the origins of Parliament

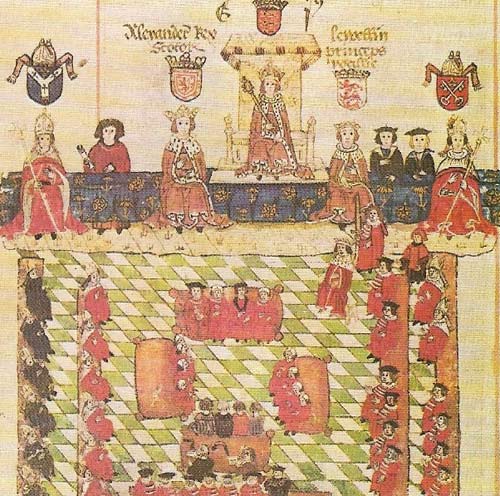

Figure 1. Edward I sits in Parliament with kings of Scotland and Wales in this contemporary illustration, but in fact they never attended together. Behind them are royal princes and the archbishops. Barons and the other bishops sit down both sides, and in the center are the judges, the councillors and the legal advisers of the Crown. The Commons and the proctors of the clergy (who must have outnumbered the rest) stand before the king.

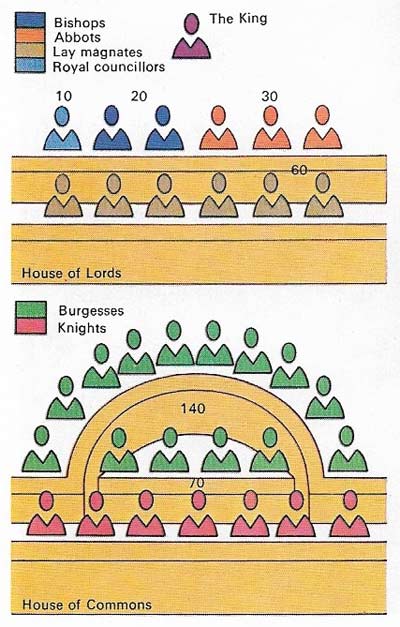

Figure 2. The structure of Parliament was fairly settled after 1350. After a peer had been summoned once, he was usually automatically called to later parliaments, and many knights and burgesses were chosen regularly. Some shires and boroughs did not bother to send representatives; as a result, the size of the Commons might vary. The royal councillors were a reminder of Parliament's original function.

Figure 3. Thomas Hungerford (d. 1398) was one of the first recorded speakers of the Commons. A client of John of Gaunt, one of the main objects of the Good Parliament's attacks in 1376, Hungerford represented the Commons the next year when Gaunt managed to reverse many of the Parliament's decisions. The speaker was elected by the Commons to be their spokesman, and also served as chairman of their debates. The institution of speaker crystallised the rising confidence of Commons: in the 1400s it felt able to oppose the king himself, asserting that Parliament was more competent in administrative matters than the king.

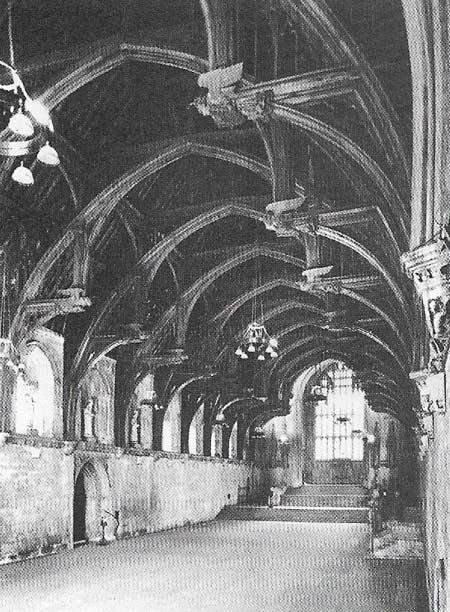

Figure 4. Westminster Hall, an 11th-century building, was reconstructed between 1394 and 1402. As the central hall of the king's palace, it was the usual place of formal sessions of Parliament in the Middle Ages. But sometimes, as in 1388, Parliament was held in the "White Hall".

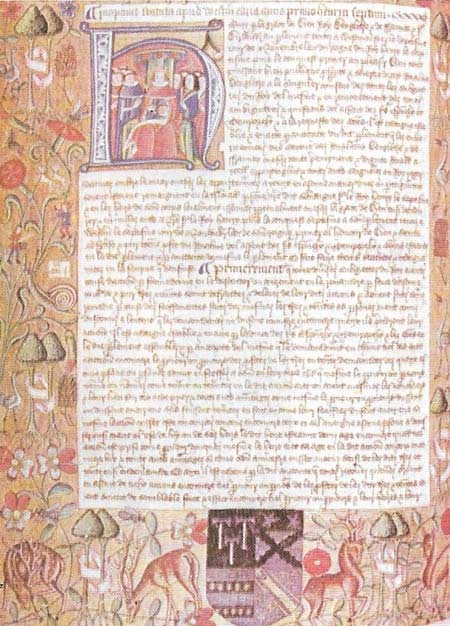

Figure 5. Henry VII formally declared his claim to the throne in Parliament in 1485, and recorded it in the Statute Roll, in the already antique "Norman-French" of legal documents. Unlike the long acts of Richard III and Edward IV declaring their titles upon intricate legal arguments, Henry's title rested simply on the declaration of Parliament in this quite short bill. It marks not only the succession of an entirely new dynasty, but also the recognition of the sovereign efficacy of Parliament. This foreshadowed the Parliamentary declaration of royal supremacy in 1534.

