Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism

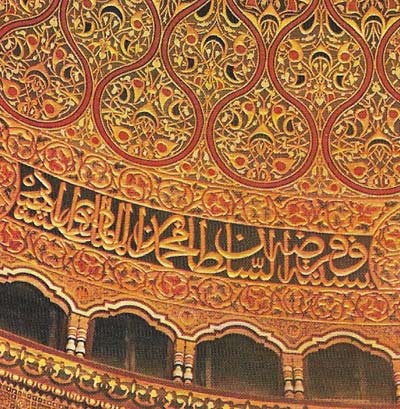

Figure 1. The arabesques in the interior of a Muslim mosque represent divine unity in a symbol that is at the same time logical and rhythmic, mathematical and melodious. For a Sufi, one who has reached the goal of Islam's inner way, divine unity means much more than that there is only one God rather than several. It is also a key that opens the meaning of creation as a revelation of the Absolute, like white light diffused through a prism. As a microcosm, man gathers up all the attributes reflected separately by other creatures. His greatest potential is to reunite all the colors of the spectrum into a spark of divine light.

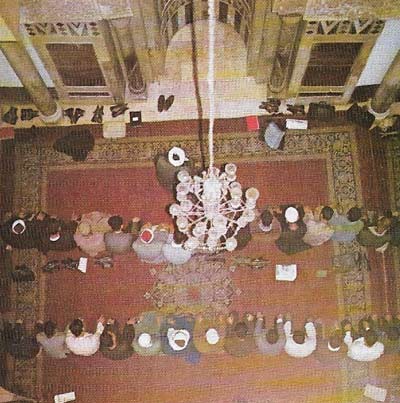

Figure 2. Prayer at specified times, five times a day, is one of the fundamental practices prescribed by Mohammed and known as the Five Pillars of Islam. The other four are declaration of faith in Allah, almsgiving, fasting during the month of Ramadan from dawn until sunset, and making a pilgrimage to Mecca in one's lifetime. Even fulfilling the law in an external way can help a Muslim understand his condition in life. A Muslim does not seek to go beyond the basic requirements by "doing more" in an external sense but to realize more deeply what he is already doing.

Figure 3. The many-armed Hindu god, Shiva, symbolizes the many modes of divine energy. The apparent polytheism that many Westerners see in Hinduism is in fact adaptability. Hinduism is monotheistic in a massive way, for in it all creation and experience are one. Judeo-Christian monotheists would be asked by a Hindu: "Who are we to limit the forms in which Brahman may manifest itself?" A devotee may take hold of any of the forms, which are in fact generated only by our partial perception, to arrive at the One. He may use any method from asceticism to orgiastic abandon or from ritual poverty to industrious prosperity if it leads him to God-realization.

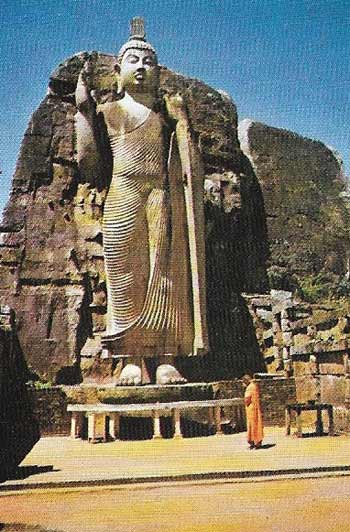

Figure 4. Gautama Buddha brought a teaching directed solely to one point: the extinction of suffering. He saw people everywhere making them-selves miserable through deluded belief in the reality of the ego. Rejecting displays of miraculous powers and speculations about metaphysical questions, he urged his followers not to rely on the achievements or the understanding of others as this might simply be woven into their own fantasies. "Be ye a refuge unto yourselves. Betake yourselves to no external refuge. Hold fast to the Truth as a lamp. Look not for refuge to anyone besides yourselves."

Figure 5. Buddhism is split into two main streams – Mahayana and Theravada. Devotees of the latter revere the personality of the Buddha, his teachings and the order he founded. They hold that the ideal Buddhist is a faithful follower of the Eightfold Path. Mahayana Buddhists regard the Buddha as one of many who have appeared in many universes. They hold that the ideal Buddhist is a Bodhisattva or one vowed to become a Buddha through the six virtues – generosity, morality, patience, vigor, concentration and wisdom. The Tibetan Buddhists, here ready for the Tsam dance, hold to a mixture of Mahayana and Bonism – an indigenous worship of natural spirits through ritual.

