Japanese art

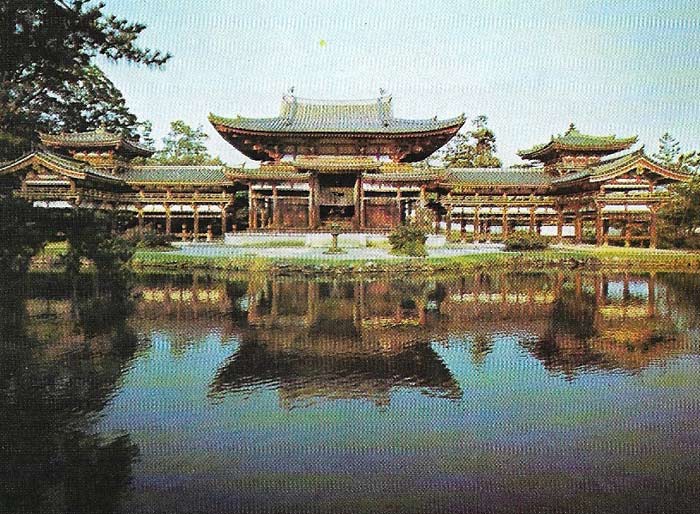

Figure 1. The Phoenix Hall of the Byodo-in, near Kyoto (11th century), was so called because it is said to resemble a phoenix settling with outstretched wings. This beautiful building demonstrates how Japanese Buddhist architects interpreted Hines ideas and retained Chinese construction methods.

Figure 2. This portrait sculpture in wood of the statesman Uesugi Shigefusa (14th century) is in a style which did not continue long. It does however demonstrate the economy of line and feature common to most later styles of Japanese portraiture. Portraits of laymen appear first in the 14th century, following posthumous Buddhist portraits of sages.

Figure 3. The Tale of Genji, a 10th-century novel, by Murasaki Shikibu, was illustrated in the Yamato-e style in the 12th century. As convention dictated, the view is from above with emphasis more on decoration than on the figures.

Figure 4. These lion dogs are attributed to Kano Eitoku (1543–1590), one of the greatest painters of the Kano school.

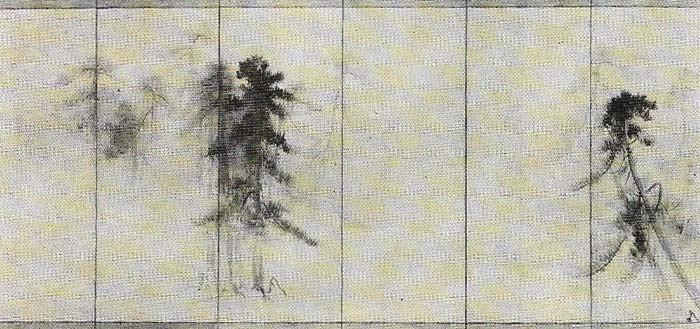

Figure 5. A screen of pine trees in a most is one of a pair by Tohaku (1539-1610), one of the contemporary rivals of the Kano artists. It shows how skill in ink was retained by artists who otherwise used brilliant color and gold leaf.

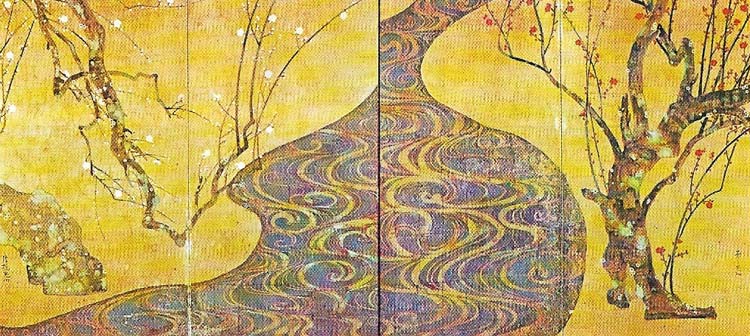

Figure 6. These screens are called "Red and White Plum Trees" and were painted by Ogata Korin (1658–1716). They are a supreme example of the Rimba or "Decorative" school of painting and they show the characteristic abbreviation of natural objects. Treating them in a conventional way in a layout that is wholly original. Yamato-e was used for simplified yet decorative effects.

