myth

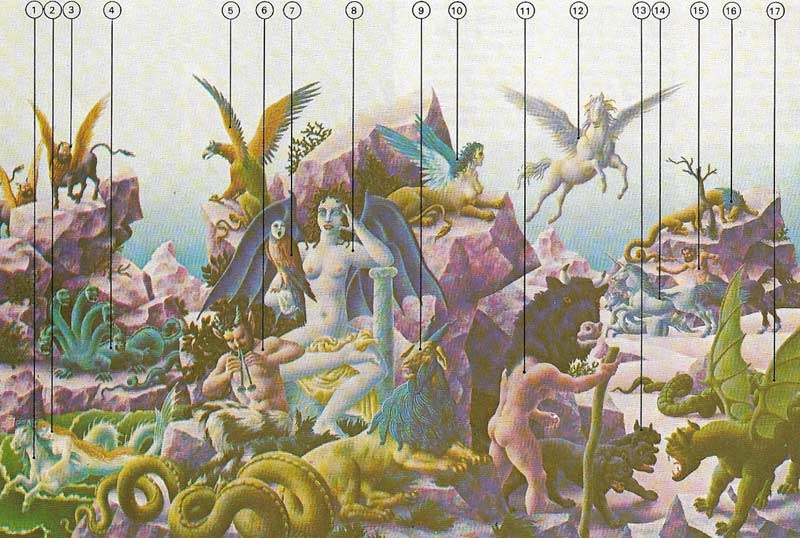

Figure 1. Fantastical creatures play an important part in many myths, probably be-cause they appeal to man's need for the unusual and to his awe of the forces around him. The fire-breathing Chimera (9), for instance, expresses the power of the volcanoes it inhabits. The creatures and events of myth may also be shadows of actual events. Hercules' struggle with the Hydra (4) may mirror the draining of the marshes by some former king; while the Centaurs (15), half-horse, half-human, may have originated with the famous horsemen of Thessaly. Others pictured are Hippocampus (1), the Mermaid (2), the winged Lamassu (3) of Babylon, the Gryphon (5) from Asia, the Satyr (6), Sirens (7), Medusa (8), the Sphinx (10) from Egypt, Minotaur (11), Pegasus (12), Cerberus (13), the Unicorn (14), La Tavasque (16), and the Dragon (17)

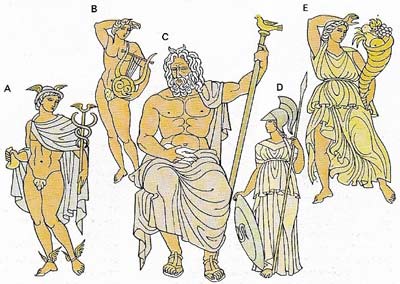

Figure 2. Myths create gods in the form of man. This anthropomorphism was at its height in ancient Greece where the gods expressed in extreme form human qualities such as beauty, anger and love. Shown here is part of the Greek pantheon. Hermes (A) was the messenger of the gods, Apollo (B) was patron of music and Zeus (C) was the ruler of all the gods. Athene (D) was protector of Athens and guardian of the crafts. Demeter (E) was a fertility goddess, often associated with corn.

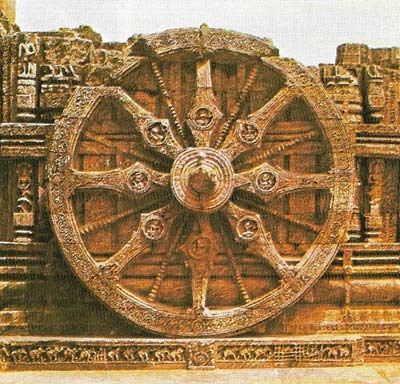

Figure 3. This 13th-century Hindu wheel at Konarak, India, symbolizes the circular nature of the universe. The unending cycle of birth and death is a stock element in mythology. The couple, male and female, will always be there creating new generations. The idea of no birth without death signifies the eternal cycle to which Hinduism and Buddhism subscribe in different ways; the former aiming at the perfection of life, the latter at its renunciation.

