Pompeii

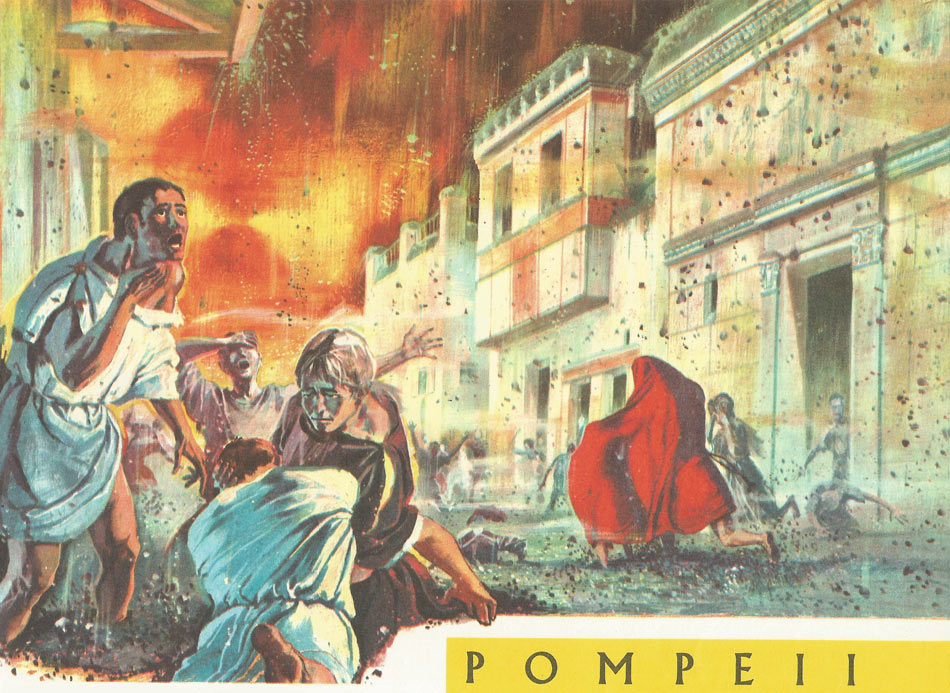

The destruction of Pompeii.

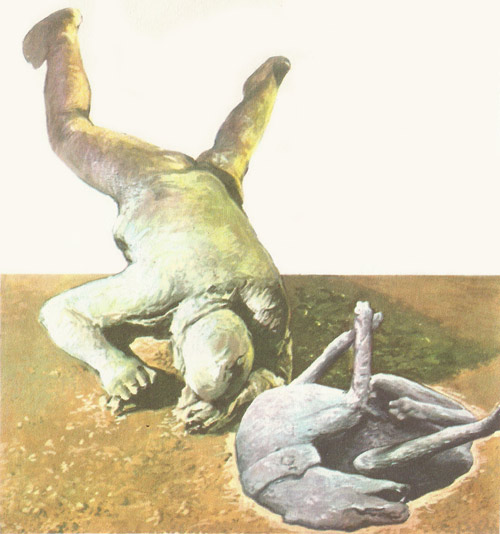

This is a cast of one of the people found at Pompeii: a young woman has fallen on to her face, and has died while supporting her head on her arm. To her right is the cast of a chained watchdog, caught by death while straining with all his might to break the chain by which he had been tied.

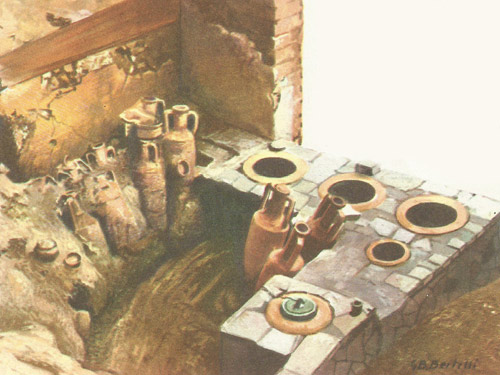

This is the inside of a thermopolium, or 'bar', where hot and cold drinks were sold. The room was full of amphoras (jars) for wine; the holes in the bench served to keep the amphoras upright. On the pavement outside, coins were found which had been put down in payment by the last customers and thrown about in confusion.

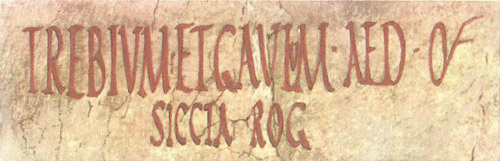

The outside walls of both private and public buildings in Pompeii bear a surprising variety of writing, Much of this consists of advertisements, carefully inscribed by professional signwriters in capitals in red or black paint. This illustration shows an election 'poster', and reads: TREBIUM ET GAVIUM AED(iles) OVF (abbreviation for "oro vos faciatis"). SICCIA ROG(at)'. This means: 'Election of aediles (local magistrates). Vote for Trebius and Gavius, Siccia's candidates'.

A dining room (triclinium) in a house at Pompeii. Even the pottery on the table is original. In many houses in Pompeii the domestic utensils were found exactly as they had been abandoned by the occupants in their flight. To the right is an oven which has a grate and pots still in their original places. Below is a loaf of bread, charred but still easily recognizable.