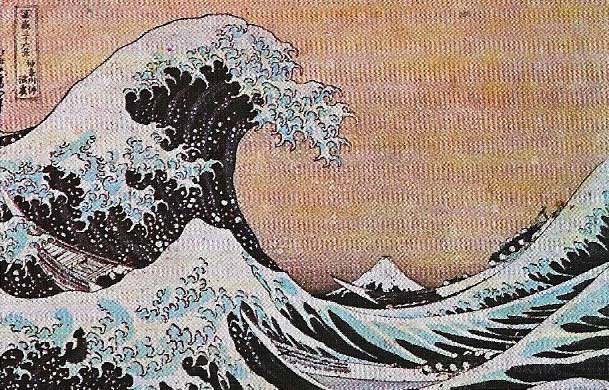

Figure 7. "The Hollow of the Deep Sea Wave" is one of a series of 36 views of Fuji in woodblock color prints by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849).

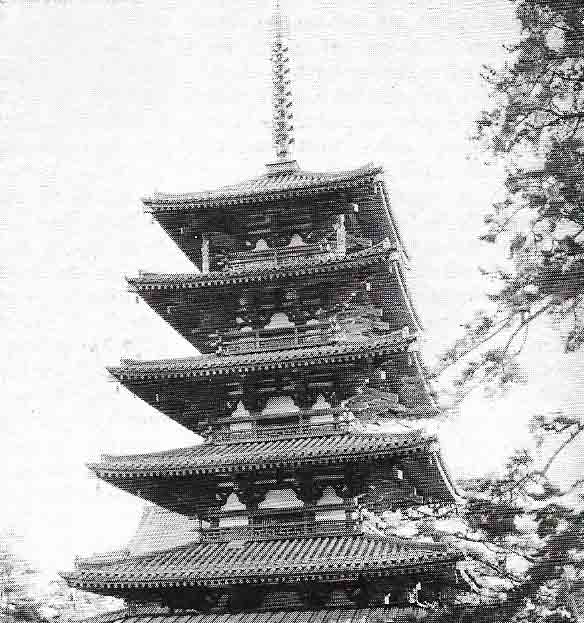

Figure 8. The Horyuji temple, Nara, is a 7th-century five-storied pagoda similar in design to wooden pagodas of the T'ang dynasty in China.

Japanese art since the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century owes much to mainland China and Korea and therefore it is sometimes dismissed as derivative. This is far from the truth, although the Japanese, always ready to absorb new influences, use imported techniques and ideas and in their own ways create new styles.

|

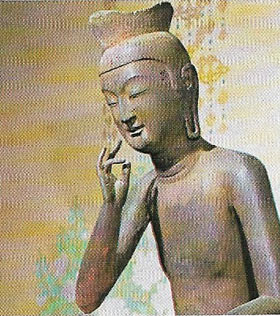

| Carved in wood, this bodhisattva (future Buddha) is 7th century and in Korean style. |

Early Japanese art

Until the 6th century Japanese art has been relatively simple but under the tuition of craftsmen from Korea, and later China, there was a burst of development in the arts and in government that led to the art of the Nara period (645–794). Much of its architecture and sculpture in wood, bronze, and dry lacquer survives in temples to this day. In the 8th-century treasure-house in Nara, the Shoso-in, quantities of lacquer, pottery and embroidery, give us a good picture of the arts and crafts of the period.

In the succeeding Heian period (794–1185) the Buddhist arts took on a more national flavour while the elegant court of the period, immortalised in the novel The Tale of Genji (Figure 3), is depicted in the famous scroll in Yamato-e style ("the Japanese style). The Yamato-e style differs fundamentally from Chinese styles in its lack of interest in the brushstroke and in its use of flat areas of opaque color.

In the 13th century there was a revival of the Nara styles in Buddhist sculpture led by the Kaikei school, and painting diversified into several groups according to the separate Buddhist sects. Secular art continued in the form of handscrolls depicting histories or satires while the handscroll format (originally a book) was also used by Buddhist artists.

