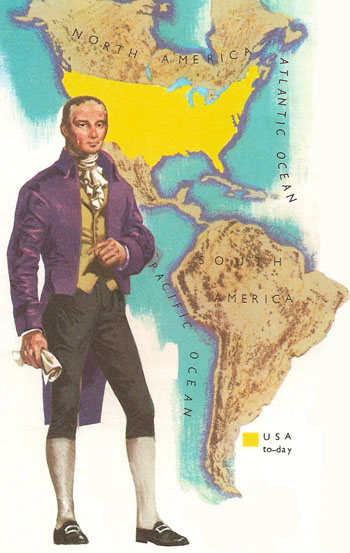

Monroe, James (1758–1831)

"I have called the New World into existence to redress the balance of the old." When George Canning, the British Foreign Minister, boastfully addressed the House of Commons in 1826 he claimed to have weakened 'Old World' Spain by recognizing the independence of those colonies in South America which had revolted against Spanish rule.

But Canning was not the first to take this step, and indeed the New World was already very much in existence. Three years earlier the fifth President of the United States, James Monroe, had made an astonishing declaration in which he denounced any form of European interference in the affairs of the entire American continent. And he had recognized the independence of Gran Colombia, Buenos Aires, Mexico, and Chile from their Spanish masters.

From rebel to President

James Monroe was born in Virginia on 28 April 1758. His father was of Scottish and his mother of Welsh descent. He went to college at the age of 16, but in 1776 he joined the army to take part in the struggle for independence which had broken out against the British. Thus at an early age he was fighting to remove the foreigner from American soil.

The War of Independence ended in the defeat of the British, and in 1780 Monroe began to study law under the future President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. Two years later he was elected to the Virginian House of Delegates, and at the age of 24 became a member of the Governor's Council. In 1790 he entered national politics as a member of the United States Senate.

Monroe held many posts in the United States government, including those of minister to both France and Great Britain. Above all he became the chief negotiator in attempts to acquire the territories of Louisiana from the governments of France and Spain respectively. Louisiana was purchased in 1803, but Florida did not become finally independent of Spain until 1821.

At the beginning of the 19th century many foreign countries had possessions in both North and South America. The British had been thrown out of the United States during the War of Independence, but they were firmly entrenched in Canada. Both Spain and Portugal had possessions in South America, while Spain, as we have seen, also owned Florida. Louisiana belonged to France. Even Russia was threatening to establish a colony in the extreme northwest of America.

James Monroe quickly became an acknowledged leader in the fight to prevent America from becoming a pawn in European politics.

In 1811 he became Secretary of State, which made him responsible for foreign affairs, and in 1814, when war broke out between the United States and Great Britain, he became Secretary for War. In 1816 he was elected to the Presidency of the United States, and four years later was re-elected with every electoral vote except one cast in his favor. That one vote was cast for his opponent in order to preserve for George Washington the honor of being the only unanimously elected President.

After his retirement from the Presidency in 1824, Monroe's later years were marred by growing poverty. He was compelled to ask the government for a grant to help him settle his debts. He died, appropriately enough, on Independence Day, 4 July 1831.

Go home, Europeans!

On 2 December 1823, James Monroe made the famous declaration since known as the Monroe Doctrine. This declaration applied the principles of independence from European colonization and interference not only to the United States but to the entire continent of America. The message ran: "We owe it therefore to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety."

Apart from the compromise reached over the British Colony of Canada, the Monroe Doctrine has been a guiding influence in the policy of the United States for well over 150 years. It meant that the government of the United States would regard any attempt by foreign powers to acquire influence or possessions anywhere in America as a threat to herself; and she would oppose that threat. It did not mean that the United States considered she had a 'protectorate' over the other independent countries of America.

This has always been carefully stressed by United States Presidents. When the United States opposed French intervention in Mexico in 1867, she made it clear that once the French were out there would be no more United States interference in that country.

But this high-principled doctrine had its dangers. It resulted in the United States' isolation from Europe in the 1920s and '30s, for if the United Sates forbade Europeans to interfere in the Americas, she herself had no right to interfere in Europe.

When the United States forced the Soviet Union to dismantle her missile bases in Cuba in 1962 it was with the Doctrine of James Monroe very much in mind.