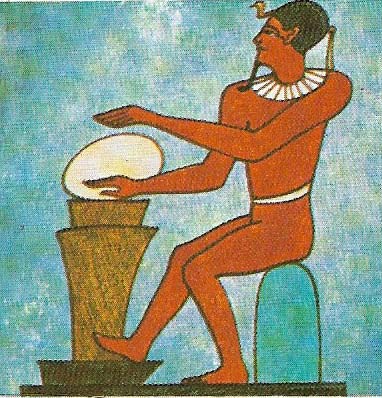

Figure 4. One version of Egyptian creation myths has Ptah of Memphis shaping the world, in the form of an egg, on a potter's wheel. But it was also he, the creator of all things, who dwelt in the egg while it was in the primeval waters. The image of the world egg appears in other mythologies; that Phanku, in Chinese mythology, holds the egg of chaos, composed of the yin and yang (female and male) symbols, out of which he was born.

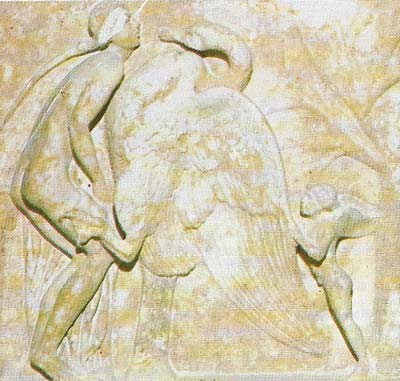

Figure 5. This Roman relief of Leda and the swan depicts one of the love stories in which Zeus couples with mortal women. The transformation of gods as well as mortals into animal form is a common mythological theme. Swans are held to be sacred birds in many places, and killing them is believed to bring misfortune.

Figure 6. Anubis, the jackal-headed Egyptian god, like the Greek god Hermes, conducted souls into the underworld. Here they would be judged by Osiris while Anubis assisted by weighing the heart. He was guardian of cemeteries and may have been deified so as to prevent jackals from devouring the dead. After Osiris had been dismembered by his adversary Seth, Isis enlisted the help of Anubis, who was also the embalmer, to reassemble her husband's body, so creating the first mummy.

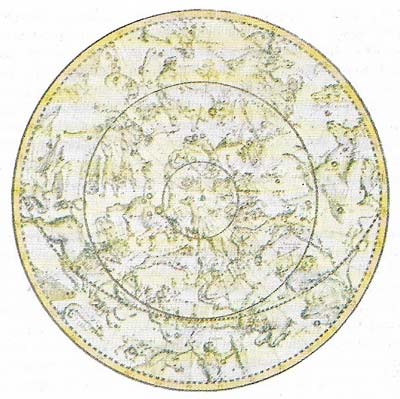

Figure 7. This 1790 Italian map shows the stars visible from Earth's Northern Hemisphere, grouped together by constellations whose symbols date back to a time when man's observations were influenced by the concepts of Greek mythology. The periphery is formed by the Zodiac. The Zodiacal signs indicate months.

Myths are tales or traditions that seek to explain the place of man in the universe, the nature of society, the relationship between the individual and the world that he perceives, and the meaning of occurrences in nature. Today we tend to draw a sharp line between facts that can be proved scientifically and beliefs and ideas that cannot be so proved. These latter are often lumped together and dismissed as "imagination" or "inventions" or "myths". This spurious contrast between myth or fantasy on the one hand and "hard facts" on the other conceals and distorts the value and significance of myths as guides to life.

Myth, science, and religion

Myths are found in every part of the world and, despite their bewildering variety, share certain common characteristics (Figures 1 and 5). These similarities arise because men everywhere face the same basic problems and ask the same questions. They want to know why they are what they are, why nature behaves as it does and how cause and effect are linked. It is human nature to seek for meanings as well as causes for everything that arises in consciousness.