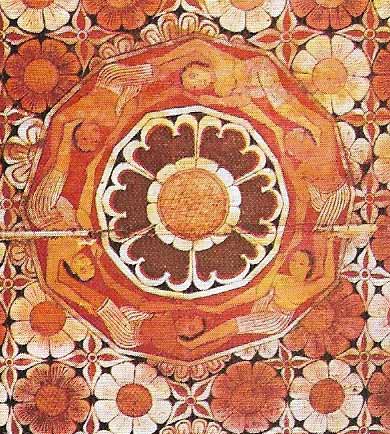

Figure 6. The Wheel of Life, the great Buddhist symbol of samsara, is the endless round of birth and death in which all beings are trapped who have not pierced through the illusions of the ego and stilled its cravings. In other versions the hub of the wheel depicts three animals representing lust (dove or cock), hatred (snake), and delusion (pig). These impulses generate a universe of conditioned existence.

Figure 7. Zen Buddhism first flourished in China in the 7th century AD and then spread to Japan in the 12th. There are two main branches – Soto and Rinzai. In the latter, meditation on such paradoxes as the "sound of one hand clapping" is used to awaken insights into what transcends logical distinctions. In Soto adherents sit silently in gardens such as this and meditate on what illumination arises. Both believe in mind-to-mind instructions from master to disciple with the aim of awakening the Buddha-mind that lies within every individual. Soto concentrates on teaching the common people the good ways.

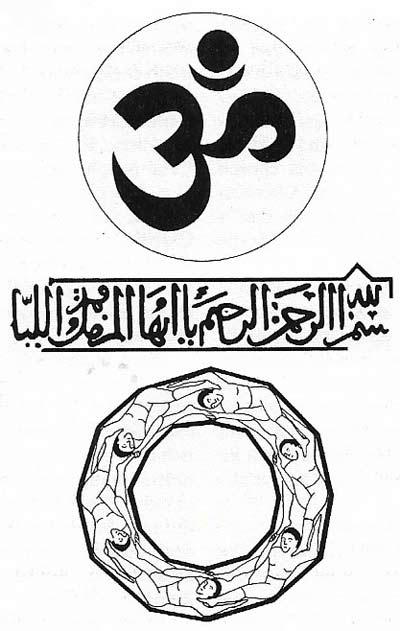

Figure 8. Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist symbols, reading from top to bottom, respectively, represent sacred aspects of their faith. The vast majority of these are to be found in North African and Asian countries. The syllable AUM (top) is a mystic sound representing the Eternal Essence, and uttered by Hindus during the most solemn moments of worship. The arabesque (center) is a rhythmically designed pattern of oneness in which, according to strict Muslim rules, no animate objects are represented. The Wheel of Life (bottom) means for Buddhists the continuing cycle of death and rebirth that taps mortals.

Islam, the youngest of the world religions, sounds again the message of God's unity – "There is no God but God". Recognition of this truth constitutes the act of submission by which a man becomes a Muslim – "one who submits". Conscious of his dependence, man acknowledges: "I am not the Absolute". Yet one who is called to the inner path of Islam also comes to recognize, "I am nothing separate from or other than the Absolute". Unity is reflected everywhere, drawing itself out like a beautiful arabesque (Figure 1) that baffles the eye as it continually turns back on itself.

The basis of Mohammed's teaching

According to the Islamic perspective, man is in need of divine revelation to remind him of the One Reality, which is never directly manifested in the world. Judaism and Christianity are recognized as founded on authentic revelations and Islam is said to offer the third and final revelation.

Mohammed, the founder of Islam, was born in Mecca in c. AD 570 and began to fulfill his prophetic function by denouncing the prevailing Arab worship of many gods. Confronted by powerful opposition, Mohammed and his followers became a social and political as well as a spiritual force. Following the teaching of the Koran, Islam developed both external and internal aspects of religion, providing laws for the guidance of a community as well as a way for the individual to unite with Allah (God).

