Roman roads

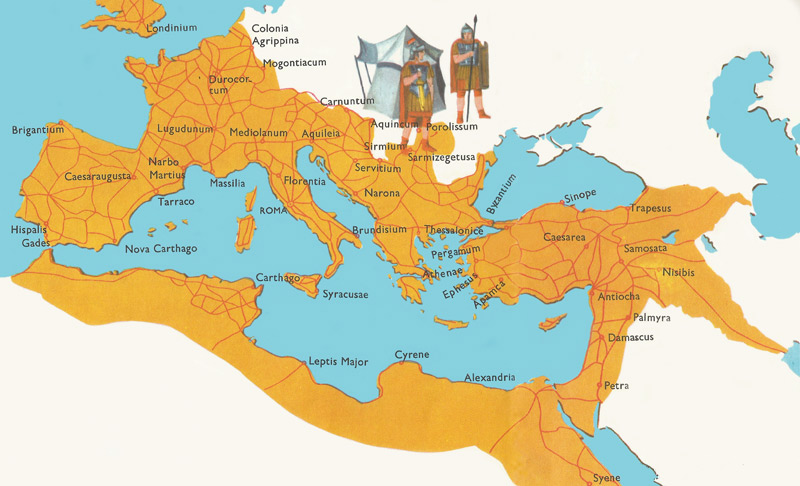

Figure 1. The main Roman roads at the tie of the greatest expansion of the Roman Empire.

Figure 2. The main Roman roads in Britain.

Figure 3. An early stretch of the Via Appia, along which some of the noblest families of Rome had their burial places.

When the Emperor Augustus had completed the conquest of Spain he celebrated the fact by issuing coins bearing the words 'ob vias munitas' (on account of the roads being built). This is only one fact that helps to show how much importance the Romans attached to the building of roads in the countries they had conquered. Originally, of course, the roads were intended for the rapid movement of troops across the country, but these great road systems helped to encourage trade and communications with other nations. The comparative ease of travelling in Roman colonies helped the rapid spread of Christianity; we know from the bible how easily St. Paul travelled in Asia Minor, for example. The speed with which the Romans could travel along their roads is shown by the fact that when Julius Caesar had to return to Gaul from Rome, after a rebellion had broken out there, he covered the 750 miles between Rome and his legions in only eight days.

A network of roads

Roman roads are naturally most common in Italy itself. As the Romans conquered other Italian cities they laid down a number of roads, all starting from a golden milestone in the heart of Rome. The map shows the network of modern one showing the railways of Europe, you will see how, in many cases, the railways follow the line of the roads. The Roman engineers had a very good eye for country, and their experience told them where to build the roads. In many parts of Europe stretches of the old Roman roads are still seen. They are always carefully made. The usual procedure was to lay a foundation of flagstones covered by a layer of rubble with a bed of concrete above it, in which the paving stones were set. Roman Britain was no exception to this rule. Over 5,000 miles of Roman roads have been traced in Britain and there must have been many more which have since disappeared. The network of main roads was built very early on during the Roman occupation, and they were used for the rapid movement of troops. As soon as the Roman forces, advancing from the southeast, had reached a line stretching from Seaton in Devon to Lincoln, they built the Fosse Way as a temporary frontier, behind which they were able to establish the Roman way of life. Figure 2 shows the main roads built in Britain by the Romans. The names they bear are not those which were given to them by the Romans, but the ones which have come to be attached to them during the course of centuries. One of the main purposes they served was to ensure rapid communications with the north of England, where there was always danger of trouble from outlaying tribes which were evading Roman rule.

Milestones found at various points tell us a good deal about the history of the roads. They were always inscribed with the name of the reigning emperor, and of the legion responsible for the building of the road. The inscriptions help us to know approximately when the roads were built, and also where the legions were posted. As the roads were built for military rather than civilian use, they sometimes have very steep gradients. At intervals of about 25 miles along the main roads stood posting stations, where horses were kept for carrying official letters. This system provided a highly efficient postal service.

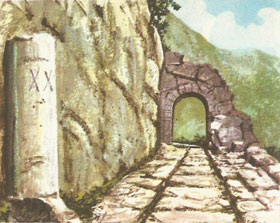

Roman roads frequently had to climb in order to reach passes in a range of mountains. Figure 4 shows a stretch of the road which runs from Italy into France across the little St. Bernard Pass. To make this stretch of the road 150 yards of rock had to be excavated. The illustration shows at the far end a Roman arch which is still standing and on the left is a milestone.

|

| Figure 4. The remains of a Roman road in the Alps. On the left can be seen a Roman milestone.

|

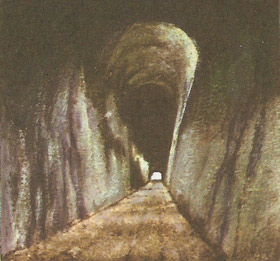

Roman engineers were undaunted even by the problem of having to excavate a tunnel in rock. Nobody looking at the tunnel shown in Figure 5 would guess that it had been built more than 2,000 years ago, before the invention of pneumatic drills and gunpowder. It shows the tunnel built by Augustus between Cumae and the Lake of Avernus. It is 600 yards long and is illuminated by light coming through slanting cuttings. The name of the engineer of this remarkable construction is Lucius Caccius Auctus, as we learn from an inscription. The length of this tunnel is not, however, a record in Roman engineering. When Claudius drained the Fucine Lake, he built a tunnel at least three miles long through a hill.

|

| Figure 5. The tunnel bored by Romans between Cumae and the Lake of Avernus.

|

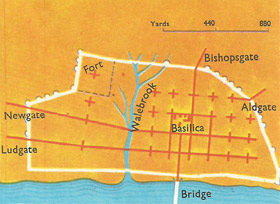

The map of Roman London in Figure 6 shows the care the Romans took in planning of the towns they built. The roads all run at right angles to each other, and in military forts, such as York, the design was even more rigid. The destruction of London, and its subsequent rebuilding on a less carefully thought out plan, has meant that all traces of the ancient streets have disappeared. Some towns on the continent of Europe have preserved more of their original Roman design.

|

| Figure 6. The street plan of Roman London shows how Romans planned cities.

|

The tombs and monuments of citizens were sometimes built on the first stretches of a large road as it left the city. This gave the road an impressive and dignified appearance (Fig 3). One of the reasons for this custom was that only in very exceptional circumstances was anybody allowed to be buried within the walls of Rome. The picture is imaginary, but a number of the original paving stones are still there. Tombs and monuments lining the first stretch of a road outside the city walls.