Roman art

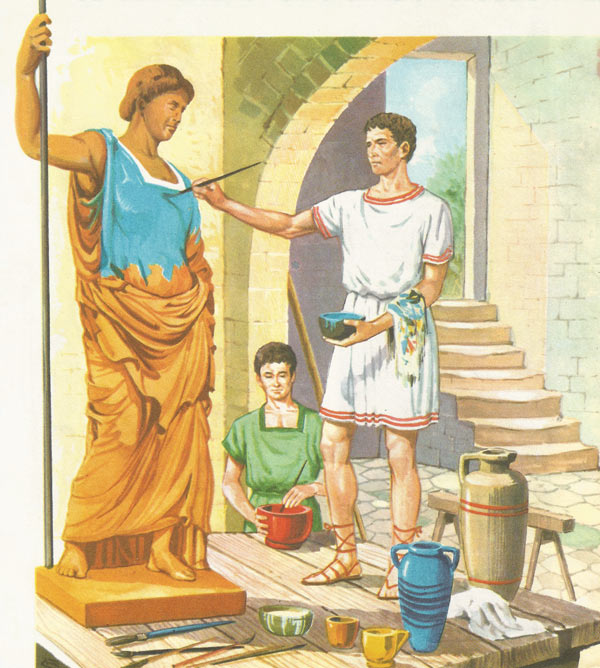

The workshop of a Roman sculptor in the early days of the Republic. The artist is engaged in painting a terracotta statue.

Statue of the Emperor Augustus (about 20 BC).

Detail of the Capitoline wolf, a bronze work by Etruscan artists of the school of the sculptor Vulca, who worked in Rome in the 6th century BC.

The 'Primavera', a fresco of the 1st century AD, found at Stabia. One of the masterpieces of Roman paintings. The figure is called 'Primavera' (Spring), because of its close resemblance to a famous painting of that name by Botticelli, the Renaissance painter.

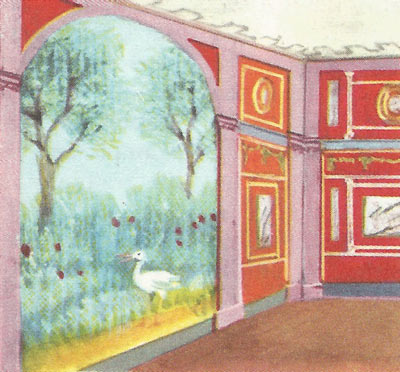

From the house of Livia, the mother of the Emperor Tiberius, in Rome. It gives the impression of looking out in to a spacious garden. Wealthy Romans decorated the walls of their houses with wall paintings featuring architectural details and landscapes.

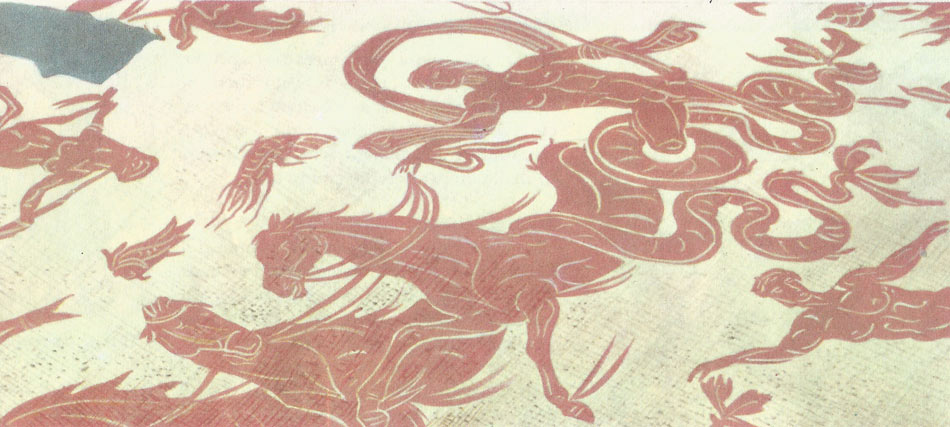

A magnificent mosaic decorating the entrance to a bathing establishment.