Traditionally in Islam there is no separation between sacred and secular areas of life. There is no priesthood, no day reserved for worship. Instead, the law itself offers direction and an ideal of life that meets man's need. In the Islamic perspective, man sins not by wilful rejection of God, but by heedlessness or distraction. The required observances of Islam net as reminders of the relationship between that life and the Absolute.

The teachings and practice of Hinduism

For a Westerner the Hindu religion of India may be puzzling. In place of God and creation, he finds that Brahman (ultimate reality) is probably utterly impersonal and the phenomenal world is ultimately unreal. Even the idea of historical progression is overshadowed by the sense of a cyclic world drama of creation, preservation and destruction. Looking for clearly defined doctrines, the Westerner is instead plunged into a variety of methods and beliefs. For while Western monotheism seeks to protect the truth from distortion, in Hinduism the truth is left to protect itself (Figure 3).

The simplest – and therefore the most difficult – expression of the spirit of Hinduism is "Thou are That", which may be understood as a response to the deepest question men ask. Looking at the world around them, men saw in the sudden flash of lightning, in the invisible power of the wind, signs of energies beyond their control and asked: What is behind all this? Another form of the question is concerned with the mystery within man: Who am I? In a single moment of discovery comes the answer to both lines of questioning: The true Self (Atman) is the same as the ultimate ground of reality, Brahman – "Thou are That".

|

| The AUM symbol (OM) is a ritual and sacred Hindu syllable, rendered in Sanskrit calligraphy, that is understood as the fundamental sound of the universe. It is chanted both for the effect of its vibration on the worshipper and as a tangible symbol of the one fundamental Reality: Brahman, the Absolute. One interpretation of its three sounds (A, U, M) is that they represent the trinity of Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma. |

The Hindu revelation is not the focus of an historical event such as the revelation given to Moses, and does not mark a unique bridging of the gap between God and man such as that provided by the incarnation of Christ. It says that the Truth is in each person waiting to be realized. With this promise comes the warning "Neti, neti" ("Not this, not that"). One cannot identify either the Self or the Absolute with any particular thing. Belief in a separate self or ego is like an assumed identity that keeps us from realizing our true Self. In final wisdom the identity is laid aside and selfhood merged in an oceanic experience of That (Samadhi).

Fundamentals and precepts of Buddhism

Buddhism is more urgent and direct in its teaching than Hinduism, from which it grew. It sees ordinary existence as a nightmare that is not the less painful because it is unreal.

In the 5th century BC, Gautama Siddhartha, the son of an Indian king, woke from the nightmare. As the Buddha ("the awakened") (Figure 4) he was forever released from suffering and full of compassion for those who were still in darkness. The Buddhist believes that suffering is a universal fact of existence because of man's fundamental ignorance about himself and the world. The world is a process of continuous interaction of unstable compounds in which nothing lasts.

Whatever a man may take to be himself – body, mind, feeling, perception – is an obstacle in the form of the assertion "This is mine; this am I; this is my ego", which makes him the center of an imaginary drama of pleasure and pain, good and bad (Figure 6).

Some have seen in the Buddhist denial of the ego and emphasis on transience a pessimistic rejection of all values. What is negative in Buddhism, however, is not its truth but its way of presenting that truth. The goal is defined negatively (and practically) as release from the transitory evils of suffering, ignorance and selfishness. Whatever has been shaped through the law of cause and effect can be reshaped by the same law. Codes of moral behavior serve principally as a preparatory discipline, a method of purification for the most important task of cultivating "mindfulness". Direct insight into the workings of the causal law in oneself is what strikes at the root of all the illusions of the ego and its suffering.

|

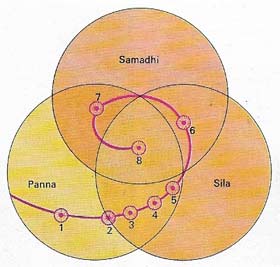

| An Eightfold Path offers the Buddhist the only way to the blissful state of nirvana – release from the external cycle of rebirth. It is based on the fundamentals of Sila (morality), Samadhi (concentration), and Panna (wisdom) and its steps are right views (1), right intentions (2), right speech (3), right action (4), right livelihood (5), right effort (6), right mindfulness (7), and right concentration (8). Several lifetimes are needed to reach nirvana |