the novel and press in the 19th century

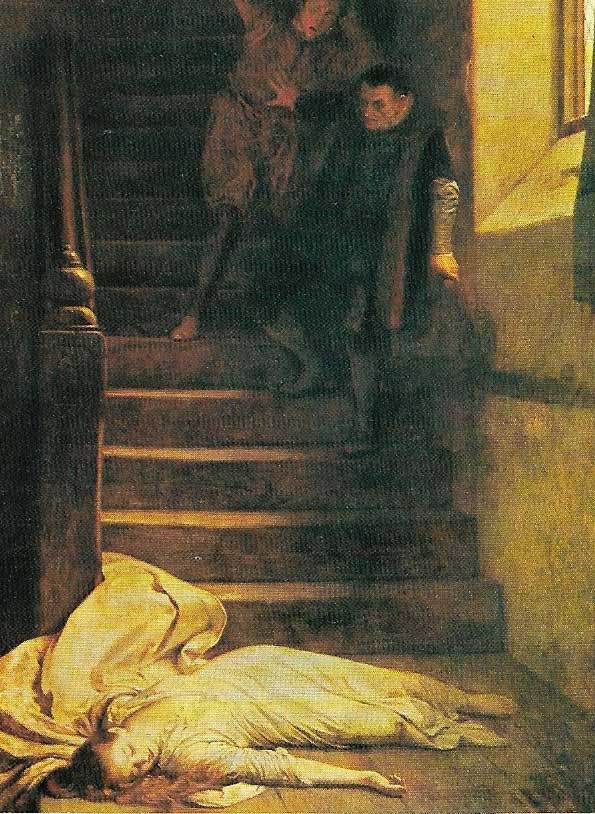

Figure 1. Scott's novels are full of dramatic incidents, such as Amy Robstart's death in Kenilworth. His success with historical romance was huge. He built a country house with the proceeds, went bankrupt and wrote himself out of debt. Much of his writing is slack and he is no longer widely read, but his greatness is unquestionable. His use of famous historical characters is discreet: they are rarely central and his sense of how history bears on the experience of ordinary people has a breadth and humanity declared Shakespearean by his European admirers.

Figure 2. Dickens's novels were published in frequent illustrated instalments, as with Nicholas Nickleby, the parts of which are shown here. Part-publication was common practice and allowed Dickens to keep in close contact with his public and alter plots if sales fell off; he kept the English-speaking world in agonised suspense over the death of Little Nell in the Old Curiosity Shop. Dickens was, however, a serious artist who influenced, among others, Dostoevsky.

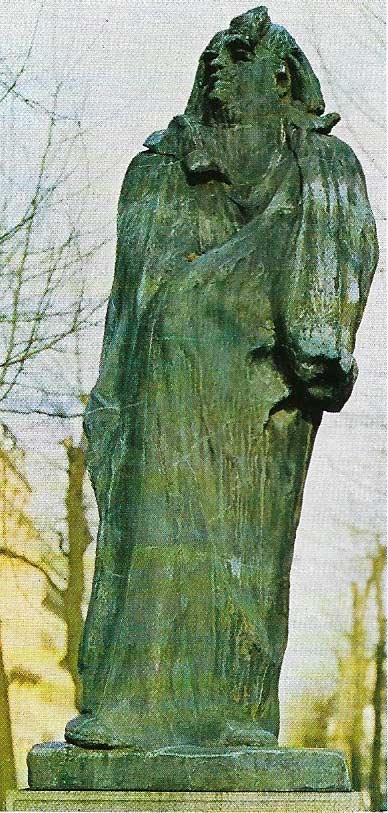

Figure 3. This remarkable sculpture of Balzac by Rodin suggests the bulk and force of Balzac's vision of human society. His 85 novels attempt to characterise almost every aspect of life in France between the 1780 revolution and the fall of Louis Philippe in 1848. By romantic standards an unrewarding subject for the novelist, but he made it lively and real.

Figure 4. Germinal, Emile Zola's outspoken novel describing conditions of life endured by miners in northern France, illustrates the freedom from prudery that French novelists enjoyed. Mrs Gaskell, Kingsley and Dickens had tried to depict the consequences of industrialisation without dealing with human sexuality.

