Age of Pericles

The age of Pericles.

The principal city-states of Greece in the time of Pericles. The Athenian empire is marked in yellow, the Peloponnesian League in red.

Socrates, the first great philosopher, in dialogue (philosophical discussion) with his friends.

What would it feel like to be an Athenian in the age of Pericles?

It must have been like an Englishman in the great days towards the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1, when England had survived the threat of the Spanish Armada; for in the same way Greece had survived the deadly menace of the Persian invasions. The Greeks had vanquished the greatest power of the times in the great battles of Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale, in which the Athenians had played an important and most honourable part.

The results of victory for the Athenians were an abounding confidence in themselves and in their free institutions, and a wonderful upsurge of creative spirit in all forms of art, literature, and thought. Most of the 50 years after the Persian Wars were dominated by the figure of the brilliant Athenian statesman Pericles. No wonder that the age of Pericles has been called the golden age of Greek civilisation.

From confederacy to empire

The Athens assumed the leadership of the Aegean Greeks after the battle of Mycale. The Confederacy of Delos was formed to defend its members against any further Persian attacks, and also to free the remaining Greek city-states on the coast of Asia Minor.

At first each member was independent in practice as well as in theory. Members provided either a contingent of ships or a contribution in money – tribute – to the allied treasury at Delos, according to Aristides's very fair assessment.

Most of the members, however, soon changed from providing ships to paying tribute; for them their citizens would not have to leave home, and the powerful Athenian fleet would protect them. Then, in about 468 BC, the island of Naxos tried to leave the Confederacy, although the fight against the Persians was not yet over. The Athenians and the allies forced Naxos to rejoin and to pay tribute. It was now clear that the Confederacy was intended to be permanent.

Athens had always been the dominant member, and very gradually Athenian influence grew greater and greater, until the former Confederacy of free allies had become an Athenian empire.

Led by Cimon (son of Miltiades, the victor of Marathon), the Athenian and allied forces did eventually clear the Persians from the Greek cities of Asia Minor. They also suppressed piracy in the Aegean. Meanwhile Pericles, who had become the leading statesman at Athens, tried to establish an Athenian land-empire on the mainland of Greece, even though this meant fighting Sparta at the same time as Persia. In this he failed; but the very attempt illustrates the Athenians' enormous self-confidence.

Wonders of the Acropolis

|

When peace was finally made with Persia (c.448 BC) and Sparta (445 BC), people asked what the Athenians were going to do with the tribute-money. (The allied treasury had been moved in 454 BC from Delos to Athens, and was under Athenian control.) They soon had their answer, 'The allies are paying us for their security,' said Pericles. 'So long as we give them that, we may do what we like with the money.' The Athenians agreed, and ostracised Pericles's opponent Thucydides (son of Melesias: not the same as Thucydides the historian). Whatever we may think of the morality of Pericles's view we cannot help applauding the use to which he put the tribute.

Pericles was determined to make Athens the most beautiful city in the world. The temples and other public buildings on the Acropolis had been burned when the Persians captured Athens in 480 BC. Now he was to rebuild them with as much splendour as possible.

To do this he enlisted the help of the greatest architects of the age – Ictinus and Callicrates, who designed the Parthenon, and Mnesicles, who designed the Propylaea (ceremonial gateway to the Acropolis). The Parthenom is a magnificent building, very large and yet beautifully proportioned. Rising from the steep rock which is the Acropolis, and gleaming with the slightly golden color of its Pentelic marble, it must have dominated Athens then, just as it still does today.

For decoration of the Parthenon, Pericles called upon Pheidias, one of the finest sculptors of this time. Thanks to Lord Elgin, much of the frieze he carved has been preserved, and can be seen in the British Museum.

Pheidias was also responsible for the gold and ivory cult-statue of Athens inside the Parthenon. He had previously made a colossal bronze statue of Athena ' the Defender', that stood outside on the Acropolis. Sailors many miles away in the Saronic Gulf could see Athens's helmet and spear-point flashing in the brilliant Mediterranean sunlight. (Unfortunately neither of these statues has survived.)

Periclean democracy

Perhaps the most remarkable achievement of the age of Pericles was the development of Athenian democracy. The reforms of Cleisthenes brought democracy to Athens. In practice, however, the aristocratic Council of the Areopagus continued to wield considerable influence, particularly because of its level-headed patriotism during the Persian Wars. In 461 the democratic leaders Ephialtes and Pericles passed a law depriving it of nearly all its powers: these were transferred to the Jury-Courts and to the Assembly. From now onwards the people were clearly to be sovereign.

