Minoan civilization 2500 to 1400 BC

Figure 1. The long narrow island of Crete was the home of a Minoan civilization, the first in Europe. With much of the interior mountainous, Mt Ida topping 2,400 meters (7,873 feet), and the rugged south coast broken only by the plain of Mesara behind Phaestos, there seems little to explain civilization here. But the north coast has a gentler relief and is rich in olives and vines, and the surrounding seas encouraging trade and contact over wide areas. The Minoans actively developed their agricultural wealth.

Figure 2. Elegance of shape is even more marked in the late Minoan period from 1500 BC. The fashion changed at this time to painting in red on yellow and much greater use was made of naturalistic motifs, though some abstract elements remain. Favorite decorative subjects were flowers – lilies in particular – and sea creatures, such as octopuses, nautili, and shells among rocks and seaweed.

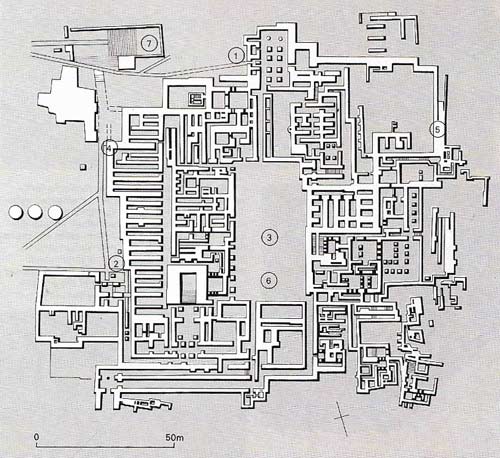

Figure 3. The Great Palace of Knossos had a long history. The plan shows it after its rebuilding in c. 1550 BC. The main entrances (1 and 2) lead by long corridors to the Central Court (3). Beneath this, deposits have been found going back to 6000 BC. Storerooms for oil and other goods (4) and for pottery (5) hint at the wealth that poured into the building, which controlled at least all of central Crete. The administrative block fronted the court on the west and faced the great staircase to the domestic quarter on the east (6). Outside the palace to the northwest, a processional way led to the theater (7).

Figure 4. A gold pendant from Mania shows the same love of nature in a very different technique. Two bees, wasps, or hornets rest on a berry or honeycomb. It is 4.6 centimeters (1.8 inches) across and is dated about 1550 BC.

Figure 5. This seal, in reality only 1.5 centimeters (0.6 inch) across, demonstrates the mastery of Minoan carvers. It is in blue chalcedony.

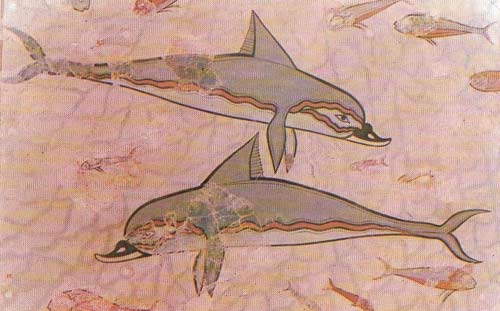

Figure 6. Fresco painting was another spectacular art of the Minoans, although it normally survives only in small fragments. This scene of dolphins and fish decorated the so-called Queen's Megaron in the domestic quarter of Knossos. Other frescoes also show birds, flowers, plants, animals, and people.

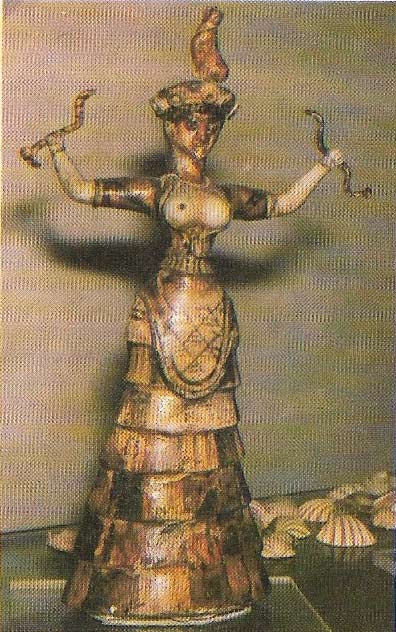

Figure 7. This pottery figurine displays a courtly elegance typical of the Minoan civilization of Bronze Age Crete. It is 29.5 centimeters (11.6 inches) high and was found in the Temple Repositories at Knossos, where it was buried c. 1500 BC. The tightly fitting bodice, open to expose the breasts, the embroidered apron and the long flounced skirt are shown frequently on seals and in frescoes. The lioness, if such it is, on her hat and the snakes in her hands are less usual and more sinister. She is probably the earth mother, whose worship is widely attested in shrines and pillar crypts on Minoan sites and in caves and hilltop sanctuaries throughout Crete.

Arthur Evans (1851–1941), the British archeologist, excavating at Knossos on the island of Crete from 1900 to 1936, uncovered a richly decorated palace, an architectural masterpiece that indicated an early civilization more distinctive and sophisticated then any other European culture hitherto discovered. Other similar palaces have since been revealed – by the Italians at Phaestos, by the French at Mallia, more recently by the Greeks at Zakro – and a balanced picture begins to emerge.

