fighting ships in the age of sail

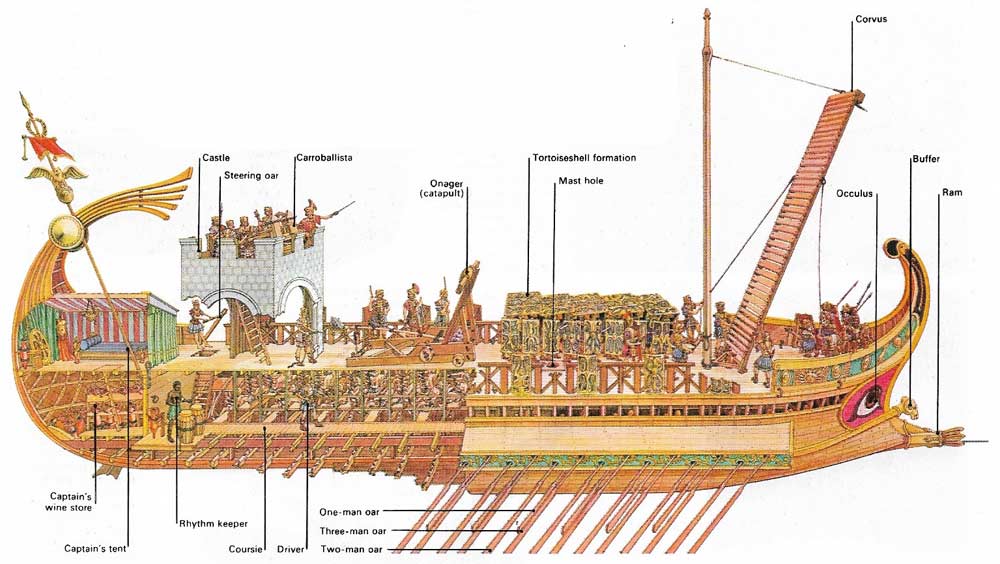

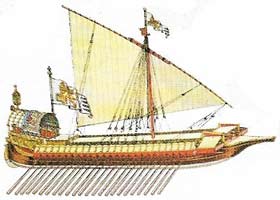

Figure 1. A Roman war trireme of the first century BC can be drawn quite accurately from reliefs of the time. It was propelled either by three banks of oars or by a square sail, the mast being taken out (as shown) before battle. The lower-bank oars were manned by one slave each, the middle by two, and the upper by three. This galley needed 144 rowers. Armament comprised a ram, a drawbridge (corvus) for boarding, a catapult (onager), and a carroballista which fired arrows and blazing darts. The buffer above the ram prevented the galley ramming too far into an enemy ship. The castle was a vantage point for the commander as well as a refuge I battle. On galleys which did not have a castle, there was an elaborate throne placed under an awning for shade.

Figure 2. The Elizabethan galleon (c. 1585) was a forerunner of the ship of the line. The fourth mast disappeared in about 1625, but some 19th-century vessels had four.

Figure 3. The Napoleonic frigate (c. 1800) was a small, single-deck ship used as a fleet auxiliary for its speed and versatility.

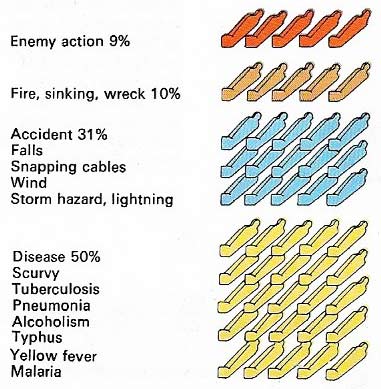

Figure 4. Deaths at sea during the age of fighting sail were common. Statistics for the British navy during the late 18th century show that accidents and diseases took many more lives than enemy action. Respiratory diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis were rife, as were illnesses from bad food and drink. In the tropics, malaria and yellow fever (the "black vomit") were added hazards.

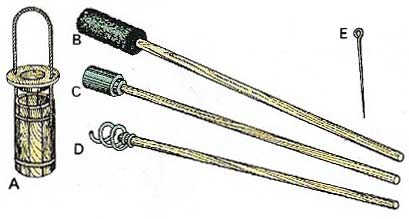

Figure 5. Gunnery procedure changed little between 1560 and 1860. The powder cartridge was carried from the magazine in a box (A) to protect it from sparks.It was pushed down the gun's barrel with a rammer (C) and pricked through the touch hole with a priming wire (E). The barrel was swabbed, after firing, with a sponge (B) to extinguish embers. The worm (D) was used to extract unfired charges.

