Offa

Offa is chiefly remembered for the great dyke between England and Wales which still carries his name. The Welsh were a great nuisance to Offa; they were always sneaking down from their mountains and slipping into the kingdom of Mercia to steal cattle or to make other forays, so Offa determined to stop them. He dug a great dyke, very high on the English side, and very deep, which stretched from the mouth of the river Wye in the south to the river Dee in the north. It is still the dividing line between England and Wales and Welshmen coming to England even today talk of 'crossing Offa's Dyke'. The remarkable thing is, that after centuries of plowing and cultivation of the land, parts of the dyke are still visible at the northern end in Flintshire and are often pointed out to tourists. If you look at a map of England and Wales you will see there is a gap in the mountains round about the towns of Shrewsbury and Oswestry in Shropshire which made it very easy for the Welsh to make lightning raids into the very heart of the kingdom of Mercia, but the gap works both ways for in later centuries it has provided a path along which many English influences have penetrated into Wales. Offa's Dyke was a major engineering achievement and it was very effective, not only as a physical barrier but as a symbol and there are many references to it in the border literature of both countries.

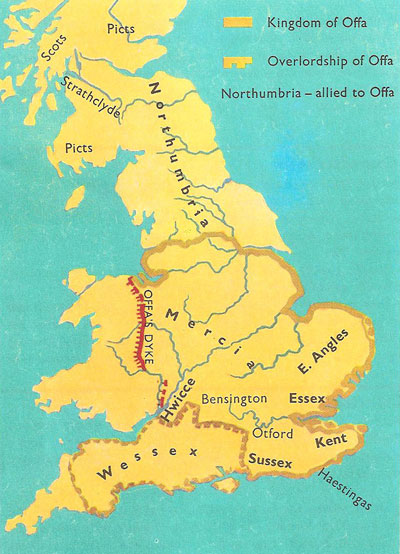

At the time when Offa was king, from 757 to 796, Britain was made up of several small kingdoms of which Mercia was the largest; it covered roughly the area between the Thames and the borders of Northumberland. Offa, who is often called Offa the Great, is remarkable because he is the first king who appears to have had the ambition to unite all the kingdoms of England and make them into a strong country. He was always trying to take over the other kingdoms, not always by war but by agreements and alliances through marrying his sons and daughters with sons and daughters of other kings; this way he could get more and more kingdoms under his control. He eventually became very powerful and was able to make treaties on equal terms with the great Charlemagne, the king of the Franks, who at that time was the most powerful king in the western part of the world.

Many of us today know very little about the eighth century English Kingdom of Mercia and its great King Offa. We know much more about Alfred, King of Wessex, who reigned a hundred years later than Offa.

A reason for this is that one of our chief sources for these distant times is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It was begun in Wessex and the men of Wessex were mostly interested in recording their own deeds rather than those of another kingdom. The Chronicle tells us little about Offa. Of his death it merely says: 'In this year Offa, King of Mercia, passed away on August 19; he reigned for 40 years'. As we shall see, Offa deserves greater mention than this.

Sources for Offa's reign

Apart from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which gives the most meager information about Offa, our main sources today are some lives of Saints and several hundred landbooks, which are documents recording the buying and selling of land.

Offa compiled a code of Mercian laws. These have, unfortunately, been lost, but we know that Alfred used them later when he drew up a code of laws for Wessex. It is also very sad that the Venerable Bede, whose writings tell us so much about the Kingdom of Northumbria in the seventh century, should have died before Offa's reign began.

Offa's achievement

Offa reigned from 757 to 796. When he became King, England was made up of several small kingdoms, of which Mercia was the largest. The king who ruled over Mercia before Offa was called Ethelbald (716–757). So for a period of 80 years, Mercia only had two kings, This was most unusual for a time when the lives of kings were short and dangerous. For instance, Northumbria had eleven kings over the same period.

Ethelbald did a lot to extend the kingdom of Mercia; in his day he was called 'King of the Mercians and South Angles'. Offa, who was Ethelbald's third cousin, was referred to by the middle of his reign in Latin charters as 'rex Anglorum' (King of the English) and 'rex totius Anglorum patriae' (King of the whole land of the English). This was by no means an idle claim.

