Romanesque art of the 11th century

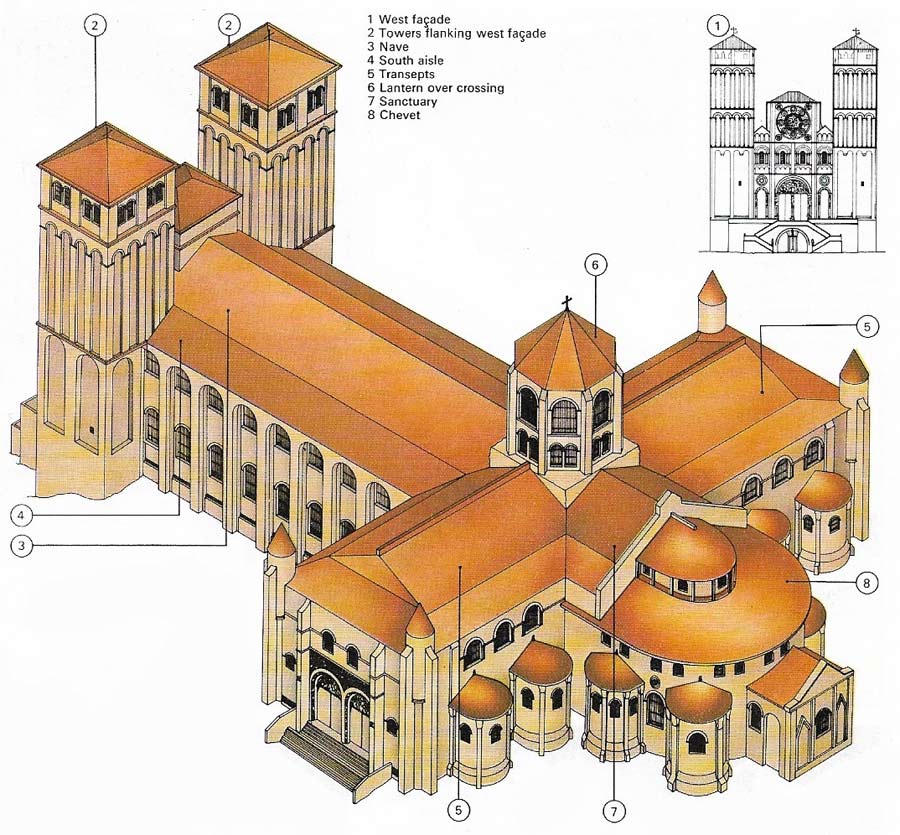

Figure 1. The cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain is the reputed burial place of the apostle James and was the goal of vast numbers of pilgrims from allover Europe during the Middle Ages. Four main "pilgrimage roads" from France fed a single route through northern Spain, each road being marked by an important shrine. The five greatest churches built between 1050 and 1100 were at Tours (St Martin), Limoges (St Martial), Conques (Ste-Foy); Toulouse (St Sernin), and Compostela. They have similar plans and were influential in spreading the concept of the great Romanesque church – a large, cross-shaped building with a towered main western entrance (1, 2), galleries round the interior at an upper level, and emphasis on the east end with many protruding apses for altars. The nave (3) had altars, but served mainly as a congregating area. Each altar was dedicated to a different saint and had a reliquary on or within it. Candelabra, screens, and hangings were placed around the altar. (It was this profusion of fittings that fed accidental fires.) This is the third church on the Compostela site, probably built by French masons and finished c. 1125, although many alterations have since been made.

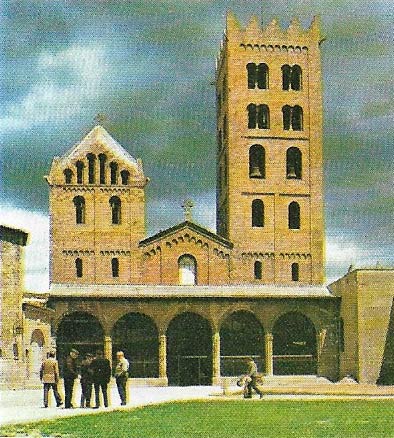

Figure 2. The west facade of the monastic church at Sta Maria at Ripoli near Genoa was rebuilt between 1020 and 1032 by Abbot Olivia. This style of church can be seen throughout southern Europe and is distinguished by the use of small rubble building material, the covering of all interiors with vaults, and, particularly, by the arched corbel-table running around the summit of all external walls – seen here on the towers and gable.