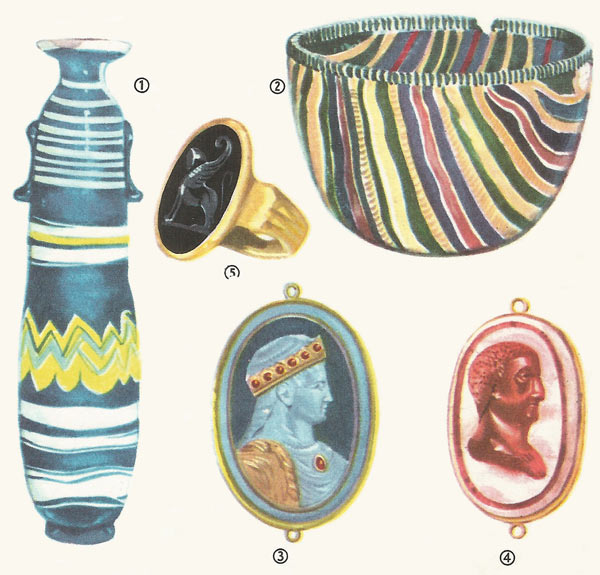

1 and 2: Colored glass vase and bowl. The art of glass-making reached Rome from Sidon and Alexandria during the reign of the Emperor Tiberius, and quickly began to flourish. Glass windowpanes were not used until much later; thin slices of horn were used at the time to let in a little light.

3 and 4: Two cameos in hard stone. These are produced by cutting stones which are composed of layers of different colors. The art is still practiced in Italy today.

5: An object of exceptional historical interest: the signet ring of the Emperor Augustus. This ring of gold and jasper was found in the tomb of the emperor. We are told that Augustus adopted the sphinx as his personal symbol because it represented the silence and discretion he displayed in the administration of the Empire. The same symbol is seen on the shoulders of his armour on his statue. It also appeared on a number of Augustus' coins. Finds of such a personal nature are rare in the excavations of archeologists, and it is hard to remain unmoved at the sight of a ring that was for many years on the finger of the founder of the Roman Empire.

The early Romans were famous for their austerity. It is said that during the second Punic War (218–201 BC) there was only one set of silver tableware in the whole of Rome. When they wished to impress some distinguished foreign guest, the leading families of Rome used to pass this unique set from one to the other. At the same period the Romans made little effort to decorate their buildings. It is certainly true that their temples were decorated with crude reliefs and patterns in terracotta, and contained clay statures made by Etruscan artists who had settled in Rome. To Greek visitors, however, who remembered their own cities richly decorated with statues of every material, and with magnificent temples, such feeble efforts seemed ridiculous. But the Romans at this time cared little for the opinions of the Greeks, whom they regarded as weak and unwarlike, and concentrated all their efforts on making Rome great and strong. They spent their money on building bridges, walls, and aqueducts, and on building up a powerful army and navy. They paid little attention to art; and when they did, it was for the purely practical purpose of honoring the gods. When Camillus captured Veii, the leading town of the Etruscans (Rome's most powerful enemy), in 396 BC, he removed all the statues of the gods from the captured city and took them to Rome. He did not do this in order to make Rome more beautiful, as we might suppose, but simply in order that Rome might feel that she now had these powerful divinities under her control.

Greek influence on Roman art

As Rome began to grow and have more contact with Greece, the Roman attitude began to change. A Roman poet said that Greece after her conquest had conquered her vanquishers; he meant that Greek ideas had had a great influence on the Romans, and this was particularly true in the field of art. This process began during the second Punic War. In 212 BC Claudius Marcellus conquered Syracuse, one of the leading Greek colonies of Sicily, and sent back to Rome a large number of fine statues and other works of art.

