Islamic art

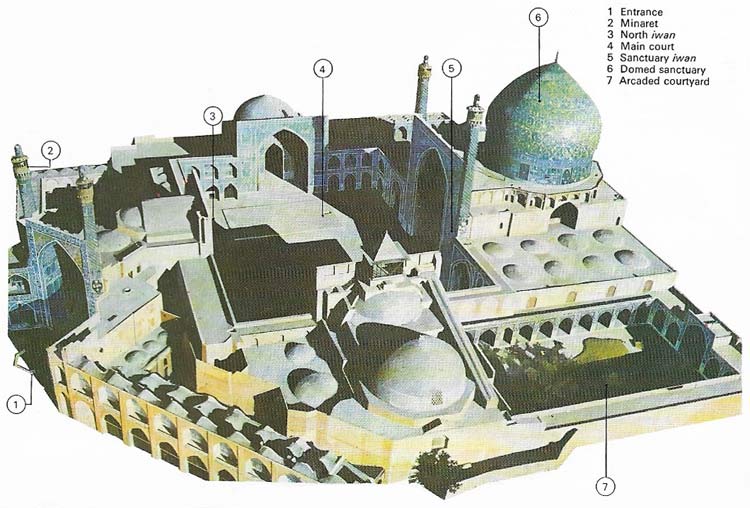

Figure 1. Glittering with polychrome tilework, the Royal Mosque Isfahan, epitomizes Persian mosque architecture with its ample vestibule, subsidiary domed prayer chambers, and two madrasas. Its principal feature is the iwan, a huge vaulted porch within a rectangular frame. The major iawns, leading into the mosque and sanctuary, display paired minarets.

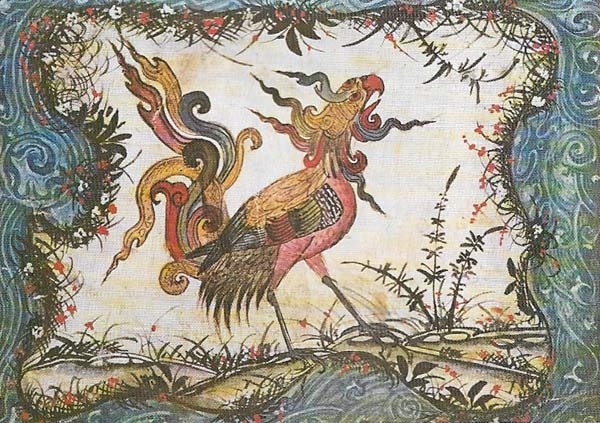

Figure 2. Painted in Iran in 1296, this bestiary page reflects the rule of the Mongols. Through their pan-Asiatic empire, numerous Chinese motifs were introduced into Persian painting – in the case the phoenix and the conventions used for feathers, plants, and border.

Figure 3. This ceramic bowl with luster-painted decoration (c. 1300) depicts a Coptic priest swinging a censer. The design was scratched with a stick and is essentially a pattern of rhythmical reciprocating curves. The double-fired technique and decoration reflects Mesopotamian influence.

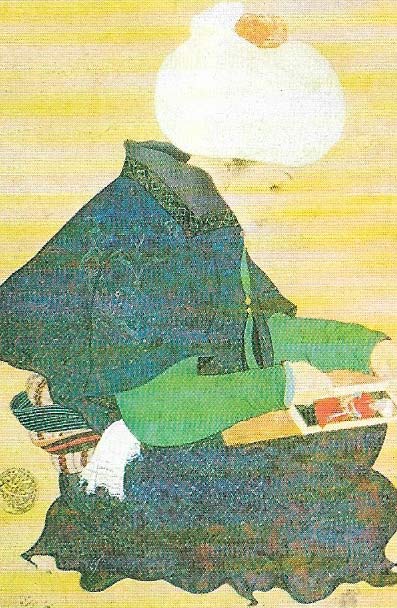

Figure 4. This late 15th-century portrait in Turkish costume was painted by Kamal Al-Din Bihzad (c. 1460–c. 1533). His use of color and compositional sense profoundly influenced Islamic artists.