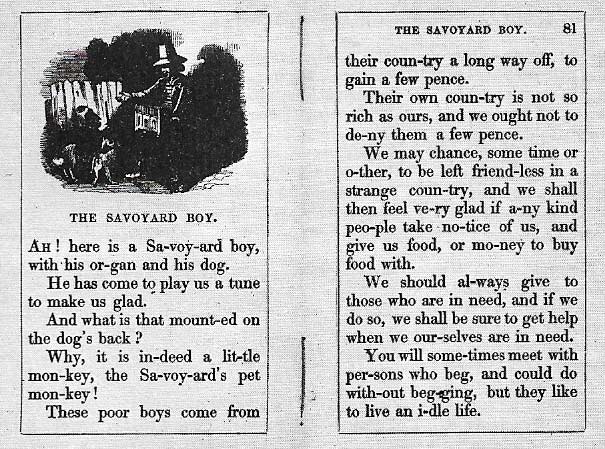

Figure 5. Green's Universal Primer injected heavy-handed moralising into reading lesions. Urban, but not rural, literacy rates were fairly high in the 1840s. Total illiteracy ranged from 16% to 25% and about three-quarters of the working class was literate by the middle of the century. Most people read only "novels of the lowest character" and fears were expressed about whether "good" literature could survive.

Figure 6. Emile Zola in Les Rougon-Macquart attempted to follow the adventures of a family during the 1880s, calling it "a physiological history of the 2nd Empire". The series has 20 volumes with modern themes: in The Dram Shop (1877) the evils of drink; in Nana (1880) sex; in Earth (1888) the deadening brutality of peasant life. Naturalists believed writers should go beyond the surface detail of life.

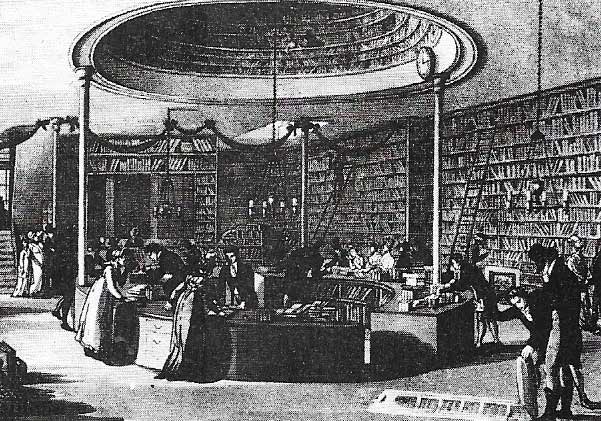

Figure 7. The Temple of the Muses in Finsbury, London, was a rate-supported "public" lending library. Novel-reading was widespread in middle- and upper-class households by the middle of the 19th century. In Britain even the wealthy subscribed to circulating libraries. Consequently a novel's success or failure depended on the good will of these libraries, which had a vested interest in keeping books both expensive and "pure". "Society will not tolerate the natural in our art", complained Thackeray in his novel Pendennis (1848). But the libraries were not so easily resisted.

There were many technical innovations in printing between 1800 and 1900 that had important effects on newspapers and novels. The use of metal presses, steel engraving and, after 1848, of stereotypes and mechanical presses completely altered the production process. Marketing techniques changed too: circulating libraries (Figure 7), railway station bookstalls and cheap reprints of successful titles helped to establish and satisfy a market that expanded with the rising population, increased literacy (Figure 5) and greater educational opportunities. In Britain, newspapers were hampered by taxation until 1855, but by the end of the century mass circulation newspapers had developed.

