Realist painting in the 19th century

Figure 1. David Wilkie’s “Chelsea Pensioners reading the Gazette announcing the Victory of Waterloo” (1822, detail), is an example of early “popular” Realism.

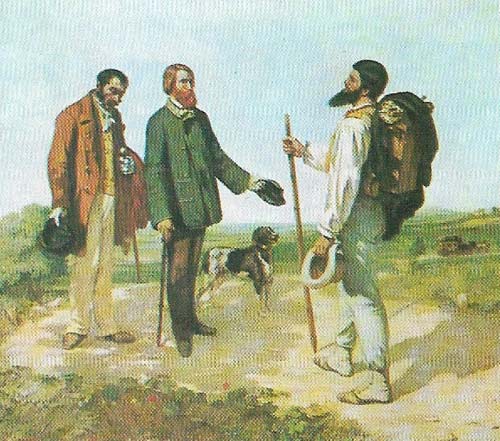

Figure 2. Gustave Courbet's "The Meeting" (1854), familiarly known as "Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet!", shows the artist being greeted on the road by his friend and patron, Alfred Bruyas.

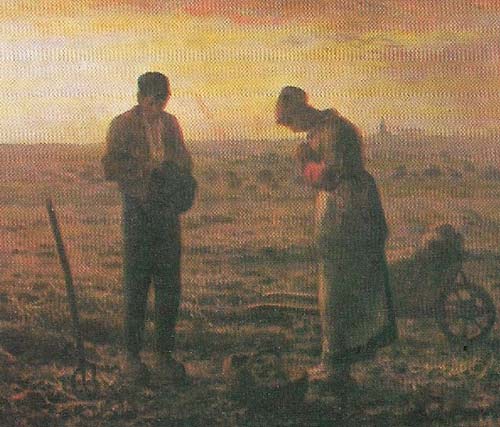

Figure 3. The labors of the fields, previously depicted in pastoral scenes, were treated realistically by Jean Francois Millet. In "The Angelus" (c. 1858) he added an element of religious sentimentality which made the picture especially popular at that time.

Figure 4. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848, sought to combine fidelity to nature with the purity of spirit of the Italian painters before Raphael. These qualities are reflected in John Everett Millais' "Sir Isumbras at the Ford" (1857).

Figure 5. "Derby Day" (1856–1858, detail), by William Powell Frith (1819–1909) follows Hogarth and David Wilkie rather than either the Pre-Raphaelites or the French Realists. Yet it shows a characteristic side of 19th century life – its energy and vulgarity – and has the contemporary feel of a magazine illustration. The picture also contains some witty character drawing and is composed with considerable skill.

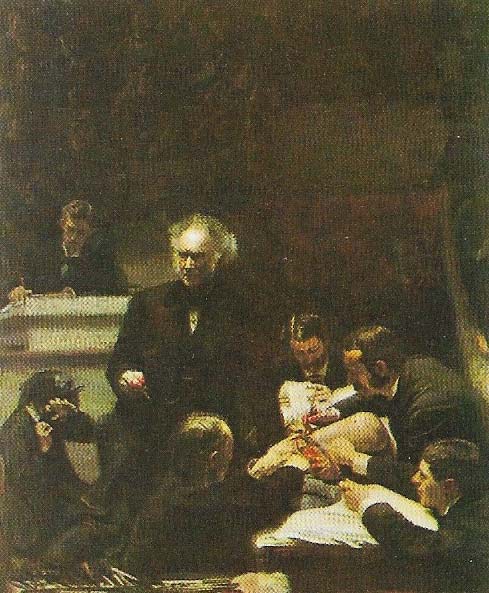

Figure 6. The discovery of anesthetics and antiseptics made surgical operations (as distinct from dissections) a possible subject for art. The opportunity was seized by the American Thomas Eakins in "The Clinic of Dr Samuel Gross" (1875).

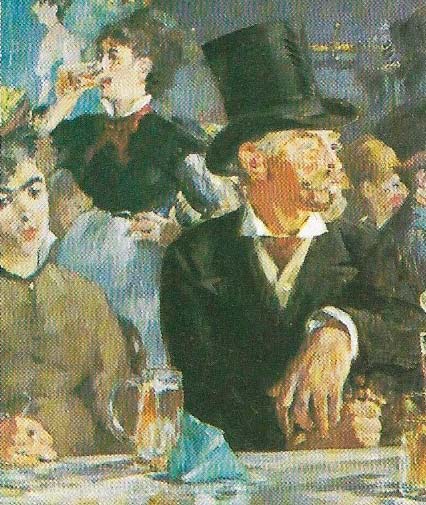

Figure 7. After 1860, cafes were a popular subject of the Realists, and cropping of the image to produce a casual effect, as in a photograph, became common. "Au Café" (1878) by Edouard Manet (1832–1883) is an example of this. It also shows the reintroduction of vivacity and color as the painter's technique moves towards Impressionism.

Figure 8. "A Visit to Aesculapius" (1880), by Edward Poynter, shows what the grand style of history painting came to in the end. For all the correctness of the drawing, the intrusion of realism and the trivial subject – a parade of naked Victorian ladies with imaginary illnesses before a classical faith healer – make the picture embarrassing.

