Hannibal

Hannibal.

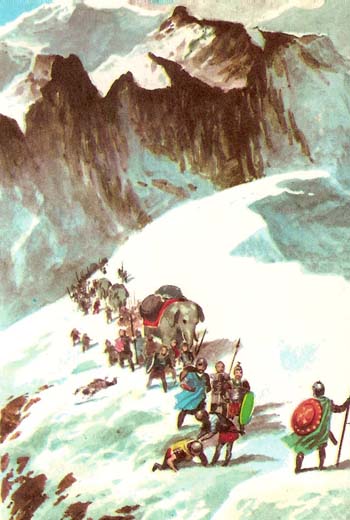

Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps.

Hannibal heading for exile.

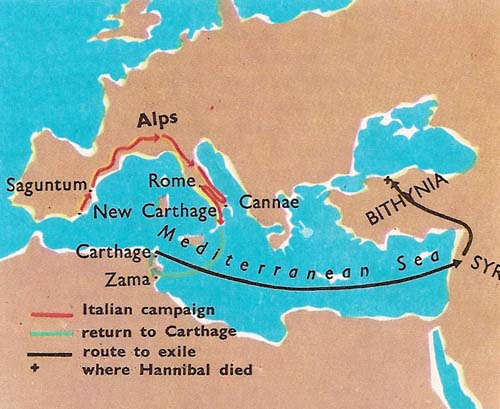

Route of Hannibal's campaign in Italy and his journey into exile.

Hannibal, one of the greatest generals of all time, and Rome's most dangerous enemy, was born in Carthage in 247 BC while his father, Hamilcar Barca, was fighting the Romans in Sicily in the First Punic War. In this war Carthage lost her flourishing colonies in Sicily because she lost control of the sea to the Romans at the battle of Aegates Islands.

Hannibal's oath

After the war many of the Carthaginians' African soldiers mutinied, and the Romans seized the opportunity to demand Corsica and Sardinia as well. From then on leading Carthaginians felt that they could never trust the Romans. Hamilcar Barca, now appointed Carthaginian commander in Spain, in fact took his nine-year-old son, Hannibal, before an altar, and made him stretch out his hands over a newly sacrificed victim and swear that for as long as he lived he would hate the Romans. All his life Hannibal kept that oath.

In Spain

When Hannibal was 18 his father died, and when he was only 26 he himself succeeded his brother-in-law as supreme commander of the Carthaginian forces in Spain. He and his family used their time well. By trade and conquest they built up in Spain an empire to replace the lost wealth of Sicily, and they enlisted and trained many fine fighting-men from the warlike Spanish tribes. Hannibal himself also made friends with various Gallic tribes, especially those which controlled the passes over the Alps. The Gauls had recently been defeated by the Romans, and Hannibal knew that if he acted quickly he could count on their support.

In 219 BC, after eight months of siege, Hannibal captured the Spanish city of Saguntum, which, although 100 miles south of the River Ebro (frontier of the Carthaginian empire in Spain), happened to be an ally of Rome. This he knew meant renewed war with Rome (the Second Punic War). But how could Rome be attacked? Not directly from Carthage, because the Roman fleet controlled the sea; so Hannibal dared what no one thought possible; he decided to march his great army over the Pyrenees, across Provence, and over the Alps, to crash down like a thunderbolt into northern Italy. He hoped and expected that Rome's allies in Italy, shielded by the Carthaginian army, would seize their chance to desert her, and that Rome would be forced to yield.

Across the Alps

Leaving part of his army therefore under his brother Hasdrubal to defend Spain, he set off from New Carthage (Cartagena) on his great march with a force probably of nearly 50,000 men, with 37 fighting elephants. After crossing the Pyrenees and the River Rhône, which caused him some difficulty because of his elephants, he at last came to the Alps. We do not know which pass he used, whether the Mont Cenis or the Mont Genévre; but the various delays which had forced him to cross the Alps as winter was approaching, and the hostility and treachery of some of the Gallic tribes, caused him to lose nearly half his army. When he reached the plains of northern Italy there remained of his original force only 20,000 foot, 6,000 horse, and 10 elephants, all but one of which died soon afterward. If he had not been able to inspire his men with faith and the will to win, it is unlikely that they could ever have crossed the Alps at all. Hannibal himself lost the sight of one eye from a fever brought on by exhaustion.

Campaigning in Italy

Hannibal soon showed his amazing gifts as a general. His first great victory was at the River Trebia, where the Carthaginians warmed themselves at fires and rubbed their bodies with oil to keep out the cold, before fighting Romans whom they had enticed into wading waist-deep across the icy stream before breakfast. Next Hannibal lured another Roman army into a narrow pass between Lake Trasimene and the mountains where his cavalry lay hidden by thick mist until ordered to fall upon the Roman rearguard and close the trap.

After these two defeats the Romans tried different tactics. Fabius, the new Roman commander, avoided a pitched battle, but kept close to Hannibal as he marched south into Campania. When Hannibal was about to return across the Apennines, Fabius blocked all the passes except one, and waited for him there. But Hannibal caught a herd of cattle, tied lighted torches to their horns and drove them at night in a different direction. In the darkness the Roman guards mistook the cattle for the Carthaginians and followed them, while Hannibal's army was able to pass through unobserved.

But Fabius' delaying tactics were very unpopular among the Romans. Next year the consuls determined to fight another pitched battle with Hannibal. Hannibal chose his ground carefully, at Cannae. With excellent discipline, the Carthaginian center deliberately fell back before the Roman attack but did not break ranks, while the wings closed upon the Romans, who thus were surrounded and massacred. Cannae was the greatest of Hannibal's victories. Never again did the Romans fight a pitched battle with him on Italian soil.

Hannibal's failure and recall

And yet, with all this success, Hannibal never broke the power of Rome. One might have expected him to march on Rome after his victory at lake Trasimene, or after Cannae; but he knew how difficult it would be to capture Rome with its strong fortifications. He had hoped that after his victories Rome's allies would desert her. Many of the Greek cities in southern Italy (notable Capua) did so, but central Italy stood firm and would not give him a base. The Romans settled down to years of wearing him out with "Fabian" tactics. Roman naval supremacy prevented his receiving any reinforcements direct from Carthage; and Roman generals in Spain succeeded in preventing reinforcements from coming to him by land until 207 BC, when his brother Hasdrubal managed to cross the Alps with a relief army. But the Romans intercepted and defeated him at the battle of the River Metaurus before he could join Hannibal.

Eventually the Romans, under Scipio, attacked the Carthaginians in Africa itself, and Hannibal was recalled to defend his native country. There, at Zama, south-west of Carthage, in 202 BC, the decisive battle took place, and Hannibal was defeated.

The war over, Hannibal tried to save Carthage from the results of defeat: but when he discovered his enemies were planning to hand him over to the Romans he went into exile, where at last he killed himself rather than submit to Rome.