Changes in the novel

The novel never suffered taxation problems but was otherwise similarly affected by these changes. The huge problems of the new industrial cities offered fresh subject-matter to be interpreted in the new intellectual climate of Europe after the French Revolution. Even two such early novelists as Jane Austen (1775–1817) and Walter Scott (1771–1832) (Figure 1) reveal a distinct if conservative responsiveness to change. Jane Austin's domestic comedies, carefully structured in six novels, are at once amusing and deeply serious. Scott virtually invented the historical novel. His popular success brought him a considerable personal fortune.

|

| Jane Austen concentrated on witty, incisive descriptions of rural English society. Her sense of form had its roots in the classical English comedy of Congreve and Jonson. She was the first of a remarkable line of women novelists whose lives were otherwise provincial and obscure. During her lifetime she earned only £250 for six novels, but time has discriminated in her favor and she is now regarded as an immortal of English literature. Two of her best works are Pride and Prejudice (1813) and Emma (1816), both about ordinary people unaffected by world events. |

Popular success was also enjoyed by his Victorian successors William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–1863), Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) and above all by Charles Dickens (1812–1870) (Figure 2) and George Eliot (1819–1880). Dickens built up an astonishingly close relationship with his readers in his sentimental but brilliantly funny and sometimes despairing vision of city life. George Eliot, on the other hand, was provincial in her subjects and European in the range and discipline of her thought. The mid-century also saw the publication of the Bronte sisters' novels. Charlotte (1816–1855), author of significant poems as well as of the novel Wuthering Heights, has since been more highly regarded. Important later novelists include George Meredith (1828–1909), George Gissing (1857–1903), Samuel Butler (1835–1902) and Thomas Hardy (1840–1928). Hardy's novels frequently express a passionate feeling for man's tragic involvement in nature and estrangement from it.

|

|

| Mass circulation newspapers became possible after the development of new printing techniques and the ending of the newspaper tax in 1855. Serious, major journalistic innovations, like The Times' coverage of the Crimean War (top), probably had less influence on novels than "gutter press" sensationalism (bottom). |

The novel in Western Europe

French fiction in this period was much more urbane and less prudish than English. The realists, Stendhal (1783–1842), Honore de Balzac (1799–1850) (Figure 3) and Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880), depicted French history and bourgeois life at a great length and in minute detail. Romantic experience and attitudes, however, were given vivid expression in the works of Victor Hugo (1802–1885) and George Sand (1804–1876). Emile Zola (1840–1902) (Figure 6), leader of the naturalists, produced franker and more painfully pessimistic studies of the workings of heredity and environment in human affairs (Figure 4). The enormous popular success of Alexandre Dumas the father (1802–1870) and his historical romances were matched by that of his son of the same name (1824–1895).

The giant figure of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) overshadows nineteenth- century German literature. In his wake the regionalist anti-romanticism of Theodore Storm (1817–1888) and Fritz Reuter (1810–1874) seems relatively less significant. Italian prose in this period was dominated not by one great man but by one great book, The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni (1785–1873), a patriotic Romantic who was greatly influenced by Scott. The task of modernizing the Italian novel fell to Giovanni Verga (1840–1922) and Antonio Fogazzaro (1842–1911).

The literary tradition in Russia

In some ways the most surprising national achievement in the evolution of the novel was that of Russia. The first major Russian novelists were Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841) and Nikolai Gogol (1818–1852); their successors, Ivan Turgenev (1818–1883), Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) and Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) were to make a deep impression on Western European culture when their works were translated into French, German and English. Tolstoy's War and Peace and Anna Karenina are among the greatest of all literary works.

|

| Tolstoy's funeral was the first non-religious Russian funeral, yet he died with the reputation of a saint because of his religious and political devotion to the ideal "simple peasant" life. In What is Art? (1897) he had repudiated most of European literature including his own and Shakespeare's works, yet in his own ascetic and prophetic old age he demonstrated the same sort of passion and contradictory idealism with which he had invested his fictional heroes.. |

While Dostoevsky's intellectual perspectives are significantly modern it was Henry James (1843–1916) who introduced modern techniques into the novel. Although he spent most of his life in Europe, he remained in important ways American. The formal complexity and ironic indirectness of his work is also characteristic of Nathaniel Hawthorne (1806–1864), Herman Melville (1819–1891) and Mark Twain (1835–1910). In his own fiction James abandoned the convention that the author knows everything and selected one or two characters from whose point of view he told his story. Although most of his own novels are long, this technique led on to the writing of shorter, more economical works. As well as the artistic reasons for this development there were also strictly commercial ones: with the advent of cheap editions that readers could buy for themselves the great circulating libraries were in decline and publishers became less interested in length alone. The age of the Victorian novel was over.