Realism is the term used to describe the most characteristic style that arose in painting, particularly in France, between the end of Neoclassicism and Romanticism and the beginnings of Impressionism. It belongs essentially to the years 1840 to 1870, although some paintings with realist tendencies were produced before this date, and the style continued to flourish until almost the end of the century. A significant event was the development, during the same period, of the new art of photography..

|

| The symbol of 19th century Realism in art is, ironically, not a painting but a photograph. Photography, which began to become effective in the 1840s, fulfilled the Realist painter's wildest dreams, yet did so in a medium that was not his own and that dispensed with the arduous process of matching nature by means of brushmarks. In fact the two arts coexisted in an uneasy but mutually beneficial relationship for the rest of the century. The inventor of the first practical and successful photographic process was a Frenchman, Louis Daguerre (1789–1851), portrayed here in a "daguerreotype" by the English photographer, J. J. E. Mayall, in 1848. |

The social context

Photography as the ultimate in pictorial realism was at once a challenge to painting and an echo of, and influence on, it. At first it was chiefly painting that influenced photography (many of the early photographers began their careers as painters) but from about 1860 onwards the influence began to flow the other way (Figure 7).

Realism grew as much from social as aesthetic motives, but the reasons for it were not the same in all countries. In Britain, where it begin first soon after 1800, it succeeded chiefly because, in the nineteenth century, art for the first time became really popular with a mass public. The more traditional styles of painting, which depended for their appreciation on an educated few, fell out of favor. They were replaced by a new, more direct art (Figure 5) representing (within tasteful limits) things as they were, in a style based on the accepted models of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish painting and with a strong element of humorous or sentimental narrative which enabled pictures to be "read" like a novel.

The pioneer of popular narrative painting was David Wilkie (1785–1841), who was actually patronized by the aristocracy but whose art reached a wide public through exhibitions and prints. Wilkie was the most popular artist in Britain during the first 40 years of the century, and his approach (Figure 1) became the model, more or less, for all subsequent British Victorian artists.

The situation in France was different and Realism began there later. It was not a popular style as it was in Britain; rather, it was serious and committed, even subversive. Whereas in Britain Realism developed within the Academy, the home of official and aristocratic taste, in France it was conceived partly as an attack on the official historical art sponsored by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, then the guardian of academic values.

Influence of Courbet

The leading French Realist was Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), whose career ran from the mid-1840s to the early 1870s. He was aggressively bohemian and provincial, a democrat if not a revolutionary, and he founded the doctrine, later a Realist battle-cry, that the artist must be "of his own time". "Painting is an essentially concrete art", he wrote, "and can consist only in representation of real and existing things."

In contrast to British painters, Courbet played down the element of narrative and, for virtually the first time, represented ordinary provincial and working-class people in everyday terms. This was thought undignified. A picture such as "The Meeting" (Figure 2), which shows the rich bourgeois patron doffing his hat to the journeyman artist (Courbet himself), caused offence not only because of its reversal of the normal relationship between artist and patron but also on account of its apparent lack of any interesting subject.

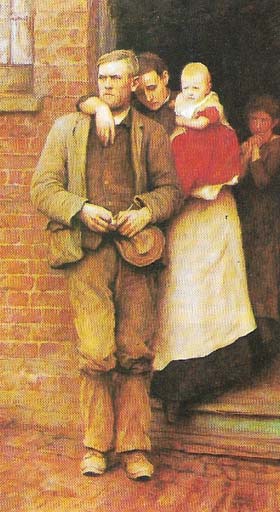

With Courbet, French Realism began to take on a class-conscious, political tendency and to be identified with grim and sordid subject-matter. It is also noticeable that Realist paintings from this time onwards are normally dark in tone and drab in color, resembling contemporary photographs. Although Courbet himself does not seem to have intended his work as social propaganda, the way towards this was now open and many painters took it. For instance Jean Francois Millet (1814–1875) showed the hard life of a depressed peasantry redeemed only by the consolation of religion (Figure 3) and later, in England Hubert von Herkomer specialized in painting the industrial working class.

|

| "On Strike" (1891), by Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914), enters, with vivid realism, the world of the industrial working class. Its style reveals the direct influence of photography, although this is most evident in black-and-white reproduction. As with most life-size Victorian paintings, the original disappoints owing to its labored execution. |

The 19th century was the first in history to take work seriously as a subject for art and to treat it not in some symbolic guise, as had been done by artists in the pastoral tradition, but as a dedicated, often grinding and monotonous activity. Another interesting development was the realistic portrayal by the American Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) of the working lives and achievements of surgeons and inventors (Figure 6).

Morality, mythology, and history

While Realism was usually identified in this period with modern life and dealt with questions of social rather than individual morality, there were exceptions to both these rules, especially in British painting. Pre-Raphaelitism was an English style of the late 1840s and 1850s that applied realistic pictorial aims to personal moral problems and to religious themes (Figure 4). In both cases it produced a sense of shock comparable to Courbet's paintings and for fundamentally the same reason: that art was being used to disturb its audience and not to please it.

|

| William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) was a Pre-Raphaelite who in "The Awakening Conscience" (1853) turned his attention to personal morality, preaching a sermon to his middle-class audience on the evils and pathos of adultery. The girl starts up from her lover's lap on being reminded of her lost innocence by the tune he is playing and by the sunlit garden outside. |

Finally, Realism increasingly invaded the realm of historical and mythological painting, reducing that once noble and intellectual genre to the level of a make-believe voyage into past time, as in the languid reconstructions by Edward Poynter (1836–1919) and others of the daily lives of the ancient Greeks and Romans (Figure 8).