Figure 6. Henry VIII opened Parliament in 1485 and tried to ensure that it acted as an ally of the Crown. His policies were well suited to the interests of the merchants who were prominent in the Commons; he significantly reduced the power of the Hanseatic League in England and in 1496 passed the Magnus Intercursus to improve trading relations with The Netherlands. But when Henry had consolidated his income, he called Parliament only in cases of abnormal expenditure.

The English Parliament has no definite origin; but it clearly came into existence during the 13th century. At that time, the word "Parliament" meant a special session of the King's Council with the judges present to hear petitions to the king from his subjects. Early "parliaments" were largely occasions for judicial business in the presence of the king's councillors or barons, where great matters could be decided more solemnly than could be done by the judges alone. In the reign of Henry III (reigned 1216–1272), whose judges actively opposed baronial privileges, this was a widely popular precaution; and the greater the number of earls and barons, bishops and abbots present, the more definitive the settlement of the business. In this sense Parliament was a variation of the ancient king's Council.

|

| The three estates, the division of society into knights, priests and labourers, was basic to the concept of Parliament, but was not directly expressed in the structure of the Lords and Commons. |

Parliament and taxation

Parliament was not only judicial in function: it also provided an occasion for the king's subjects to give their consent to taxation and their advice on important matters. This function implied representation of the various interests and communities by men with power to bind their constituents to their decisions. Taxation with the consent of such representatives was the general rule in the "Parliaments" called by Simon de Montfort (c. 1208–1265) to show the broad support for his rebellion of 1258–1265.

|

| Simon de Montfort, whose shield is shown here, is sometimes said to have invented the English Parliament. To bolster his revolt against his brother-in-law Henry III he summoned a representative "parliament" in 1264. He genuinely believed in corporate, legal government, with frequent sessions of parliament to act as a bulwark against untrammelled royal or bureaucratic power. His ideas were later taken up by Edward I. |

Edward I (reigned 1272–1307) (Figure 1) defeated de Montfort's revolt in 1265, but during his reign all the various functions of Parliament came together: a session of the Council with as many councillors, barons and bishops present as possible; and representation of the shires by two knights, of the boroughs by two burgesses, and the clergy of the northern and southern provinces by proctors, all armed with plenipotentiary powers to grant taxes.

Advising the king

Although Edward I summoned representatives to only a few of his early parliaments, their presence became increasingly common as his need for funds grew, for without their consent taxes proved difficult to collect. By 1307, it was normal for individually summoned lords and representatives of the "Commons" to meet each year. Parliament was the creation of the government for its own purposes, but it was also a call to the propertied classes to participate in the processes of government. This call was accepted with reluctance by shires and boroughs that were preoccupied with local affairs. Nevertheless their representatives came, and in a fourteenth-century parliament the "Commons" were generally represented by men who had experience on the countless local commissions of the peace, for the collection and assessment of taxes and so on, that shouldered the executive work of government. For instance, a certain John Morteyn, who was a large landowner, several times serving in the wars of Edward II (reigned 1307–1327), a frequent member of commissions, and a strong partisan who evidently made enemies, acted nine times as Member of Parliament for Bedfordshire. Such men naturally had independent views, and their voice, joined with that of the lords, became increasingly influential.

|

| The Chapter House at Westminster was the venue when the Commons first sat separately from the Lords. This was during the "Good Parliament" of 1376 when impeachment was first used against royal ministers for allegedly embezzling taxes for the war. The step marked a clear realisation that the Commons has a different role from the Lords. By this time they had already evolved a formal procedure and elected a speaker. The Chapter House was used by the Commons until the mid-16th century. |

Parliaments continued to hear petitions and act as courts of justice, and to make grants of taxation to the Crown. But many parliaments did neither and it seems that it was their advice and on occasion their con-sent to legislation that was sought by Edward II and Edward III (reigned 1327–1377). By 1370 statutes had to be promulgated by the king in Parliament, and the kind of business on which they legislated broadened in scope: the Statute of Labourers, 1351, arose from petitions by landowners to Parliament to control laborers' wages.

The Lords and the Commons

During the period 1370–1450 Parliament evolved its classical structure and procedure. The representatives of the lower clergy broke away to form their own "Convocation", and by 1376 Lords and Commons met as separate bodies. Both Lords and Commons developed as political bodies able to put pressure on the king's ministers. Their weapon was "impeachment", a judicial process in which the Commons as a body "appealed" or accused a minister before the Lords who acted as judges of the case.

Under Richard II (reigned 1377–1399) and Henry IV (reigned 1399–1413), parliaments were keen to experiment with ways of influencing the processes of government: in 1377 they appointed special "war-treasurers" to supervise taxes granted for military purposes; in 1401 they proposed to grant no taxes before redress of grievances. In these demands, the Commons were led by a new kind of member: the national figure, often himself a member of the Council, independent, outspoken and politically experienced, such as Arnold Savage, Speaker in 1401 and 1404. In the hands of such national "front-bench" politicians Parliament was ready to assume a central role in the politics of the fifteenth century. Its elections became the arenas for factions to assert their authority, and many leading noblemen acquired sizeable groups of supporters in the Commons. Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509) used Parliament to legitimize his dubious claim to the throne (Figure 5), but tried to reduce its incursions on the royal authority by cutting his expenditure so that Parliament would not have to be called so often.