the Greeks to the rise of Athens

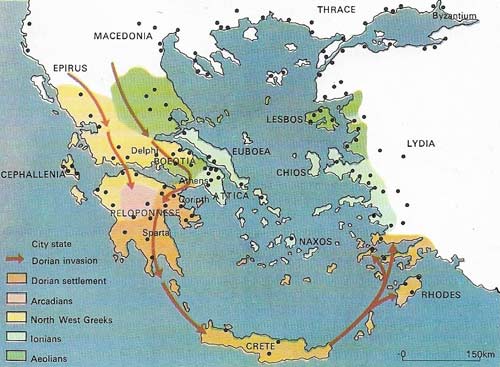

Figure 1. Little is known of the history of Greece between the arrival of the Dorians (c. 1200 BC) and the dawn of the Archaic period (c. 800 BC). Homer describes a society of small agricultural communities grouped round citadels and led by kings and aristocracies that still retained many of the features of Mycenaean civilization and had little trade or commerce. By the time of Hesiod (8th century BC), whose narrative poems give a description of the early Archaic period, trade and commerce were increasing, monarchy had generally been replaced by oligarchy and the city was becoming the focus of political life.

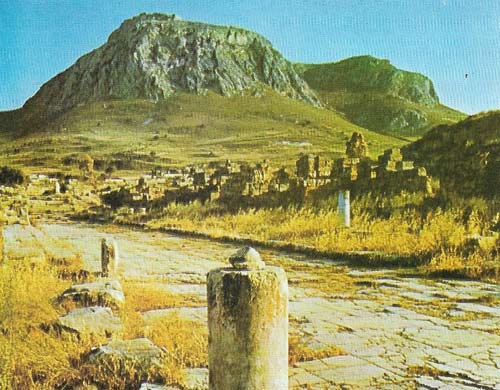

Figure 2. The landscape of Greece, with its limited fertile plains and harsh mountains, became a significant factor in the rise of small communities such as Corinth (shown here). Travel was difficult and economic and political life tended to be concentrated in confined areas. The Greeks were convinced that these small independent units were the most natural size for a satisfactory political life. This attitude, combined with constant diplomatic and military maneuvering between states, meant that wider unity was never attempted, although the idea of a distinct Greek identity and a feeling of cultural superiority to outsiders did exist.

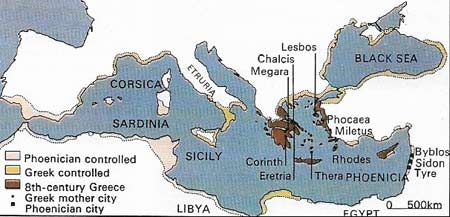

Figure 3. Colonization was used to send surplus and disaffected populations to found cities in new regions. The first phase began about 750 BC with expeditions to the west, where the Greeks found the Phoenicians already well established in many areas. They were able to settle in Sicily, southern Italy, France, and Libya. About 650 BC the Greeks began to move into the Black Sea region until there where colonies round almost all its shores. By the 6th century BC, the colonies were sending enough food back to Greece to feed the expanding population and thus reduce emigration.

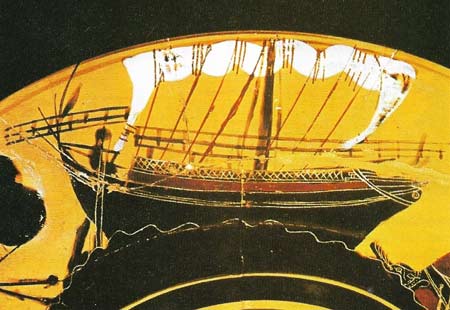

Figure 4. The Greeks traded with the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, and the people of the Middle East as well as between colonies and mother cities. In states bordering the sea, such as Athens and Corinth, trade became an important source of wealth. Shipbuilding and navigation were therefore vital skills.

