had sufficed in 1918 but for hundreds of hours, without failure. Airframes became both lighter and stronger, the fabric-covered skeleton of spruce or steel tubing gradually giving way to a monocoque (single shell) structure of light metal alloy.

After 1930 the increasing power of engines and ceaseless competition to outfly potential rivals led to the gradual abandonment of the trusty wire-braced biplane, which seldom reached 322 km/h (200 mph). Instead, aircraft became monoplanes. The retractable undercarriage made its appearance – the first military aircraft to have one was the American Grumman FF-1 of 1933 – and guns (up to eight in aircraft like the Spitfire) were located in the wings outside the propeller arc.

The spur of World War II

Engines grew in power from 500 horsepower in 1935 to 1,000 horsepower by 1939 and by 1944 a 2,500-horsepower engine was not uncommon. This meant that aircraft could be heavier and faster. Both Britain and the United States used bombers as strategic weapons. The aircraft were four-engined, carrying up to seven tons of bombs each and defended by power-driven gun turrets. The United States equipped them with turbocharged engines that enabled aircraft like the B-29 Superfortress (Figure 2) to fly as high as 10,700 meters (35,000 feet). German bombers, part of the Blitzkrieg (lightning war), were really close-support tactical machines. Shot out of the British daylight sky in 1940, they took to raiding by night. This spurred the development of large twin-engined night fighters equipped with radar.

Ocean patrol aircraft flew for 24 hours at a time, packed with new systems for detecting surface vessels and even submerged submarines. Reconnaissance aircraft brought back clear photographs taken from heights that ranged from 12,200 meters (40,000 feet) to treetop level. Specially built transports and gliders carried airborne forces and supplies, and naval combat aircraft were developed to operate from aircraft carriers.

By 1945, one or two outstanding machines designed before 1939 still survived in improved forms, the two greatest being the Spitfire and Bf109 (Figure 1). But the way to the future was being shown by dramatically new developments. In 1944 Messerschmitt introduced the bat-like Me163 rocket interceptor and followed this with the formidable Me262 twin jet which could carry four devastating 30-millimeter cannon as well as bombs. Entering service in the same week as the Me262, the British Meteor jet had only 20-millimeter guns, but it was a much safer and more refined aircraft which began its combat career by destroying Vi flying bombs speeding towards London – the first operational missiles.