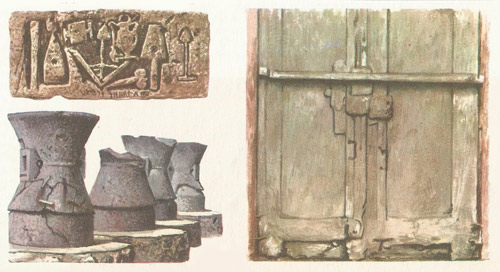

Upper left: A blacksmith's sign, carved in stone. It shows some of the objects produced in the shop: shovels, shears, and squares. In many shops forceps, scales, hinges, locks, and tools have been found. Lower left: These are grain mills found in the back room of a baker's shop. The upper millstone was turned either by hand or, more often, by donkeys, and the grain when ground into flour was collected in the circular base. Right: This is a door of a house, solidly barred from the inside.

South of the great city of Naples, in part of the territory called Campania, stands a sinister mountain with a double peak. In ancient times it seemed peaceful enough, covered with woods and vineyards. But it is not an ordinary mountain: it is a volcano. Its name is Vesuvius.

Pompeii and Herculaneum

Vesuvius had slept for so long that the Oscan peoples who lived in Campania were not afraid of it. Some time before the 6th century BC they built a city which they called Pompeii, near the coast and right at the foot of the mountain. Eventually this city came under the control of the Romans, who in 80 BC installed a colony of veteran soldiers there.

From then onwards Pompeii became more and more Roman in every way: in decoration, in architecture, in language (Latin replaced Oscan), in weights and measures. By the 1st century AD it was a pleasant and prosperous pleasure-city where wealthy Romans went to spend the summer, as they did also to its neighbor, Herculaneum, on the other side of Vesuvius. Its people generally lived in spacious houses: these were not at all like the cramped blocks of flats (insulae) in which ordinary people had to live in Rome, and which can still be seen in the ruins of ancient Ostia.

The giant awakes

On 24 August, AD 79, Vesuvius unexpectedly awoke. The eruption seems to have taken most people by surprise, despite an earthquake some 16 years earlier which had caused considerable damage. The Younger Pliny happened to be nearby at the time, and wrote an eye-witness account of the eruption in two letters to his friend Tacitus, the historian.

The first sign of trouble was the appearance of an unusually large cloud above Vesuvius. It rose to a considerable height before spreading out at the top, not unlike the characteristic 'mushroom' shape of a modern nuclear explosion: Pliny compared it to a very tall pine-tree with spreading branches. In color it was 'sometimes white, sometimes dirty and mottled, depending on whether it had carried up earth or ash'.

That monstrous cloud spread out so far that it covered the city of Pompeii. People were standing in the streets, watching it in fear, when they heard around them a sound like the beginning of a hailstorm. Hot ashes and little bits of pumice-stone were raining down upon them. Everyone covered their heads: some fled at once to the sea and escaped; others ran into their houses, waiting and hoping that the strange phenomenon would end soon.

Death of a city

But the hail of lava and ash continued, and the courtyards and streets began to be choked with it. A roof started to collapse here and there under the increasing weight. Added to this there were several earthquake shocks, and 'from Vesuvius very broad flames and lofty fires were blazing in several places'.

Those still in Pompeii now realized how serious their danger was. Many opened the doors of their houses with a struggle and fled through the streets. Pliny tells us how his relatives 'put pillows on their heads and fastened them with linen, as a protection against the "hail"'.

It was too late. Most of those who fled met their death upon the roads outside Pompeii: those who remained in the city, sheltering in the cellars, likewise perished from the poisonous vapors from the volcano. Some must have been buried alive; for the fall of lava and ash continued without interruption for three days.

When Vesuvius at last became calm again at dawn on 27 August, and the summer sun returned in its brilliance to the beautiful Bay of Naples, Pompeii (and Herculaneum) lay buried under some 20 feet of volcanic dust.

Modern excavations

The cities were not rebuilt, and in the Middle Ages even the site of Pompeii was forgotten.

At last it was rediscovered, and the first excavations took place in 1748. Pompeii proved a much easier site to excavate than Herculaneum, so naturally archaeologists have concentrated on it. Rather more than half the city has now been uncovered. Since 1951 the work has been partly financed by a local land reclamation scheme: the rich volcanic soil from the excavations goes to improve neighboring agricultural land.

Pompeii is particularly interesting because it is one of the very few cities in the world that has passed from life to death and total burial within a few hours. The modern visitor can see a 1st-century city that is complete and almost intact.

In the earlier excavations any discovery of special interest was normally taken away, either to the museum on the site at Pompeii or to the National Museum at Naples, which is, therefore, one of the few places in the world to have an art gallery of pictures painted by the ancient Greeks and Romans. Then the 'House of the Vettii' was discovered. This is a Roman house in an almost perfect state of preservation. The excavators have now decided, wherever possible, to keep discoveries in their original places, protecting them where necessary.

One of the most moving aspects of a visit to the excavations at Pompeii are the clay 'casts' which reproduce exactly the forms of people who died in the disaster. The ash covered their bodies: in the course of time, the organic matter decomposed, leaving an impression in the ashes. By pouring clay into these cavities, the cast of the buried person can be obtained.

Up to the present, 14 casts of human bodies have been obtained and over 3,000 skeletons have been discovered.