preclassic America to AD 300

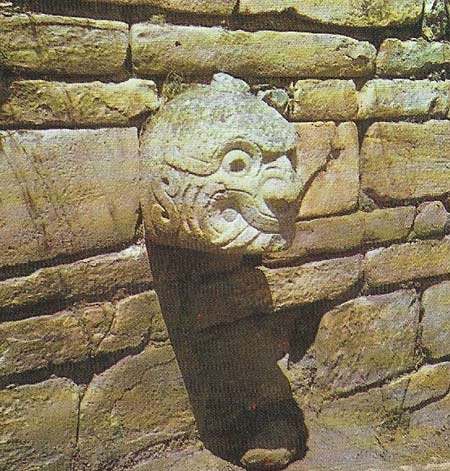

Figure 1. Human and feline characteristics are combined in a sculpture of a monstrous head projecting from the wall of the Castillo, the main structure at Chavin de Huantar. The undressed but neat masonry contrasts with the sophistication of the carvings. The site lies in a high valley in the upper Amazon basin.

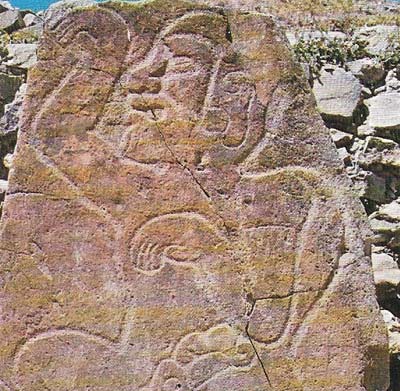

Figure 2. Figures of danzanies – dancers – at the Zapotec center of Monte Alban, Oaxaca, Mexico, date from about 500 BC and resemble Olmec art of the same period and earlier. The abandoned poses, closed eyes and various details on the bodies suggest that the figures depict slain warriors.

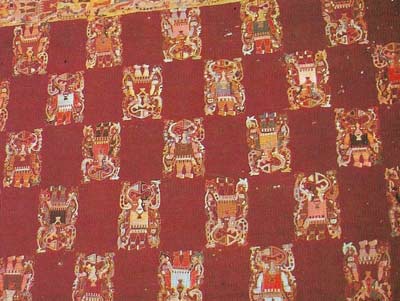

Figure 3. Part of a richly decorated textile from the desert cemeteries of the Paracas peninsula, on the coast of south-central Peru, shows a complex design that is repeated similarly on each of the many panels. These textiles have been preserved by the dry climate of the Peruvian coast, and provide an idea of what may have been lost elsewhere.

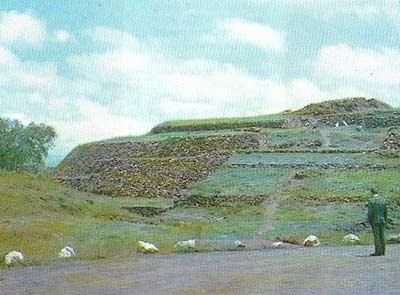

Figure 4. The circular and stepped pyramid at Cuicuilco in the Valley of Mexico on the edge of present Mexico City was the main structure of a city that flourished at about the time of Christ. It was overwhelmed by an eruption of the volcano Xitle and buried under lava, but has recently been excavated and restored.

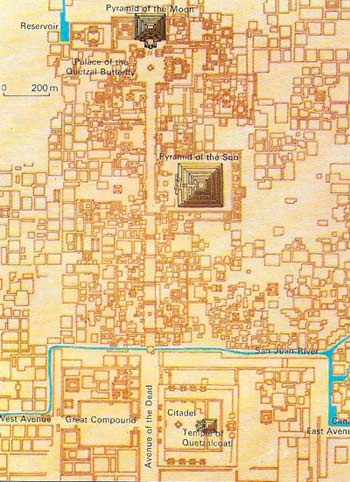

Figure 5. Teotihuacan, a great city in the northeastern basin of Mexico, began its dramatic rise about 100 BC and from AD 100–700 had a population approaching 200,000. The long Avenue of the Dead runs south from the Pyramid of the Moon to the citadel and market compound in the center of the city.

Figure 6. Reconstruction of Pyramid E-VII-Sub shows a Pre-classic temple of about AD 200–300 at the Maya site of Uaxactun, Guatemala, which archeologists found preserved beneath a later structure.

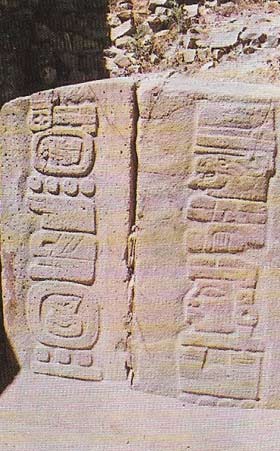

Figure 7. Mayan writing has more than 800 hieroglyphs, few of which have been translated although the Mayan calendar is understood. This is part of an inscription on one of the stelae at Quirigua, Guatamala.

The period between 2200 BC and AD 300 saw the rise of the first civilizations in both Mexico, where it is known as the Formative or Preclassic, and Peru. By 1500 BC agricultural villages in both Mesoamerica and South America were developing with craft specialization in such fields as ceramics; society was also moving towards stratification, expressed in the first public architecture. The first truly complex society, the Olmec culture, based in the tropical lowlands of the Mexican Gulf coast, had appeared by 1200 BC. The first great ceremonial center was San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, where the whole form of a natural ridge was altered by the construction of ridges and platforms.