Athens was now the most complete democracy the world has ever seen. All citizens were entitled to attend and vote in the Assembly, which passed all laws, and to serve in the Jury-Courts. All citizens in turn were also chosen by lot to serve on the Council of Five Hundred, which acted as a 'steering committee' for the assembly; but no one could be a member more than twice in his lifetime. Nearly all the magistrates were chosen annually by lot.

Consequently, all citizens had the chance to gain actual experience of government, and most of them did so. This was possible not only for the rich, who could afford to subsidise themselves, but even for the poorest citizens, since all state offices carried pay.

Only those posts for which specialist talent was essential were filled by selection. The most important of all the elected officers were the ten generals. it was by being elected general for year after year – and also by being a brilliant and persuasive speaker in the Assembly – that Pericles was able to maintain his position of leadership in the Athenian democracy.

From the age of Pericles onwards Athens was notable not only for her extremely democratic constitution but also for her remarkable personal freedom and tolerance. This was extended even to critics and enemies of the democracy, as well as to Metics (resident aliens), many of whom were happy to settle in Athens even though they did not enjoy the political rights of citizens.

It is important to remember that women had no political rights either. Nor did slaves – and there were a great many of them in Athens.

We should notice that, after the death of Pericles, Athenian democracy lasted throughout the Peloponnesian War – apart from two unpleasant and very brief intervals of oligarchy (rule by a few) – and throughout the difficulties of the 4th century BC, until the death of of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. Athenians democracy did not depend on the tribute from the empire, useful though that was in paying the daily fees of jurymen and magistrates.

The 'School of Greece'

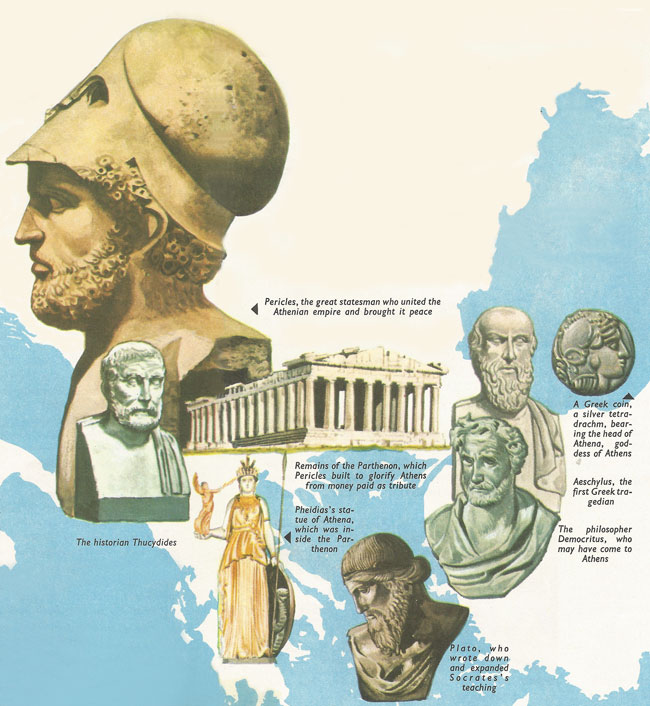

Pericles was proud to describe Athens as the 'School of Greece'. Not only were Athenian democracy and personal freedom an example to all; not only did her fine buildings make Athens the envy of Greece. Athens in the age of Pericles was a cultural center of great importance. Most of the leading artists, writers, and philosophers gravitated there – those, that is, who were not native Athenians themselves. Socrates, the greatest philosopher of the time, was an Athenian; so was his pupil Plato. The philosopher Democritus may have visited Athens. Thucydides, greatest of all ancient historians, was an Athenian. So were the three great tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and the comic poet Aristophanes. It was for the Athenian dramatic festivals, in fact, that all their plays were written.

After Pericles

Athens lost her empire and her political leadership in the Peloponnesian War.

Culturally, however, Athens continued to dominate Greece for the rest of her independent existence. In particular, the Attic (that is, Athenian) dialect of Greek became the standard literary form of the language. it was the Attic dialect that was spread all over the eastern Mediterranean and beyond by the conquests of Alexander the Great. It remained the 'common language' (koine dialektike) of those areas even under the Romans; and it is from the koine that the modern Greek language has developed.

For us in the twenty-first century, however, perhaps it is the idea and practice of democracy and personal freedom that is our greatest heritage from the age of Pericles.