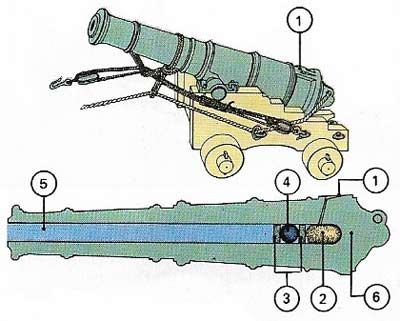

Figure 6. Naval cannon had a touch hole (1), cartridge (2), wads (3), shot (4), muzzle (5), breech (6).

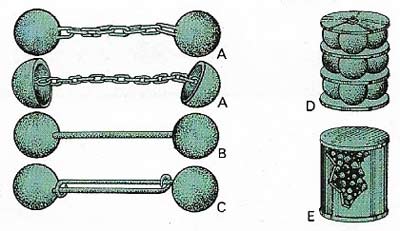

Figure 7. Types of disabling shot included chain (A), bar (B), elongating (C), grape (D), and canister (E).

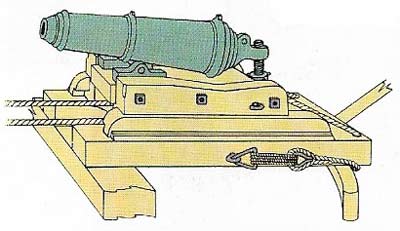

Figure 8. The carronade or "smasher", first fitted in 1779, was a short, stubby gun that fired a heavy shot and was deadly at close range. Light in weight and more maneuverable than other guns, it was mounted on the upper decks.

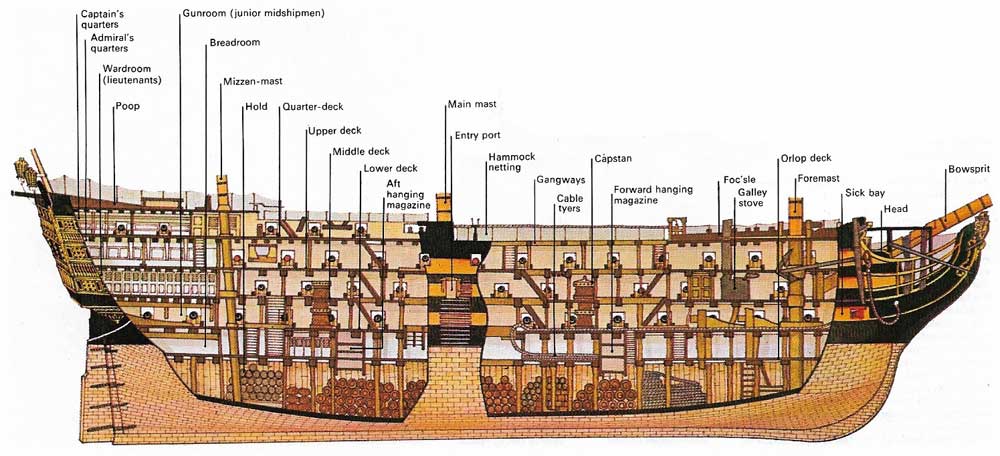

Figure 9. HMS Victory (1765) was a typical "first-rate" ship of the period. She carried 104 guns: 1 12-pounders on the forecastle, 12 12-pounders in the quarter-deck, 30 12-pounders on the upper gun deck, 28 24-pounders on the middle gun deck, 30 32-pounds on the lower gun deck, and 2 68-pounder carronades. She carried 850 officers and men.

Nations dependent on sea trade have always needed fighting ships to protect their sea lanes. Peaceful maritime commerce has usually been the result of an acknowledged naval supremacy on the part of one nation or another. By building up sufficient naval strength. interlopers have been able to achieve dramatic reversals of commercial power, as when the Arabs supplanted the Byzantines in the 15th century or when the Spanish were pushed aside by the Dutch and English in the 16th and 17th centuries. Some nations used ships for attacking other countries, as when the Vikings in their longships terrorized eastern Britain in the 9th century.

Galley warfare

An early reference to naval warfare in Egyptian temple reliefs of the second millennium BC shows a battle between the Egyptians and the "Sea People", with the former using oared sailing boats and the latter pure sailing boats. The Egyptians won, perhaps because of the superiority of their galleys.

The ancient Greeks, Phoenicians, and Romans had galleys with up to three (and perhaps more) staggered layers or banks of oars (Figure 1). These boats carried an auxiliary square sail on a single mast. Bows, arrows and catapults were not decisive weapons and an engagement usually had to be decided by boarding the enemy. Because of the sweeps (oars) this could be done only by head-on attack and the ram was a useful means of holding or capsizing an adversary.