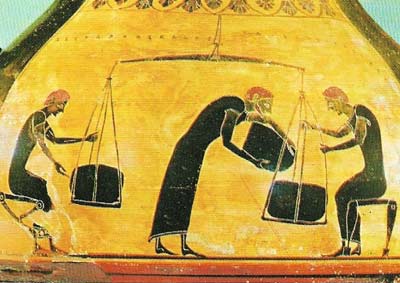

Figure 5. Trade and commerce were free to develop after the city-states had been established, and the system of barter was replaced by more regulated methods. Various systems of weights and measures were developed (such as this one on an Attic black-figure amphora, showing men using a balance scale), but no single system became dominant. Precious metals were used for exchange either in the shape of weapons or as pieces valued by weight. By the end of the 7th century money had been invented. The issuing of coinage soon became the privilege of governments and not of individuals.

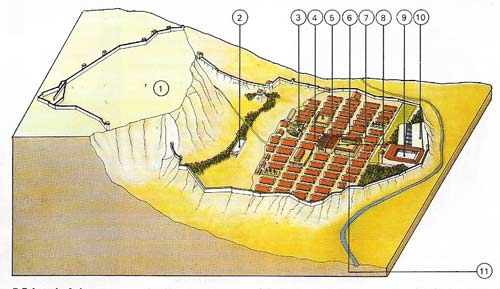

Figure 6. Priene in Asia Minor was a model of Greek town planning. Most cities grew haphazardly, but few were as well planned or showed so clearly the essentials of a small city-state of only about 4,000 inhabitants. The citadel or Acropolis (1) stood at the top of the cliff with the main city below it. The principal features were the sanctuary of Demeter and other gods (2); the huge theater (3), possibly the oldest Hellenistic example, which could accommodate an audience of 5,000; housing blocks (4), each with four to six dwellings; buildings for the council and courts (5, 6); the agora (11), which was the marketplace and heart of the community, adjoining the main street (8); the sanctuary of Zeus (7); the gymnasium (9); and the stadium (10).

Some time about 1200 BC, Greek civilization underwent a major change. Dorian tribes moved through the peninsula from the north and settled, mainly in the Peloponnese. The existing peoples were assimilated or confined into smaller areas, and Ionians and Aeolians in particular were pushed out across the sea to found cities in Asia Minor.

The development of institutions

Major social changes must have accompanied this upheaval, but little detail is known of the next 400 years; much of what we do know comes from the two epic poems by Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey. It is, however, possible to identify several important developments that were of major significance for subsequent Greek civilization. The use of iron became widespread for tools and weapons; a phonetic alphabet was developed and more or less standardized; and a feeling of national consciousness arose – a racial and intellectual identity bound up in the use of the word Hellas to describe the whole Greek world. At the same time a pantheon of gods that appear in Homer's poems was formed, religious ceremonies developed and the importance of shrines such as Delphi became generally accepted, and the city state was adopted as the most important political, economic and social unit.

|

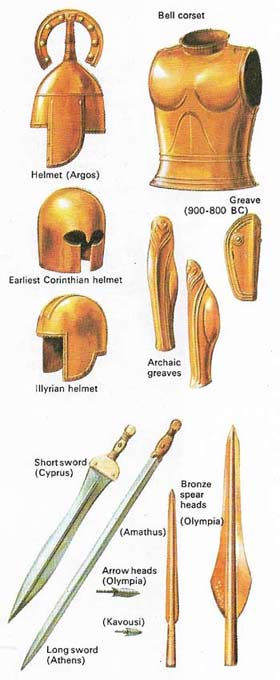

| Bronze arms and armor were used by the aristocratic warrior's of Homer's poems, who fought in individual combat. But iron began to supersede bronze before 700 BC and tactics changed fundamentally, with heavily armed infantry (hoplites) fighting in a well-disciplined mass formation – the phalanx. Many hoplites came from outside the aristocracy (although they had to be wealthy enough to provide their own equipment) and this helped to weaken the old social order. |