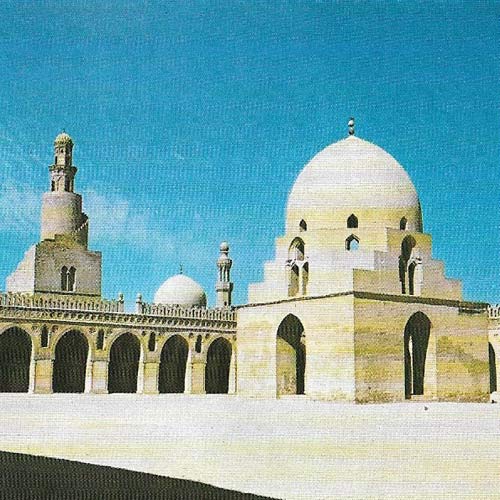

Figure 5. The Mosque of Ibn Tulun, Cairo (876–879) with its huge scale, enclosed and empty precinct, crenelated walls, spiral minaret, brick piers, and abstract stucco ornament, carried into Egypt the style of Abbasid Iraq. The arcaded courtyard with a deep sanctuary is a constant of early Arab mosques. The mosque's uncluttered spaces are in deliberate contrast to the busy city outside.

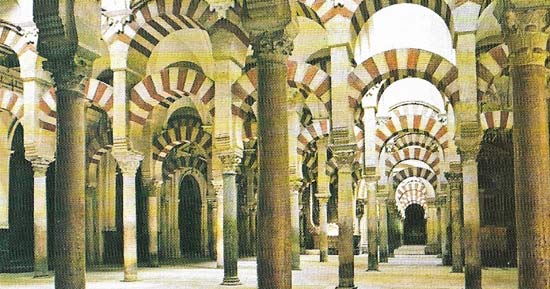

Figure 6. The frequent extensions to the interior of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain 9begun 785–786), finally resulted in a sanctuary disproportionately deep in relation to the courtyard. Endless diminishing vistas of horseshoe arches open on every side. A pitched roof covered each arched bay and to gain the requisite height the architect either placed columns one above the other or built special piers over them. This was a classical device.

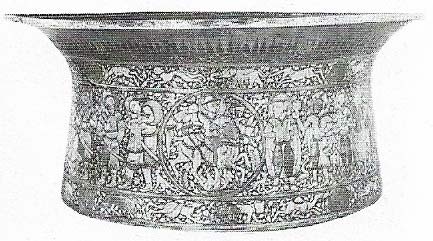

Figure 7. Inlaid with gold and silver, this bronze basin "Baptistere de Saint Louis" (Egypt or Syria c. 1300), celebrates the technical virtuosity and iconographical resources of early Mameluke metalworkers. Externally narrow animal friezes frame a broad central band with monumental scenes of courtly life; insignia or rank and heraldic emblems identify the main notables.

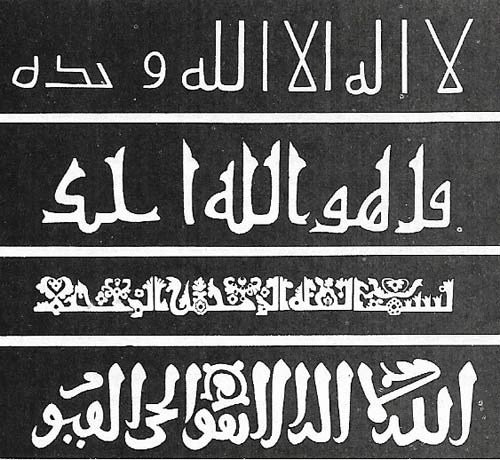

Figure 8. These drawings of angular inscriptions dating between 790 and 1543 are part of the rich repertory available to the Islamic designer. Often several scripts were used in a monument for added contrast. Extraneous ornament makes some virtually illegible, thus emphasizing their decorative function.

Architecture and its decoration best illustrates what is known as Islamic art. But the glamor of the great religious buildings has also tended to obscure the importance of Islamic secular art, which expressed itself most readily in painting, pottery, metalwork and textiles — hitherto the "minor arts"; under Islam they achieved major status.

The extent of Islamic art

Geographically Islamic art extends from Spain in the west to Indonesia in the east. It flourished from the 7th to the 17th centuries and thereafter gradually declined. Despite this wide range in space and time it has an instantly recognizable cachet. This is most apparent in Islamic decoration, which displays unequalled resource and virtuosity. The ban on the representation of living figures in a religious context — a ban that did not apply in secular art — directed the imaginative energy of the artist towards geometric, floral and epigraphic ornament such as the ubiquitous and aptly named arabesque (winding stems and leaves) and numerous varieties of Arabic script. In religious buildings Koranic inscriptions predominated and calligraphy was given special reverence (Figure 8).

