Russia in the 19th century

Figure 1. Following the capture of Sevastopol and her defeat in the Crimean War, Russia became little more than a second-rate power. Britain and France had turned against her and expose the backwardness of her economy and the brittleness of her army. The new tsar, Alexander II, was convinced that Russia had to imitate the Western powers if she was to beat them and so he favoured sweeping reforms.

Figure 2. Peasants received insufficient land as a result of the Emancipation Act (here being read out to Georgian peasants). They did not receive land freely, most of them having to pay a fixed annual amount to the state which in turn compensated the landlords with state bonds. Repayments were to extend over 49 years and were higher than the market value of the land warranted. The result was that the peasants had less land than before – in fact about 20% less in total – 23% of this in the black earth lands and 31% in the Ukraine. Former state and crown peasants received the best terms.

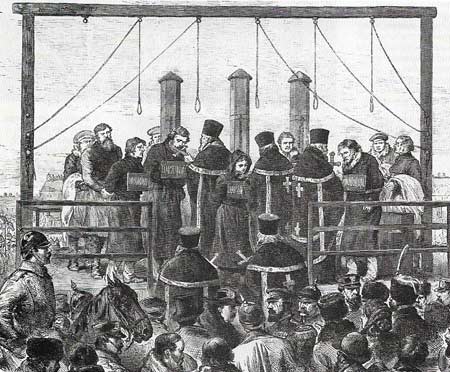

Figure 3. The execution of terrorists who planned the assassination of Tzar Alexander II by a bomb in March 1881, in the hope that the whole imperial edifice would collapse, sums up the importance importance of revolutionary politics in 19th-century Russia. The acute disappointment felt by the peasants and intelligentsia after the Emancipation Act led to pessimism concerning the possibility of reform from above. Many radicals, known as populists or agrarian socialists, believed the peasantry would rise en masse and sweep away the hated autocracy. Some believed in the gradual awakening of peasant consciousness, molded by radical idealists. Others were unwilling to wait for the uprising of the masses and adopted terrorist methods.

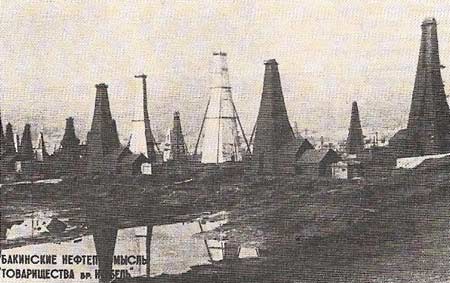

Figure 4. In the 1890s the industrial development of Russia was improved by the opening up of new oil fields, including this one at Baku. Russia was the world's largest producer of oil until 1900, when the USA took the lead. Railway building was another dynamic force; by 1874 there were 18,220 kilometers (11,320 miles) of railway. A by-product of this was Russia's emergence as a major grain exporter. From the 1880s the state began to play an important role in the economy, guided by the policies of Sergei Witte. Development was concentrated in railway construction and in heavy industry.

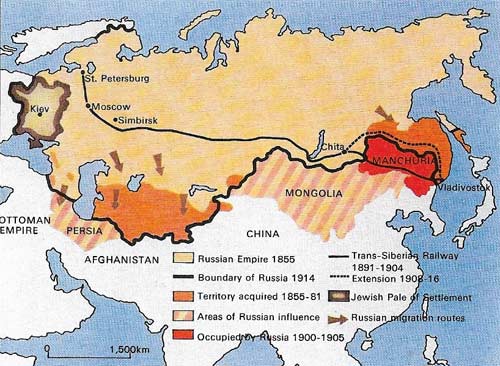

Figure 5. Russia's imperial advance was spectacular in the later 19th century. She colonized Central Asia and acquired territory which the Chinese still claim as their own. Russia's population explosion caused seven million peasants to move eastwards and cross the Urals. Meanwhile two million Jews emigrated to the USA and 200,000 more to Britain between 1880 and 1914. The Trans-Siberian Railway (built between 1891 and 1904) made a more active policy feasible in the Far East – that is, towards Japan – with the secondary aim of securing an ice-free port on the Pacific. Russia's eastward push and her influence in Manchuria alarmed the Japanese to the point of their going to war in 1904. Apart from her Far Eastern ambitions, Russia also greatly extended her influence in the regions on her southern borders.

Figure 6. "Bloody Sunday" began as a peaceful demonstration on which troops opened fire in St Petersburg on 22 January 1905. Discontentedly had grown as the industrial boom of the 1890s gave way to a slump during the early years of the 20th century. Harvest failures aggravated the problem compounded by the defeat in war with Japan. Although unsuccessful, the subsequent revolution of 1905–1906 did produce a constitution and a parliament (Duma).

Figure 7. Servile labor was typical of the life of millions of Russians in the 19th century, but with industrial development and the population explosion, changes occurred. There were 412,000 barge hauliers on the Volga in 1830, but by 1851 this number had been reduced to 150,000. The steamship had gradually replaced them. There were approximately 40 million peasants (80% of the population) in Russia on the eve of emancipation and about half were in personal bondage to the gentry. Their plight dominated economic life in Russia.

