origins of film

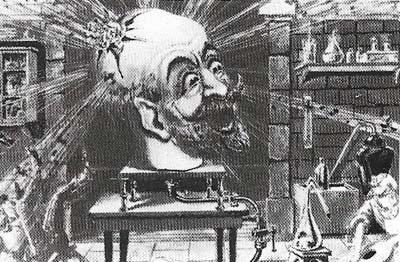

Figure 1. Georges Melies's poster for his 1901 film The Man with the India-rubber Head captures the delight in novelty and magic that led Melies's to pioneer many cinematic tricks. A theater proprietor, he saw film mainly as a marvelous new medium for illusions such as the pumping up of a head to the point of explosion. He also had considerable gifts of fantasy and comedy, best seen in Journey to the Moon.

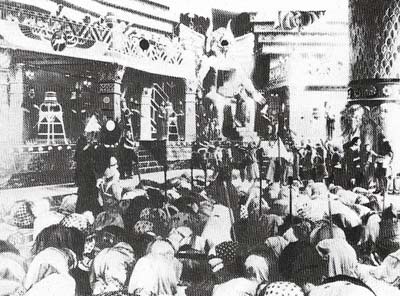

Figure 2. The first genuine film epic was Cabiria (1914), running four hours and deploying massive scenic resources to capture the splendor of ancient Rome. It was the culmination of the Italian cinema's prewar interest in historic themes, which had already produced the nine-reel Quo Vadim? – a film that convinced American producers that the public wanted long feature films instead of one or two-reelers. Cabiria's director Giovanni Pastrone, achieved an impressive silent

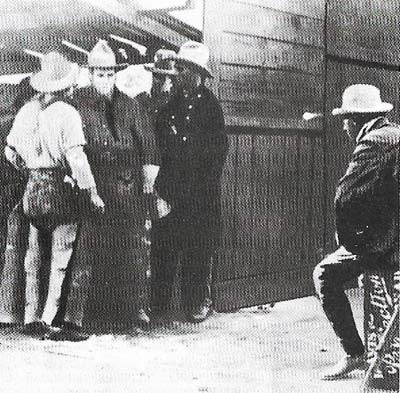

Figure 3. David Wark Griffith (center) was the acknowledged master of silent film in 1919 when he was photographed with two of the highest-paid stars of the day, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. In The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, Griffith used the resources of cinema on a scale and with an emotional in intensity that profoundly influenced most other directors. Although he experimented boldly, his greatest achievement was the expressive quality he brought to the telling of a screen story.

Figure 4. Hollywood began, according to screen legend, in a barn in which Cecil B. DeMille (seated on a humble box) directed The Squaw Man in 1913. The barn (later enshrined in the Paramount lot) had in fact been used for earlier short films, but The Squaw Man was the first big commercial success filmed there and Hollywood soon began to mushroom.

Figure 5. The Odessa steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin (1925) is a landmark in the history of films as art. Sergei Eisenstein intercut shots of advancing Cossacks with close-ups of the impact of their bullets – a blinded woman, a runaway pram - to convey the drama and horror of revolution.

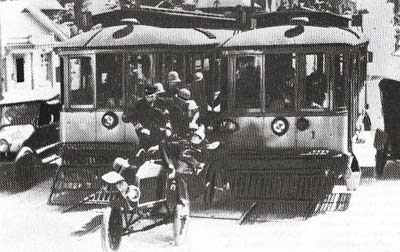

Figure 6. Film stunting and slapstick were born in the Keystone studio of Mack Sennett (1880–1960) who in 1912 got together former music hall comedians, acrobats, cowboys, daredevils, and other uninsurables, put them into policemen's uniforms and sent them on an endless series of surrealistic escapades as the Keystone Kops. Sennett's one-reelers were fast, furious, funny – and dangerous. They invariably ended in a chase sequence with cars, trams, or other vehicles careering into screen infinity.

Figure 7. Al Jolson, blacked up for his part in The Jazz Singer (1927) told audiences "You ain't heard nothin' yet" and the line became immortal as the first sound dialogue to be heard in a feature film. Sound had been tried as early as 1900 and Fox Studios had produced a dialogue "short" before The Jazz Singer, but it was the huge popularity of the songs and a few lines of dialogue in the Jolson film that persuaded Hollywood businessmen that the daunting cost of re- equipping for sound would be recouped at the box-office. The first all-dialogue film was Warner's The Lights of New York, in 1928. Sound revolutionized the cinema, but it was some years before technical improvements restored the artistry achieved in the silent era.

Figure 8. Charlie Chaplin's little tramp (poignant in City Lights) was the first immortal screen character. Beginning in 1913, Chaplin (1889–1977) touched millions with his superb artistry.

Moving pictures began as a technical novelty based on the brain's inability to detect a fractional gap between a rapid series of still photographs. Nobody at first suspected that a toy would become the most significant medium of communication, entertainment and art of the 20th century.