In architecture the characteristic Islamic building is the mosque (Figure 1). In its primitive form it derived from Mohammed's house in Medina, which had an open enclosed courtyard with a roofed area facing Mecca. Many mosques had a minaret — a tall tower for the call to prayer. Other characteristic Islamic buildings include the caravanserai for accommodating travellers, the madrasa or theological college and the ribat, a kind of fortified monastery. Palaces and tombs abound. These various building types differ considerably from one country to the next, but they all have a number of domes; lengthy arcades with pointed or horseshoe arches; complex vaulting; open courtyards as an integral part of the design; and large expanses of flat wall surfaces decorated with carved stucco, polychrome tilework or inlaid marble.

|

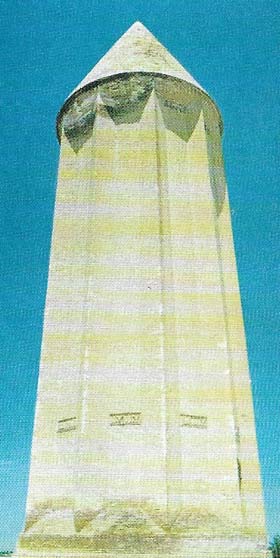

| At Gunbad-i Qatomb of a minor prince, whose sarcophagus was apparently suspended from the roof, is the first and greatest of a series of tomb towers built for rulers or saints and found throughout northern Iran and Anatolia from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Their form probably originated in central Asia and was later modified by the influence of nomad tents and Caucasian churches. |

Early Islamic art was produced mainly in Syria under the Umayyad dynasty (661–750). Umayyad religious buildings clothed Byzantine forms in glittering mosaics, while palaces used chiefly Persian motifs within a basically Roman structure. Such eclecticism remained one of the constant features of Islamic art.

Stylistic variations in Islamic art

By the ninth century a classical Islamic art had returned under the Abbasid caliphate in Iraq and spread widely throughout Islam (Figure 5). Its prime feature was carved or molded stucco using geometric and rigorously stylized vegetal motifs, endlessly repeated.

As the power of the Abbasid caliphs waned, new political groupings generated five distinctive regional styles: Hispano Moorish, Syro-Egyptian, Turkish, Persian and Indo-Muslim. In Spain the establishment of an anti-Abbasid Umayyad caliphate gave Syrian art a new lease of life, inspiring a distinctive style that spread through northwest Africa and was marked by an extreme, mannered delicacy of ornament applied to basically simple structures (Figure 6).

The Syro-Egyptian tradition produced a notable variety of religious buildings with carved stone exteriors and rather cramped interiors. Turkish architects, at first greatly influenced by the neighboring Arab and Persian styles, later responded to the challenge of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the greatest of Byzantine churches, by perfecting the Ottoman type of mosque. This has a great central dome, visually (but not structurally) shored up by tiers of half-domes, and slender, pencil-shaped minarets at the corners.

Pottery, metalwork and painting

Among the minor arts, which occasionally borrowed from China and also from Europe, Islamic pottery displayed technical virtuosity of a high order, especially in lusterware. The accent was always on color and decoration (which could be figural, epigraphic, geometric or vegetal) rather than on shape or body (Figure 3). The major centers of these arts were successively Mesopotamia, Egypt, Persia and Turkey.

Islamic metalwork, mainly in bronze, was technically extremely diverse, used a variety of shapes and favored scenes of courtly life framed by bands of stately inscriptions. Its heyday was in Persia and the Arab Near East from the twelfth to the 14th centuries (Figure 7). Metalwork was usually cast or engraved and niello, a black metallic composition, was used to fill engraved lines.

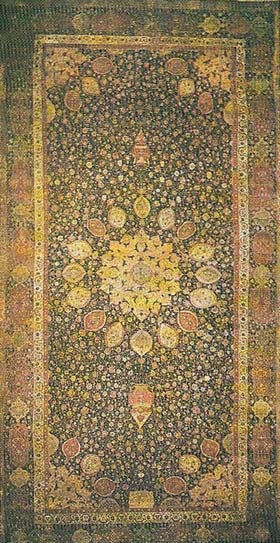

Islamic textiles fall naturally into two groups. Silks were used mainly for ceremonial and funerary purposes; most date from the ninth to the twelfth centuries and bear heraldic beasts and inscriptions. For carpets the golden age flowered in sixteenth- and 17th-century Persia. Hunting scenes and floral motifs of a complex symbolism are commonplace.

|

| The Ardabil Carpet (1539–1540), signed by Maqsud of Kashan, is 61.85 m2 (637 sq ft), giving ample room for its complex design. |

Islam has never had a tradition of easel painting, and frescoes and mosaics are also rare, but book painting has always been popular (Figure 4). Arab painting delights in animal fables, scientific treatises and genre scenes of an unexpectedly humorous quality. The mature Persian tradition (Figure 2), which influenced both India and Turkey, favored scenes from narrative poetry. Indian painting modified this by a more naturalistic approach (a rarity in Islamic art), as its portraits and crowd scenes show, while Turkish artists stressed historical subjects.