Figure 3. In the church of S Angelo in Formis, near Capua (rebuilt after 1072), this picture shows Christ touching the eyes of the blind man, who then washes at the well and sees again. Spots on the cheeks and angular drapery patterns show the Byzantine influence. The painting illustrates scenes from the Old and New Testaments and cover the whole interior of the church. Such a complete cycle is rare today.

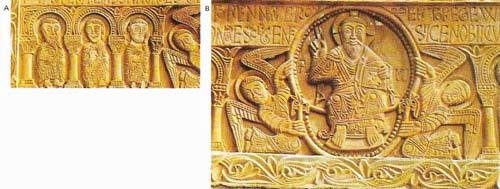

Figure 4. The marble lintels at St Genis-des_fontaines, French Pyrenees (1020–1021), show the enthroned Christ (B) supported by angels. Saints (A) flank the figure. It is one of the earliest known pieces of monumental medieval stone sculpture. The layout and the light chip carving indicate that the sculptors had studied earlier stone reliefs and contemporary metalwork such as Basle altar-frontal.

Figure 5. This large altar-frontal of beaten gold was given to Basle Cathedral by the German emperor Henry II (c. 1019). The central figure of Christ is flanked by the archangels Gabriel and Raphael on the left, and S Michael and Benedict on the right. Henry and the Empress Kunigunde kneel at Christ's feet. Few large precious-metal objects have survived from the early periods. Their value as metal tempted later generations to melt them down.

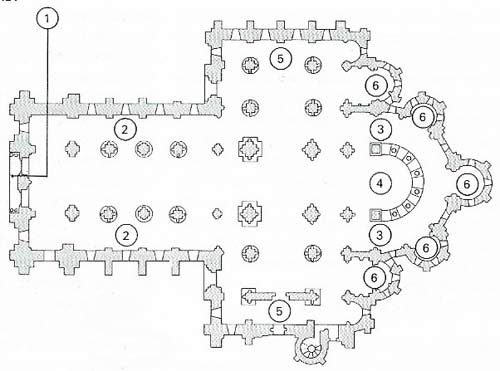

Figure 6. This ground plan of Sainte-Foy, Conques, France (c. 1050–1110) allowed for the needs of pilgrim and monk alike. The former would enter at the west (1), and go along the aisles (2) to the ambulatory (3) to look at the principal shrine in the sanctuary (4). The monks would enter the church by the transept (5) from the cloister (around which the monastery was grouped), and then go in procession to their choir behind screens or to minor altars (6).

The term "Romanesque" was borrowed from literary sources by nineteenth-century antiquaries to describe pre-Gothic architecture, implying that it reflected that of Rome. Today it is applied to the art, and more especially the architecture, of the 11th and 12th centuries. The political and economic instability of Western Europe after the abandonment of the Western Roman Empire accelerated the decline of widespread patronage of the arts. Despite the glories of the artistic revival under the emperor Charlemagne and his successors, and personal patronage in more localized centres, it was only the reestablishment of strong governments and the parallel reforms within the Church c. AD 1000 that caused the arts to revive throughout Europe.

|

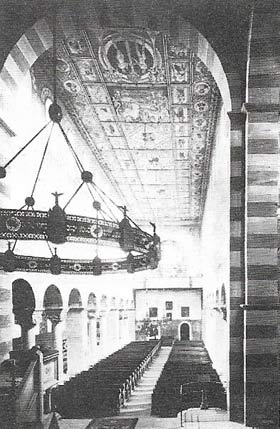

| The nave of St Michael's, Hildesheim(1000–1033) (looking west) has a 12th-century wooden ceiling and the original suspended candelabrum to light the eastern crossing. The church has no vaults, in the Carthaginian tradition, and so is wide and well lit. The solid walls of the elevation are now dull and monotonous, but they were once brightly painted, possibly to emphasize the width. |

Patronage of the arts by the Church

Land was the primary source of income in the Middle Ages, and the power of landowners was supreme. The Church readily accepted gifts of land and became a great feudal land-owner, owning as much as a third of France in the eleventh century. The other source of income was the offerings of the faithful at saints' shrines, and pilgrimages to them were common for people of all classes.