The enthusiasm and interest which they aroused on their arrival in Rome was so great that three years later, when Fabius Maximus conquered Tarentum, he behaved very differently from Camillus, and allowed the Tarenines to keep statues of their gods, which were of little artistic value, while he removed to Rome a great many Greek masterpieces, including a splendid bronze statue by the famous Greek sculptor Lisippus. In the Senate, Cato, the strenuous defender of the customs of ancient Rome, launched bitter attack on these 'decorations', which were ruining the austere character of the city. Nobody paid any attention to him. Soldiers were returning from the war on the Greek mainland, and were full of all the wonders they had seen in the famous cities of Greece – Athens, Olympia, and Corinth: marble buildings decorated with statues, bronzes, painted vases, engraved silver cups. A passion for beautiful things seized the Romans.

Sculpture

Roman sculpture consisted largely of copies of Greek originals; a good sculptor was not expected to make new statues, but good copies of Greek ones. To this we owe a great deal of our knowledge of Greek sculpture, since so many of the Greek originals have disappeared. Even when they wanted to make a statue of a living person, the Romans got their ideas from a Greek statue. The statue of Augustus is, for example, in the position of the arms and legs, and exact copy of a famous statue by a Greek sculptor, Polyclitus.

The Romans only showed originality in two forms of art: sculptured reliefs and portrait busts. The reliefs round the famous column of Trajan in the Forum give a vivid picture of Trajan's campaign against the Dacians, and all the scenes are well executed. In these reliefs, as in those on the arch of Titus, the geometrical character of Etruscan art combines with Greek harmony and Roman realism to produce powerful and dramatic masterpieces.

The Romans' interest in accurate portrait busts had a practical origin. The leading Roman families used to keep portraits of their famous ancestors, which had been modelled in wax on the face of the dead man. These masks were then carried at the funerals of their descendants. Many of the portraits that have been discovered at Pompeii are extremely lifelike.

Painting

Our knowledge of Roman painting comes almost entirely from paintings that have been found on the walls of some Etruscan tombs at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Generally, the Romans did not paint on canvas or wood, but on the walls of their houses. As Roman houses had no outer windows, the painters tried to make their paintings look like a view through a window into the surrounding countryside.

The most beautiful city in the world

When Roman soldiers began to conquer Greece and the rich province of Asia, enormous quantities of artistic objects flowed back to Rome as the result of the plunder.

Every general who returned victorious to Rome celebrated his triumph by having an enormous number of statues in his procession. Fulvius Nubilior had 230 marble statues and 285 bronze ones in the triumph which he celebrated in 187 BC.

His example was followed by Aemilius Paulus and Caecilius Metellus, the conquerors of Macedonia, by Publius Scipio, the conqueror of Carthage, and by Sulla and Pompey after their victories in Greece and Asia Minor. Even Delphi, the center of Greek religion, was not spared, and other ancient and honoured shrines were plundered and the masterpieces that they had treasured were all taken to Rome.

From the time of Augustus onwards Rome was the most splendidly built and decorated city in the ancient world. Augustus himself claimed to have transformed Rome from a city of brick into a city of marble, and all his successors beautified the city with new buildings or works of art.

In addition to works of art, craftsmen of all kinds – sculptors, painters, and engravers – poured into Rome. They were mostly Greeks, for Roman art was largely inspired by Greek art and there was little in it that was entirely original. Here, almost more than anywhere else, Greece had conquered her conqueror.

But while Greek art tried to show the artist's ideal of the beautiful, the Romans concentrated on glorifying the history and greatness of Rome. The reliefs on Roman arches and columns tell the story of Rome's triumphs, her conquests, the spread of civilization by her armies, and the glorious deeds of her generals and emperors. In Roman art we see the deeds of living people, not the mythological actions of legendary gods and heroes, which were the usual themes of Greek art. This explains why the only sort of art in which the Romans achieved any original work was portraiture; some of the Roman portraits are the most realistic masterpieces in the world.