Offa is often called Offa the Great. He seems to have been the first English king to have had the vision and the ability to unite all the little English kingdoms and make them into a strong country. How did Offa set about enlarging his kingdom and making it strong and respected? The answer is by fighting, by agreements and alliances with other kings, not only in this country, but also on the continent.

There were not, however, many battles in Offa's reign. The most important were at Otford (774) where he defeated the men of Kent, and at Bensington (779) in Oxfordshire where he defeated the men of Wessex. In 778 Offa devastated South Wales and in 793 Offa killed the king of the East Angles and annexed his kingdom. Offa either swept away the little kings or they became vassals. We know that the kings of Kent and Sussex witnessed landbooks as his vassals. He deposed the sub-kings of Essex and the Hwicce.

Royal marriages

Offa believed as much in the importance of alliances as of war. For example, he married one of his daughters to the king of Northumbria and he never had any trouble with that kingdom. Another daughter he married to the king of Wessex after the battle of Bensington. Even Charlemagne, king of the Franks and the most powerful ruler in the western world at that time, agreed to marry his daughter to one of Offa's sons. This shows that Offa came to be regarded as the important King of an important country.

Encouragement of trade

|

| A coin of Offa's time |

Offa encouraged trade with the Franks and with other countries farther afield and for this purpose he reformed the coinage in England. At this time there were almost no coins in England. The people lived mainly by what they grew and kept animals for their meat, their leather and their wool. When they wanted to buy anything, they had to do it by exchanging ,by what is called barter. They had almost completely forgotten the idea of money. But barter is a very cumbersome way of buying and selling; so eventually they revived the idea of using for exchange objects which everybody values – just as we use coins and notes today.

Then as now, gold and silver were thought to be specially valuable. Ladies liked to have gold and silver ornaments. In early days the Anglo-Saxons used such coins as they found or made mostly as ornaments. It was in Offa's time that coins were first used at all commonly for buying and selling. Gold was very rare and very expensive and so the first coin was the silver 'penny'.

From Offa's time right down to the thirteenth century the silver penny was almost the only coin used in England. With a silver penny one could buy far more than with a modern penny; it was worth perhaps as much as 30 dollars today.

So Offa struck some gold and silver coins; one of his gold coins still exists and you can see a picture of it on this page. It was probably made to trade with the Arabs in Spain.

Offa and the church

Offa was a generous benefactor of religious causes. He founded St. Alban's Abbey in Hertfordshire, and once went on a pilgrimage to Rome.

He wanted to create a new archbishopric, which would be independent of Canterbury. Pope Hadrian 1 sent a delegation to England in 786 to discuss this question. They agreed and the new archbishopric of Lichfield was founded. In return Offa agreed to make an annual gift of money to the Pope. This is thought to be the origin of Peter's Pence. In 803, seven years after Offa's death, this scheme of a new archbishopric was abandoned. It was not until the reign of Edward the Confessor that the Pope sent another delegation to England.

After Offa

By the end of Offa's reign 'England' had emerged as a political fact. Most of the kingdoms of England acknowledged him as their overlord. But when Offa died, the power of Mercia soon collapsed and in the tumult of the Danish invasions, which followed in the 9th century, power moved south again – to Wessex.

Offa's son was a delicate youth who died 141 days after his father. He was succeeded by Coenwulf, a kinsman of Offa. He was soon at war with Kent. In 825 the West Saxons defeated the Mercians at Ellendum. This was the end of the Age of Mercia and the stage was set for the great days of Wessex under Alfred.

Offa encouraged trade with the Franks and with other countries farther afield, and for this purpose he reformed the coinage in Britain. Up to now when people in Britain traded with neighboring states barter was the usual method employed, that is, exchanging goods for other goods. However, when trading abroad it was more convenient to use coinage of gold or silver, because whatever language they spoke foreign traders understood that gold and silver were precious metals and could estimate the value. So Offa struck some gold and silver coins, and one of his gold coins still exists; it carries the inscription 'Offa Rex' and is thought to have been made for the purpose of trading with the Arabs.