Innovations from China and elsewhere

The arts flourished under the rule of the Ashikaga family during the Muromachi period (1333–1573) in spite of civil wars. Renewed contacts with China enabled painters from the Zen Buddhist monasteries to visit China and Korea and learn the art of ink-painting from Chinese painters. At first the painters' academy was exclusively filled by monk-painters. As interest in mainland culture spread, two secular schools of painters arose, the Ami school and the more important Kano school.

|

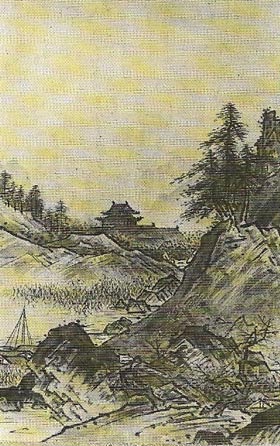

| Sesshu (1420–1506) was a painter who has visited China and learned the art of ink painting from Chinese painters. This autumn landscape illustrates how he gave a distinctive Japanese flavour to the Chinese ink style. |

The Kano school, which later became the "Classical" school in Japan, was a basically Chinese style but infused a decorative quality quite alien to Chinese scholar-painters' ideals. When in the Momoyama period (1573–1616) Kano Eitoku (Fig 4) invented the use of gold leaf as a background to screen painting in opaque color, a new unparalleled richness was introduced to Japanese art while retaining the brushstroke of Chinese convention but using Yamato-e color. This decorative effect was ideally suited to the tastes of the new military leaders who succeeded the Ashikaga; where the Ashikaga rulers had encouraged the elegance and simplicity inherent in the aesthetics of the tea ceremony, Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi wanted grandiose display. During this period the minor arts flourished as never before: lacquer, pottery and metalwork, particularly that associated with the sword and its fittings, all reached a peak of elegance. Military men prided themselves not only on their bravery and skill with the sword, but also on their ability to write verse and paint in ink.

Influences in recent times

Hideyoshi's successors, Tokugawa Leyasu and his family, ruled Japan until 1868. The Edo or Tokugawa period was one of the rigid exclusion or control of contact with the outside world in order to retain internal peace. Trade flourished within Japan, and brought with it prosperity for a new merchant class. This in turn brought a new style of painting and new ventures in the decorative arts.

The porcelain industry began in Kyushu and in the middle of the 17th century started exporting to Europe and the Near East via the Dutch, who were allowed, with the Chinese, limited trade facilities. The declining standards of the Kano school assisted the rise of a new, popular school, Ukiyo-e, the school of the print artists, who produced printed books and broadsheets, theatre posters and ephemera for the dissolute world of the Edo: their subjects were the "pop hero's" of the day, courtesans, actors, dramatic moments of plays and erotica.

|

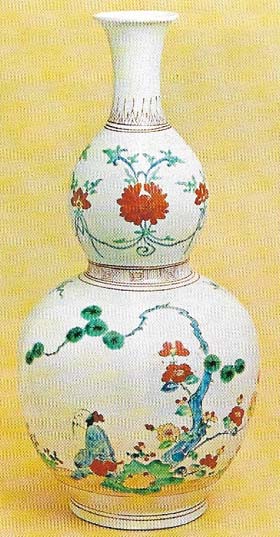

| Porcelain was exported via the Dutch from 1650 onwards. Enamemmed wares like this Kakiemon vase of the late 17th century inspired Meissen, while blue and white wares influenced earthenware design in Delft and elsewhere. |

New contact with Chinese painting introduced the scholar's style, Nanga, and subsequently two partial offshoots from this, the realist style of Maruyama Okyo and the controlled yet dashing Shijo style produced by Matsumura Goshun.

With the intrusions of the West into Japan in 1868 this activity changed abruptly. Western fashions became the rage, the court wore morning dress and top hats, painters studied oil painting in Paris, and only the intervention of such enlightened men as Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) prevented neglect or even wholesale destruction of Japan's artistic and architectural heritage. In this century there has been not only a swing back to native ideals in many of the arts and crafts but also a serious expansion into Western materials and methods, so that Japanese artists are, for instance, among the leading print makers, while such architects as Kenzo Tange are among the best exponents of a wholly international style.