In Russia, since the time of Peter the Great (1672–1725), fundamental reforms have followed in the wake of war. For many years after the Crimean War (1854–1856) (Figure 1) Russia was no longer regarded as a friendly power by Britain and France. Despite the fact that it had the largest land forces on the continent of Europe this war showed that Russia was no match for the Anglo-French alliance and that its effort to insulate itself from the political changes in the rest of Europe had proved to be a source of weakness rather than of strength. Finally, its economy and social order could not withstand the war. Russia if it wished to regain its position as a leading nation, had to imitate the Western powers and adopt their forms of government.

The emancipation of the serfs

Alexander II (1818–1881), who came to the throne in 1855, was willing to introduce reforms. He warned the nobility that if reform did not come from above it would come from below. In February 1861 the Emancipation Act was ready.

The Act ensured personal freedom for millions of peasants and introduced the elective zemstvo, an organ of local government, which was to have an important say in the countryside. Other major reforms followed: in 1864 equality before the law, trial by jury and independence of courts and judges were introduced; legislation of 1863 and 1864 broadened the basis of education; the 1870 Government Act set up new municipal institutions; the 1874 army reforms established the principle of universal military service and reduced actual service from 25 years to six. But the peasants were still subject to customary law and had special courts; their freedom of movement was limited and they still paid poll taxes. Moreover, the Tsar did not grant a parliament.

The emancipation disappointed most of the peasants and their supporters. Population increased from 70 million in 1863 to 155 million in 1913 (excluding Finland and Poland), aggravating rural poverty. Migration eased the situation slightly, but the problem of land hunger was exacerbated by the failure to introduce modern agricultural methods, obstructed by the communal system of land ownership. Much peasant dissatisfaction also stemmed from the poor quality of the land that they were allotted, and the high level of repayments they were forced to make to the government to compensate the former owners of the land.

Seeds of revolution

The inadequacy of Alexander's reforms aroused moral revulsion and anger among many sons and daughters of the gentry and others who had acquired some education. Disillusionment over the reforms at first encouraged nihilism. The nihilists believed that the existing order could not successfully reform itself and in Russia they contributed significantly to the tradition of revolutionary political movements. During the 1870s a more positive populism or agrarian socialism developed which glorified the peasant as the repository of pure, untainted wisdom. Those who had received an education felt that they owed a debt of gratitude to the toilers who had made it possible.

|

| Populism became the leading philosophical attitude on the 1870s. Its most significant leader was Peter Lavrov (1823–1900). Populism rejected the Industrial Revolution and favored rural life. |

Agrarian populism was difficult to convert into political action and the onset of industrialization in the late 1880s and the boom of the 1890s made it less relevant. Marxism, placing its faith not in the rural worker but in the urban, industrial worker, became a doctrine more in tune with contemporary Russian conditions. The Social Democratic Party, the forerunner of the Communist Party, emerged, although it still appealed for the most part to intellectuals rather than to the working classes.

|

| Georgy Plekhanov (1857–1918), the father of Russian Marxism, started his political life as a populist. He opposed terrorism, but had to flee the country for Geneva in 1880 during a wave of political repression and did not return to Russia until 1917. A brilliant writer and polemicist, his influence within Russia in the 1880s was immense. He initially supported Lenin, then opposed him. |

The terrorist wing of the populist movement finally resulted in the assassination of Alexander II. But instead of collapsing, the autocracy struck back at its tormentors.

The end of the era

Alexander III (1845–1894), who came to the throne in 1881, was ultra-reactionary. His policies reversed many of the liberal reforms of his predecessor and began a tradition of conflict between the zemstvos and central government that came to a head in 1905.

The succession in 1894 of Nicholas II (1868–1918) (8) occurred at a time of rapid economic advance [6]. The dynamic thrust of Sergei Witte (1849–1915), minister of finance from 1892–1903, kept the economy moving until the first years of this century. Then harvest failures and industrial crises produced civil unrest. The revolution of 1905–1906 shook the autocracy to its foundations (Figure 6). It could be suppressed only when the war against Japan had been lost and troops were released for internal duties.

|

| The last of the Romanovs, Nicholas II, was a reluctant tsar. He came to the throne unusually young and made an inauspicious start in 1894. His mind lacked the cutting edge necessary to evolve a coherent policy and to see it through. Although Russia changed rapidly during his reign he did not move with the times and listened instead to reactionaries, including the monk Rasputin (1871–1916) who mystically influenced the Empress. Here Nicholas (2nd from left) is with the Prince of Wales (far right). |

The years 1903–1913 were a golden era for industry and agriculture and this helped the government, led by Peter Stolypin (1862–1911), to resist the growing demands for political and social reforms, which were voiced in the Duma (a parliament forced on the Tsar by the crisis of 1905) by the Social Democratic and Kadet (liberal) parties. Thwarted in the Far East, Russia turned after 1906 towards the Balkans where, throughout the nineteenth century, it had supported Slav states against the decaying Ottoman Empire. But the Great Powers stepped in and blocked Russia's progress to the Mediterranean. The empire of Austria-Hungary was the main rival power in the Balkans and therefore Russia felt obliged to support Serbia against the empire in August 1914.

|

| An outstanding statesman, Peter Stolypin (1862–1911) introduced agrarian reforms. He swept away the commune and encouraged the peasants to consolidate their holdings and become farmers. But his autocratic methods lost him liberal support. |