Spread of Olmec culture

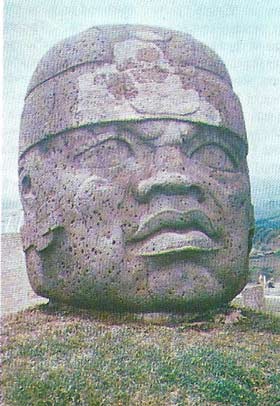

During excavations numerous pieces of monumental sculpture in volcanic stone were found, including giant heads deliberately defaced and buried. The stone itself came from the Tuxtla Mountains many kilometers away and the presence as well as the sophistication of the sculptures indicates an organized labor force, a body of specialist sculptors and a powerful government whose patronage extended from sculptors to lapidaries and potters as well. A further range of sculpture and a large conical pyramid were found at another Olmec center, La Venta.

|

| This giant head of the Olmec period, found at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan near the Gulf Coast of Mexico, dates from about 1200–900 BC. Several such heads were found at the site, and others are known from La Venta and a number of smaller sites including the early Laguna de los Cerros. They are thought to depict the Olmec rulers and are made of volcanic rock brought at least 100 kilometers (60 miles) from the Tuxtla Mountains, giving strong evidence of the social control exerted. The Olmec culture is the first complex society in Mesoamerica to attain a level that can be described as "civilization" and it stimulated later developments. |

Olmec trade spread far into the highlands of Mexico, Oaxaca being a source for various minerals, and the valley of the Rio Balsas beyond Mexico City perhaps being the origin of the blue jade favored by the Olmec; another possible source is even more distant, in Costa Rica. Rock carvings and cave paintings in Olmec style are known from western Mexico, and the carvings continue eastwards into El Salvador. Whether diffusion of this artistic stimulus was commercial, religious, diplomatic or military, it has a good claim to being the first pan-Mesoamerican style. There is some evidence that the Olmec possessed a system of numerical and perhaps other notation, but whether this can be described as "writing" in its true sense is still a matter for argument.

In Peru from about 1000 BC onwards a similar diffusion of the Chavin style occurred. The style involves both birds of prey and feline-human compounds (Figure 1) with serpent attributes, and is full of arcane allusion. The style is named after the site of Chavin de Huantar, about 3,000 meters (9,750 feet) up and just below and east of the crest of the Andes in central Peru, where a complex of massive stone buildings with subterranean galleries stand round formal courtyards. Some of the galleries contain sculptures, such as the Lanz6n that stands in the deepest part of the main structure and portrays a mythical being.

Chavin influence on arts and crafts

The Chavin style is also found in pottery, and examples of it are known from as far north as Ecuador, while in textiles Chavin influence is found in the Paracas region (Figure 3) in southern Peru. Chavin influence continued until about 200 BC, and may have just continued in a provincial form in the sculptures of San Agustin in southern Colombia. The sites at San Agustin cover a wide area on the hills around the modern town and consist of megalithic chambered monuments and feline, fanged sculptures. They are dated from AD 1–500, although more radiocarbon dates might vary this.

Elaborate gold work of the Chavin period is found in the Lambayeque valley and other regions of northern Peru. It initiated a tradition of working precious metals that continued until the Spanish conquest. In the Viru valley, south of Trujillo on the Peruvian coast, major centralized settlements developed during the early centuries AD, apparently in response to population pressure and competition for resources. Pucara in southern Peru was an important cultural center, quite unrelated to Chavin.

From about 500 BC the rise of Zapotec culture (Figure 2) in the Valley of Oaxaca in southern Mexico accelerated. The first monumental inscriptions in hieroglyphic script from the New World are found at the great hilltop center of Monte Alban, together with large stone buildings and low-relief carvings of humans. Another structure, Mound J, could well have been an astronomical observatory. By the end of the Preclassic period Monte Alban already possessed the spacious formal layout, the huge open plazas and the massive platforms that mark its further development in the Classic.

|

| Two sculptured stone slabs or stelae at Monte Alban bear short inscriptions in a form of hieroglyphic writing, including long bars and round discs that probably denote numbers, a bar equaling 5 and a disk 1. These stelae, dating from about 500 BC, are the earliest dated writing in the ancient Americas. |

The Valley of Mexico, after a period of Olmec influence, saw the rise of a number of independent political units round the margins of its broad, shallow lakes. Among these was Cuicuilco, which was destroyed about the time of Christ by an eruption (Figure 4). Teotihuacan, a rival state in the northeast of the valley, grew in the next century into a centralized, planned urban settlement (Figure 5) which by AD 150 covered more than 20 square kilometers (7.7 square miles), with a growing population.

Teotihuacan trade extended a long way eastwards into the Maya area by about AD 400.

The beginning of the Maya culture

The Maya are the reason for the Classic period formally beginning at AD 300, because that is roughly when they started to erect monuments bearing inscriptions (Figure 7) in the Long Count, a complex calendar that enables Maya monuments (Figure 6) to be dated to within a-day. It now seems that Maya culture itself acquired most of the attributes of civilization during the late Preclassic period.