The illusion of movement

Asian shadow plays, European magic lantern shows of the 18th and 19th centuries, and devices such as Emile Reynaud's Praxinoscope, which projected images from a spinning drum, were early methods of producing the illusion of movement on a screen by back-lighting and magnification. After the patenting of the Eastman roll film, the way was open in 1891 for W. K. L. Dickson of the Edison laboratory to photograph vaudeville acts at 46 frames a second on a perforated film and run them back in a peepshow machine the Kinetoscope. Louis Lumiere (1864–1948) and his brother Auguste (1862–1954) combined this with magic lantern techniques to project the first public cinema show in Paris on 28 December 1895.

Within the next five years the techniques of double exposure, fast and slow motion, reverse projection, fades, dissolves, and close-ups were all discovered, many of them by Georges Melies (1861–1938) who became fascinated with film magic after he observed a bus turn into a hearse when his camera jammed while he was recording a street scene. Filming from a fixed position, Wiles pioneered a cinematic fantasy linked to the artifice of the theater (Figure 1).

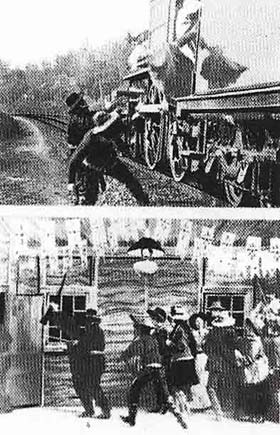

One of the first film-makers to recognize that the camera could move freely and build up stories by a kind of visual shorthand was Edwin Porter (1869–1941). His two 1903 films, The Life of an American Fireman and The Great Train Robbery, had a sensational impact on the public, largely as a result of editing innovations.

|

| Edwin Porter's juxtaposition of images in The Great Train Robbery created a sense of movement and speed the transformed film technique and lead to endless imitations. He switched from outdoor shots of bandits making off with their loot (top) to interior shots of a telegraph operator being released in bursting into a dance hall to alert the local citizenry and lead the pursuit (bottom). The freedom of which Porter moved his camera and edited separate shots into a thematic relationship astonished audiences who are used to watching only the progression of events within a fixed scene. His "Western" ran for 10 minutes in 15 shots. |

The early film industries

Beginning in cheap nickelodeons patronized by the poor migrant populations of America's cities, the American film industry quickly became a medium of mass entertainment, turning out simple one- or two-reel morality sketches. The fledgling European industries sought greater artistic respectability by using well-known stage actors in film versions of the classics. Comedians such as Max Linder (1883–1925) at the big Pathé studios in France began to break away from this literary form of cinema, establishing a basis for the style of visual slapstick that would soon make Charles Chaplin (Figure 8) and Buster Keaton (1895–1966) famous. In Italy, the nine-reel Quo Vadis? (1912) and the still more spectacular Cabiria (1914) introduced the idea of long feature films (Figure 2). In America, D. W. Griffith (1875–1948) (Figure 3) was encouraged to make The Birth of a Nation (1915), a massive interpretation of the Civil War which incorporated techniques he and others had been developing since 1908. Working almost like a novelist, Griffith composed his story by intercutting close and long shots, flashbacks, and parallel action to create powerful emotional effects.

The creative influence of Griffith and such directors as Thomas Ince, the huge popularity of Mack Sennett's slapstick Keystone comedies (Figure 6), and the damaging effect of World War I on the European film industries, all combined to make the fiercely competitive American industry dominant by 1920. Hollywood (Figure 4) became the cinematic capital of the world and profited from the escapist hedonism of the jazz age. By the mid-1920s it was financially powerful enough to raid Europe for the talented directors who had emerged in a postwar flowering of film art.

Under the influence of its Expressionist painters, Germany was pre-eminent with directors such as G. W. Pabst, Ernst Lubitsch, Fritz Lang, and F. W. Murnau, whose The Last Laugh (1924) astounded Hollywood by its technical versatility and psychological penetration. Surrealism, Dadaism, and Impressionism all had an impact on the more subtle cinematic tradition of France where Abel Gance had led developments and where Rend Clair and Luis Bufiuel were beginning work.

In Sweden, Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjostrom had explored the possibilities of filming in natural settings. And in Russia, Lenin's declaration that the cinema was "the most important art" led to the first nationalized film industry. To express the message of the Soviet revolution, montage editing was brilliantly refined by Vselvod Pudovkin and by Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948), who moved his film forwards in a series of shock "cuts" (Figure 5).

The arrival of talkies

With the spread of radio, Hollywood recognized by the mid-1920s that to hold its audiences the cinema would need greater depth than could be provided by mime backed with titles and orchestral or piano music. Workable sound systems had existed from the early days of film, but recording and amplifying systems now became efficient enough to make synchronized sound-on-film fully practicable. Although businessmen feared re-equipment costs and problems in marketing English-language films abroad, the success of The Jazz Singer (1927) precipitated events in Hollywood (8). Within three years the American film industry switched to talkies and was amply rewarded with a 50 percent rise in audience numbers.