Greek mystery religions

A group dancing around a priest of Dionysus. According to legends, the maenads' wild rites were first performed by the women of Thebes, who were struck with a divine madness by Dionysus.

Greek vase-painting of about 500 BC depicts a maenad in ecstasy

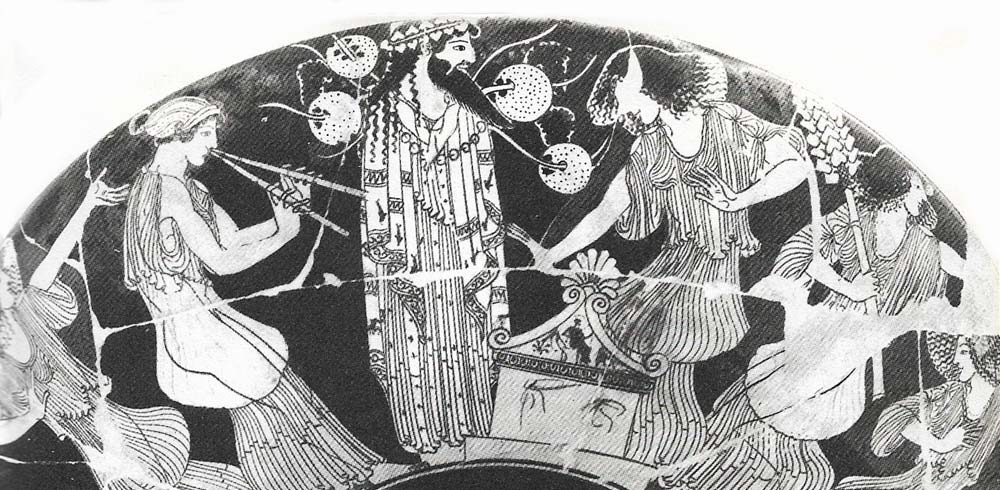

Persephone banqueting with the king of the underworld, froma Greek vase-painting of about 440 BC. In the mysteries of Demeter, Persephone's captivity was associated with the earth;s infertility in winter.

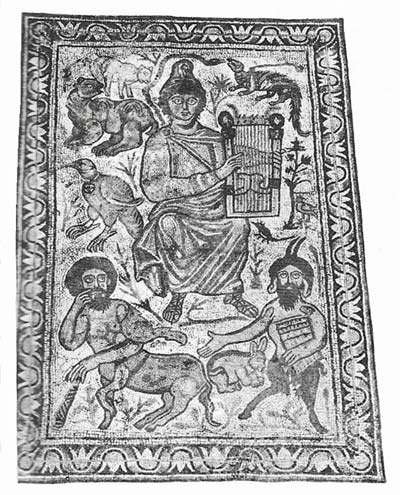

Mosaic from an early Christain church in Jerusalem depicts Christ as Orpheus, taming wil beasts with the music of his lyre. Greek devotees of Orpheus sought to tame the wild or "titanic" side of their nature by ceremonial purification and self-denial, so that their soulds might eventually be released from the cycle of rebirth.

Greek religion was at its most personal and ecstatic in the worship of Dionysus. The cult of this vegetation deity began in Thrace; but, in time, it gathered elements of other fertility cults of Asia Minor. Dionysus was a marked contrast to Apollo, who represented the harmony and proportion so evident in the arts of classical Greece, of which he was patron. The Dionysian religion was partly an outlet for emotional needs that the Homeric and state religion not only neglected but looked on with suspicion.

The Dionysian rites were violent, but essentially sacramental. The devotees would meet on remote mountainsides, where, stimulated by wine and wild music, they danced ecstatically. At the climax of the rite, they ate the raw flesh of an animal, in which Dionysus was supposed to be present. The worshipers – very often women called maenads—thereby gained a sacramental union with the god. The cult was immortalized by Euripides' ironic and tragic treatment of it in the Bacchae.

The Dionysian cult gained in mystical significance when Orphism, a movement that became influential in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, incorporated its central features. The legend was that Dionysus, under the name of Zagreus, was son of Zeus by the earth-goddess Semele, but he was killed and eaten by the Titans, the gods of evil who were at war with the Olympians. Zeus in anger burned up the Titans with thunderbolts and from their ashes the human race was formed. Hence man is a combination of evil (he is Titanic) and good (for he contains an element of the divine Zagreus).

The Orphics made this dualistic doctrine the basis for an elevated and ascetic mystery religion that tamed the wilder side of the Dionysian cult. They believed the body was a tomb that imprisoned the soul; they taught reincarnation, and in this and other ways influenced the religious thinking of Plato. The soul could escape ("attain blessed release") from the round of reincarnation by cultivating moral purity; impure souls were liable for punishment in Hades. In their doctrine of the soul, their asceticism, and food taboos (they abstained from eating eggs and beans), the Orphics had much in common with the Pythagoreans. People joined the Dionysian and Orphic cults partly because they both promised a kind of immortality, whether in sacred union with the god or in a future life of blessedness.

Like the Dionysian cult the mysteries of Demeter, the "corn-mother," at Eleusis, outside Athens, focused on a vegetation deity. According to the myth, Demeter's daughter Kore was carried off by Hades, the god of the underworld. Demeter searched for her sorrowfully with a lighted torch, and after many difficulties, Kore was restored to her. However, by a trick Hades bound her to spend one third of every year with him as Persephone, his queen. To herald her annual return to the earth in spring, Kore the corn-maiden sends up shoots of the new crop from the underworld. In this way, concern for a future life and agricultural religion were synthesized.

|

| The appearance of the first spring crop meant Persephone's return to earth as Kore the corn-maides, depicted in this medallion. |

The Eleusinian mysteries themselves, confined to mystae or initiates, also came to incorporate the cult of Iacchos or Dionysus. The chief ceremonies took place in the autumn. After a procession from Athens to the sea, the initiates imitated Demeter's search for Kore by wandering on the shore with lighted torches; all that first night they kept vigil. On the following days came the rites of initiation: The mystae displayed sacred objects in a blaze of fire and performed ritual dramas that symbolized the death and resurrection of the corn. The solemnity of the Eleusinian liturgy made a powerful impact. It was more by this personal impact than by the revelation of any secret truths that the mysteries had their power. From the time of Pericles (died 429 BC), the festival became pan-Hellenic, and for a long time it remained one of the most sacred expressions of personal religion in the Greek world. Eleusis retained its power until a very late period : A number of Roman emperors became initiates, and Claudius (AD 41–54) even wished to move the mysteries to Rome. The destruction of the temple at Eleusis by Alaric the Goth in the fourth century brought the mysteries to an end.