|

| The gold-covered cult-figure of Ste-Foy was originally made in the 10th century, but pious visitors to her shrine at Conques have, over the centuries, encrusted this reliquary with precious stones, cameos, and crystals. Although other figures were made, a statue was considered idolatrous and most reliquaries are casket or shrine shape and contain the saint's relics. Sometimes a representation of a particular part of the holy body is on top. |

Although Rome and Santiago de Compostela in Spain were the major destinations, visits to many other centres were encouraged. The shrines contained holy relics which were believed by many to have great healing powers. To display them in safety was an incentive for rebuilding a church. The creation of monastic orders – particularly the Cluniacs – to protect these relics and the founding of monasteries to administer both spiritual and temporal affairs also encouraged building.

The Church therefore became the greatest patron of the arts, building religious houses, decorating them with paintings (Figure 3) and hangings and filling them with altars, candelabra and screens made of wood or iron. As religious services grew more elaborate, more manuscripts and religious artefacts were acquired. Stone castles and houses from this period are rare, which may indicate that they were not built in great numbers or, more likely, were soon replaced by better and more comfortable structures. The creation of a church for both pilgrim and monk was the builder's main problem.

Romanesque churches of two forms

Two basic church types were current in Western Europe: the wooden-roofed, aisled basilica, and the vaulted small-scale martyrium (erected on a site of religious significance). The former had been taken up by the early Christians in Rome and continued to flourish with little development in central Italy up to the Gothic period. When Charlemagne and his successors sought to revive the Roman Empire from c. AD 800, it was this type of church they copied in Germany.

These churches had apsidal choirs, sometimes at both ends, with west fronts forming multi-storied masses, called westwerks, and they were crowned at each end with towers. Linking these complex elements was the long nave, with expanses of flat wall between the ground-floor arcades and upper windows. These areas were painted or hung with embroideries. All Romanesque churches were a mass of color, now lost.

In central Italy, no such evolution took place. Marble panels were often used instead of wall-paintings in Tuscany, as at San Miniato at Monte, Florence, and bell-towers and baptisteries were usually completely detached, as is seen most clearly at Pisa.

The martyrium type is not so easily identified as the Roman, although its distribution corresponds to the extent of the Roman Empire in the fifth century – that is, north and east Spain, the southern half of France, north Italy, Yugoslavia and Asia Minor. Its roots lay in the provincial Roman buildings, built of small local stone or brick rather than the faced stone blocks of imperial monuments. Although limiting size, this material facilitated the vaulting of the narrower spans, in contrast to the open wood roofs of the wide basilica-church.

As a consequence, however, the mason became a craftsman in stone rather than a sculptor, and any architectural sculpture, such as capitals, was often crude and carved in relief rather than deeply cut into the stone. Apart from the materials used, the decorative system of thin pilasters (ornamental rectangular columns) rising to a corbel-table (a line of projections running along under the eaves) clearly distinguishes this work.

Romanesque churches in provincial France

These two church types merged, and after much experiment (especially in France), two basic plans evolved, which were modified in each region to suit local conditions. The great pilgrimage churches (Figure 1) are typical of the "ambulatory" plan, which allowed pilgrims to see the relics behind the high altar – or beneath it in a crypt — without disturbing the monks at their worship (Figure 6).

|

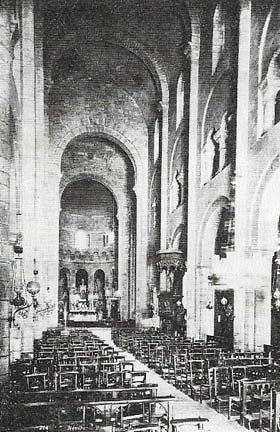

| The nave of Etienne, Nevers (c. 1070), looking east toward the high altar, is made narrow and dark by the need to support the stone barrel vaults. Behind the middle range of arches a half-barrel links the main elevation, helping o support the main span and allowing for small upper windows, The wall shafts divide the elevation into vertical rather than horizontal bay units. |

Churches associated with the Cluniac order, especially in Burgundy, used parallel apses, that is, a series of semicircular or octagonal recesses of varying heights and depths flanking the main monk's choir. Unlike the ambulatory layout, this plan probably encouraged masons to vault the main areas, as more solid walls were available for support. Lighting such vaulted spaces was a difficulty that was not satisfactorily overcome until the widespread use of cut-stone (ashlar) in the second half of the 12th century.