Beginnings of Minoan civilization

The Minoans (from the name of the legendary King Minos of Knossos), as Evans called the people who lived in Crete, appear mysteriously on the island at the start of the Bronze Age, about 3000 BC, perhaps as immigrants from Anatolia or, as recently argued, from Palestine. The contents of their circular tombs, most frequent on the plain of the Mesara, show that overseas contacts were maintained, contacts that gradually built up into a great trading network across the eastern Mediterranean (Figure 1).

By about 2000 BC, economic and social advance had spurred architecture to impressive achievements – the Old Palaces. Their details are much obscured by later additions and alterations, but enough survives at Knossos, at Mallia, and particularly under the west court at Phaestos, to show that building on a lavish scale was already being carried out. The implications for the social organization are of course even greater than for the technical abilities of the builders. The Minoans had achieved civilization.

One of the most obvious criteria of this is the use of writing. The earliest brief inscriptions in Crete are found on seals, where picture symbols appear to belong to a hieroglyphic script. Clay tablets found in the early palace at Phaestos show that by then a simpler syllabic writing had been devised for general use. It may well have been employed mainly for writing on some sort of paper or parchment, but such materials have failed to survive. No convincing translation of these texts, called Linear A, has yet been proposed, so its language remains unknown.

The exact nature of the island's political organization is difficult to discover. The extensive storage capacity of the palaces, for articles such as pottery as well as commodities like olive oil, suggests that they were economic as well as administrative centers, controlling territories within the island. Yet these territories had apparently nothing to fear from each other – there are no walled defenses and few signs of weapons or soldiers. Knossos clearly held a leading position, perhaps by controlling overseas trade.

|

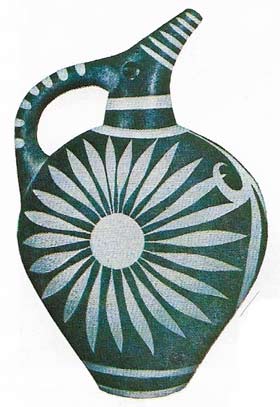

| Minoan pottery, after a long and un-spectacular development, achieved pre-eminence first in the Kamarais snare of c. 1800 BC. This is wheel-made in elegant shapes, some cups being extremely fine. The studs on the back of this jug from Phaestos suggest the handle-rivets of a metal prototype, as does the shiny black slip. The painted decoration however – the bold, curvilinear, abstract design – could come only from a ceramic tradition. |

Height of Minoan culture

Demonstrated by finds of Minoan pottery from as far away as Egypt, by colonies on several Aegean islands, and by the permeation of the mainland culture, overseas trade goes far to explain the wealth of Crete at this period. But Minoan civilization cannot be explained as simply imported from abroad: it is far too individualistic for that. After apparently natural disasters in about 1700 BC, the palaces were lavishly rebuilt and it is the ruins of these that can be seen today. Building was in limestone, within a timber-frame construction. This added a useful, if not always effective, resilience against earthquake shock, to which Crete is prone, but also added to the fire risk. Ranges of rooms opened on to the great central courts, with well-planned light wells to illuminate inner suites of chambers. Internal walls were plastered and often gaily decorated with the most elaborate and colorful frescoes (Fig 6). Floors were frequently paved with alabaster slabs. But it is perhaps the drainage system, as advanced as any before the 18th century AD, which causes the most surprise. The overall impression is a convincing one of light, air and freedom – so, different from that of the contemporary civilizations farther east and so much closer to modern ideals.

|

| This magnificent stone libation vase comes from the palace at Zakro, destroyed c. 1450 BC. It shows a sanctuary (center, left) on a mountain peak, with wild goats on the roof. A bird flies past two pairs of horns used at consecration. |

The art fully bears this out, whether it is a life-sized figure painted in the frescoes, decoration on the magnificent pottery (Figure 7), or minute detail on the carved seal-stones (Figure 8). The color and naturalism hold an immediate appeal to the modern world.

|

| On this seal impression, measuring 2.1 centimeters (0.8 inch) across, two equestrian acrobats perform in a field full of flowers. |

This great civilization's end is even more hotly debated than its origins, if only because there is so much more evidence on which to base the story. The most widely accepted version, but by no means the only one, would start from the cataclysmic eruption of the volcanic island of Thera, a little over 100 kilometers (63 miles) from the north coast of Crete, about 1450 BC. Much of Crete would have been plastered with poisonous ash, shattered by the shock waves of the explosion and pounded by monstrous tidal waves.

Decline and conquest

Of the major sites, only Knossos appears to have recovered from this destruction and here there are many signs of a profound change. The new rulers were warriors who used the Linear B script, now recognized as an adaptation of Linear A for writing an early version of the Greek language. This would all seem to point to a conquest of the island by mainlanders, Mycenaeans, who had seized the opportunity given them by the eruption of Thera to oust the Minoans from their control of the profitable sea-routes. Metropolitan Minoan was replaced by provincial Mycenaean and the palaces were lost to sight and memory.