|

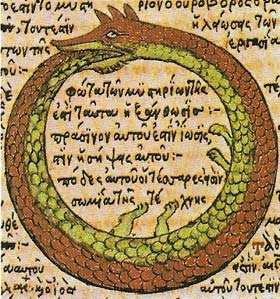

| The snake or dragon that eats its own tail forms a circle signifying the cyclical nature of all things (a common mythological theme). This illustration from a 15th-century alchemical text bears a color-coded message; green (faded) for the beginning, red for the goal of alchemy. Tail-eating creatures are found in myths from all over the world. A Japanese map shows a tail-eating snake whose movements under the earth are said to be the cause of earthquakes. |

|

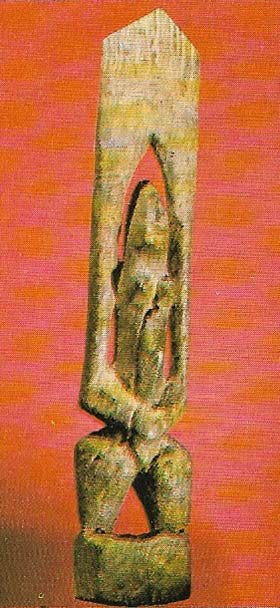

| Hermaphroditic statues, such as this ancestral Nomo figure from Mali, are found the world over as part of the common preoccupation with fertility. Fertility rites may take the form of a sacrifice to ensure new life, or, as here, be fundamentally magical; bisexual figures can fertilize themselves, so guaranteeing offspring. The worship of such statues was expected to result in the fertility of land, animals, and humans. Some carvings from Africa and Oceania are divided, showing a male and a female half. |

Although science has now answered many of the "how" questions, the reasons "why" – man's relation to the cosmos and the nature of the life-force within him – remain basically unanswered and unanswerable. Myths have in common with religions the fact that they both offer reasons as well as causes; both the "how" and the "why" of the universe. By comparison with many world religions, however, most myths are less concerned with direct guidance. They contain an implicit moral, but their main aim is not to impose it. They are "just so" stories concerned with explaining the unquantifiable aspects of existence and deal with both common human experiences and with the supernatural.

From the mythological standpoint the world we experience directly is not the only world. The phenomenon of birth can be understood as a physical process but that does not exclude it also being regarded as a supranatural event (for example, as a reincarnation). Indeed most people will admit, if they are truthful, that they actually experience life on two levels – the scientific and the mythological. But in our increasingly literal-minded, science-dominated society it is only in extreme situations – where the rational fabric of society breaks down – that our mythological consciousness surfaces.

The mental processes behind mythology

The step-by-step logical thinking required for the acquisition of scientific knowledge is slow and laborious. It is much easier to arrive at conclusions by comparisons and analogies where "just as . . . so in" are the key words.

Myths explain the phenomena of nature, for instance, by drawing parallels between simple, known things and those that are harder to grasp. Fire has something in common with the sun, the source of heat and energy. Gold is shiny and resembles the sun in color. It also does not rust with weather and therefore signifies immortality. So out of common physical characteristics, symbolic equations are made and one thing takes on the qualities of another.

As the egg originates life, so the world was created out of an egg (Fig 4). Mountains are often inaccessible and inspire awe, as do the beings that man credits with having more power than himself. So the proper habitation for the gods may be a mountain, such as Mount Olympus, abode of the Greek gods. Thunder and lightning inspire fear as do outbursts of anger; hence a man killed by lightning must have offended Zeus, the chief Olympian (Figure 2). Sometimes one characteristic is made use of in the equation, sometimes another. As thunder ushers in rain, so, where rain is scarce, thunder may symbolize fertility. Rivers, trees and animals, all have their characteristics, expressed in terms of such human values as cunning and fertility, destructiveness and courage.

The necessity of myths

But myths do not just explain why man and the world in which he lives are as he finds them. This view of mythology would be inadequate. Image-making is one of the most distinctive human characteristics. The telling of myths becomes a vital necessity not simply to placate or propitiate the suprahuman powers, but to stimulate the very same creative and spiritual gifts that made man invent his myths. Without meaning and purpose beyond the satisfying of the daily physical necessities no man and no culture can flower. By the same token man needs an understanding of his defeats and victories, of birth and death, in order to stave off the despair that the vagaries of fortune and the complexities of life might induce. There is, accordingly, a myth to answer almost every mood and question. There are myths of origin or creation, of fertility and heroism, of resurrection and immortality.

Myths are timeless and perpetual in the sense that man's need to live in harmony with his nature by means of guidelines (which we now call psychological rather than spiritual or religious) is as great as ever. Myths provide a bridge between outer "realities" and the hopes, wishes and fears of our dreams. They provide man with comfort and support. In them he may find a play area in a world which would otherwise be fearsome, unbearable, dull or frustrating. Such play is as necessary as our daily work.