The rugged geography of Greece played a major part in making the inhabitants of each valley regard themselves as a separate entity and Greece became a patchwork of small states each of which guarded its independence jealously (Figure 2). They varied greatly in size; Athens succeeded in subduing Attica and no other states developed there, while Thebes failed to overcome Boeotia and at least 12 states existed there. Writing in the 4th century BC, Aristotle mentions the existence of at least 150 states. The size of the city-state was important for Greek political development because a firm belief developed that a satisfactory political unit must be small and totally independent. A Greek had a series of loyalties to Hellas, to his city state and to his tribe within the state – but loyalty to the city was the most powerful and the idea of a larger political unit was never developed. During this period the Greeks also evolved the belief that government must be based on a known constitutional and legal framework.

Agriculture, trade and politics

Economically, agriculture was all-important and as the cities developed, the link between them and the country remained strong. However, some states became increasingly involved in trade and industry (Figure 4) and a definite class of traders and craftsmen evolved. Politically, by the mid-seventh century BC most states had moved away from the monarchies described by Homer and were ruled by oligarchies of the richest and most powerful citizens. A privileged or noble class held all political, military and religious power and there was usually tension between them and the common people.

|

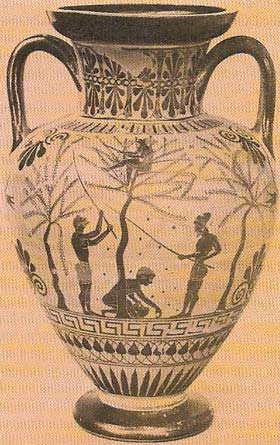

| Greek agriculture, represented by the olive harvest shown on this 6th-century BC amphora, was always faced with the difficulty of providing sufficient food from the relatively small area of fertile land. The natural consequence of an expanding population faced with a limited food supply was emigration, first across the Ionian Sea and then throughout the Mediterranean. But overpopulation was only part of the reason for emigrating: the nature of aristocratic control of land resources meant that the distribution of agricultural land was by no means equitable; the resulting social tensions naturally encouraged the tendency to emigrate. |

This tension was made worse by increasing population and a safety valve was found in colonization (Figure 3). States organized expeditions to found new cities overseas, but once founded these new cities were completely independent of, although they retained close links with, their mother cities. From about 750 BC migration established Greek cities throughout the Mediterranean.

Colonization did not solve the problem of class struggle and the archaic Greek world (Greece between 800 and 500 BC) saw the widespread appearance of tyrants, a word originally applied by the Greeks to men who seized power unconstitutionally and ruled – either well or badly without legal backing.

New political systems

In Athens attempts were made by Solon (c. 640–c. 559 BC) to remove the economic problems that lay at the root of the class struggle and reform the legal framework of the state to protect the weak. Power was seized in 545 by Pisistratus (c. 600–527 BC) who increased the rights of the common people and brought the nobility under the rule of law. These developments formalized the democratic system that ruled Athens for the next two centuries.

The same pattern was followed in other states; tyrants rarely lasted long. Some states, such as Sparta with its peculiar constitution, and Corinth with a strong oligarchy, avoided the tyrannical stage completely.

Until the middle of the 6th century BC the Greeks were largely unaffected by out-siders, apart from trading contacts (Figure 5). The situation altered when the Lydians extended their power over the Greek states of Asia Minor and were succeeded in 546 by the Persians. Neither overlordship was oppressive, but in 499 the Greeks rose in revolt and succeeded in temporarily reasserting their independence. There was, however, little unity among them or support from the mainland, and in 494 the Persian emperor Darius was able to crush the revolt. He followed this up by reimposing his power in Thrace and Macedonia and then in 490 launching a major invasion of Greece.

Athens, as the largest state, was his immediate target and she called for help from the others, but before this could arrive her troops, who were significantly outnumbered, met and decisively defeated the Persians at Marathon. Darius' army withdrew, leaving the Greeks still disunited but convinced of their superiority over the "barbarians".