Galleys survived until the early 19th century in some areas with remarkably little alteration, the major changes being the replacement of staggered sweeps by a single bank of longer sweeps powered by more men, and the replacement of the inefficient single square sail by triangular lateen sails on one or more masts.

|

| The 16th-century Venetian galley had a lateen rig, one bank of oars, a ram which doubled as a boarding bridge and five guns placed in the bows. |

The demise of the galley followed the development in northern waters (unsuitable for galleys) of maneuverable sailing men-of-war, which could fire devastating broadsides. The galleys could carry at most only five guns placed in the bows and were no match for the men-of-war after the 16th century. The last great galley battle was fought off Greece at Lepanto in 1571 when the Turkish fleet was defeated by a combined southern European force.

During the Middle Ages, there was no difference between the design of merchant and fighting ships; the former could be converted readily into the latter if soldiers were carried instead of cargo and wooden battlements were nailed on the bows and stern (the origin of the forecastle and quarter-deck). In fact, the distinction between the type of vessel used for trade, war and piracy was hazy until the 17th century and even up to the 19th century when privateers or corsairs were easily adaptable.

Importance of artillery

Light anti-personnel artillery was fitted on the rails of vessels during the fourteenth century and the great ships of the early Tudor period had gun ports pierced in the hull. Larger ships of this period were built primarily for naval purposes but would often engage in trade. The same was true of the Elizabethan galleon and in the Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century the Dutch fleets were essentially composed of the large two-decker trading vessels (known as "East Indiamen") of the Dutch East India Company. By that time, however, the fleet on the English side was purely naval and included some ships with three gun decks running the whole length of the ship. The upper decks such as forecastle and quarterdeck often carried guns as well.

|

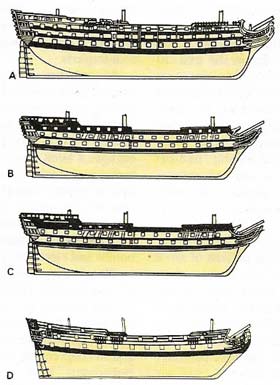

| Men-of-war were classed into rates from the 1650s until the end of the era of sailing navies. Rates were based on numbers of guns carried (excluding the carronades) and were altered several times during the era of the line-of-battle ship. In Nelson's day first-raters (A) had 100 or more guns on three decks, second-raters (B) had 90 to 98 guns on three decks, third-raters (C) had 64, 74 or 84 guns on two or three decks and fourth-raters (D) had 50 on a single deck. Only the first three rates were classed as ships of the line. Fourth- and fifth-raters (32–44 guns) were frigates. Sixth-raters (20–28 guns) were sloops and brigs of war. |

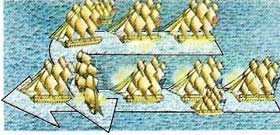

Up to the time of the Anglo-Dutch wars, naval tactics remained fairly similar to those used by the galley; ships formed a line abreast and "charged" the enemy. But the increasing importance of artillery and its broadside placement led to the line-of-battle tactic in which ships forming the line presented a formidable wall of guns. Only three- and two-decker ships were included in such lines and were known as "ships of the line". Two opposing lines would sail parallel to one another, firing broadsides in an attempt to create confusion in the enemy line so that it could either be pierced or divided.

|

| Naval fleet tactics of the 17th to 19th centuries were based on a line of battle with two- and three-decker ships forming a line ahead and frigates stationed outside to relay flag signals. |

Crossing an enemy's bow or stern not only ensured safety from his fire (which could be aimed only sideways) but also provided the opportunity to rake him. The bow and stern were the weak spots of a ship and shot plowing through the whole length of a gun deck was particularly lethal. The side which achieved the windward line had the advantage of being able to disengage more easily in case of trouble. In addition, an enemy could be holed below the water-line (exposed as the ship heeled with the wind).

Close-range fighting

Attack at close quarters remained an important tactic and in the Napoleonic wars the British fleets made effective use of a large-bore, short-range gun called the carronade (Figure 8). The British traditionally aimed at smashing the enemy's hull, while the French, firing on the uproll, concentrated on rigging and upperworks.

Beginning with small, paddlewheel warships, navies experimented with steam engines early in the 19th century. Engines were fitted in ships of the line in the 1850s and in the next decade the appearance of the rifled shell gun rendered the "wooden walls" obsolete and ushered in the ironclad.