rise of medieval Western Christendom

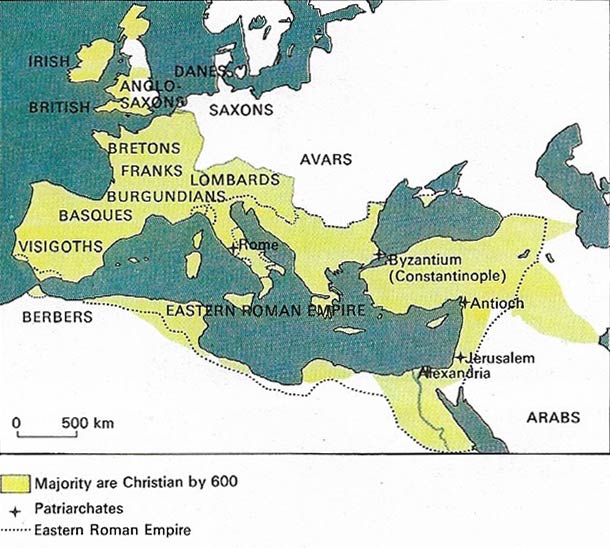

Figure 1. Orthodox Christianity in the later Roman world reached its greatest extent c. 600. North Africa, Rome and Ravenna were reconquered from the Arian Goths by Justinian in the mid-6th century. In the north, the Irish had been converted about 430, the Franks in 496, the Burgundians in 516 and the Visigoths in 589. The Anglo-Saxon missions began in 597. The new Christian unity of the Mediterranean, however, lasted only until the Arabs in the 7th century conquered an empire from Syria to Spain including three of the five original patriarchates, Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria.

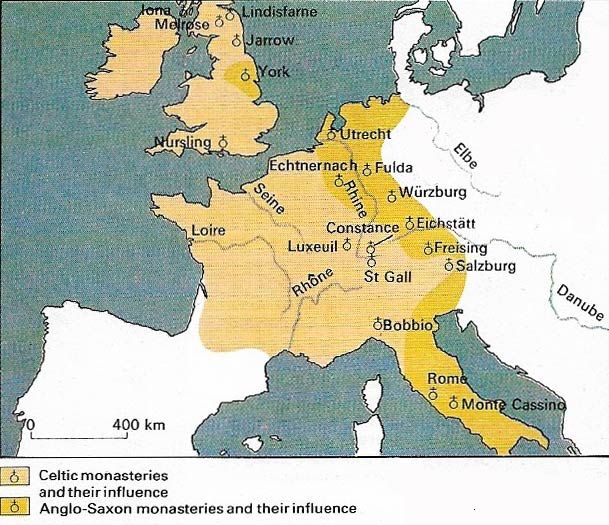

Figure 2. Many European monasteries were founded by missionaries from Ireland where Christianity and classical learning had been preserved. Others were founded by their Anglo-Saxon converts.

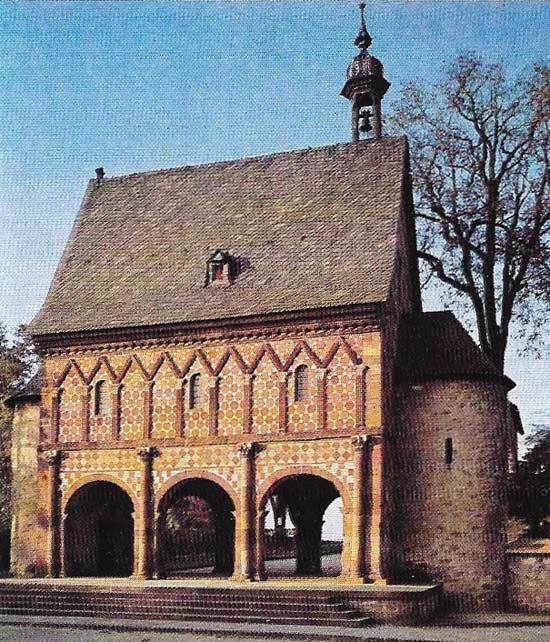

Figure 3. The Gatehouse of Lorsch Abbey, in Hessen, Germany, is an example of Charlemagne's impressive program of new church building.

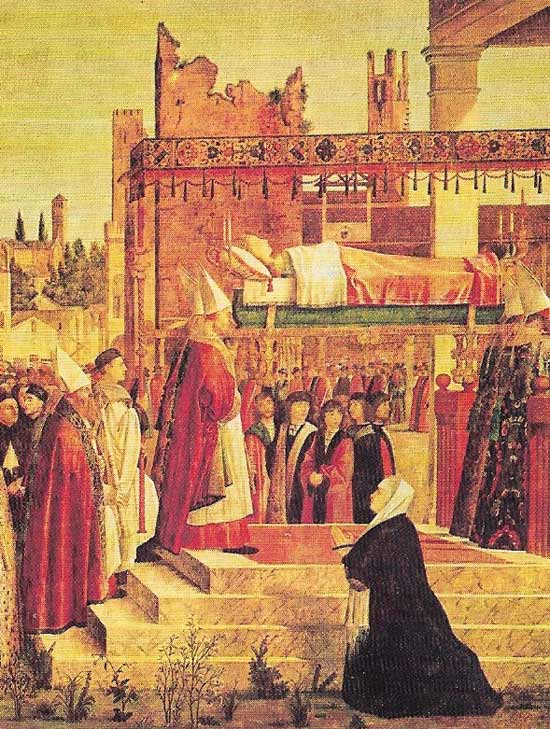

Figure 4. The story of the martyrdom of St Ursula is the most famous of the martyrdom legends from the barbarian period. The saint, together with her companions, was murdered by the Huns in Cologne in 454 still protesting her virginity and her faith. Her triumphal funeral is shown in a painting by Vittore Carpaccio (1490). The cult of local martyrs became increasingly important during the reconversion period, at which time the supposed number of St Ursula's companions was increased to 11,000 by a clerical error. A notable missionary martyr was St Boniface, who went to Frisia and was murdered at Dokkum in the mid-8th century with 30 other monks.

Figure 5. St Patrick, a Roman-Britain is credited with converting Ireland between 430 and 461. Ireland was the only country to escape the invasions of the 5th and 6th centuries. Christianity was preserved, along with many manuscripts containing both secular Latin and Christian literature. Irish missionary impetus was a prime factor in the re-education of Europe but its loosely ordered yet ascetic monasticism conflicted with the usages of the Roman Church after the reforms of Gregory the Great. This conflict was resolved at the Synod of Whitby (664) and led to period of peace which saw the creation of a British culture unrivalled in the rest of Europe.

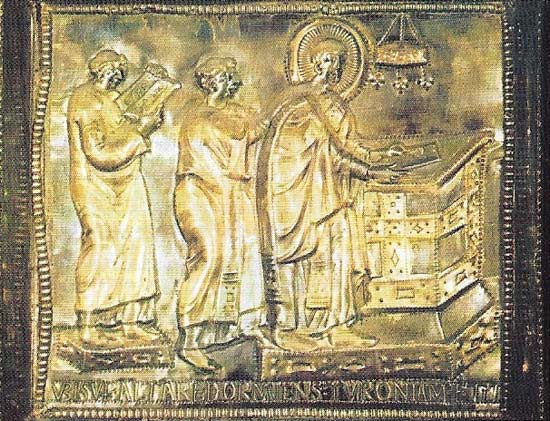

Figure 6. Relics became an essential part of the furnishings of every church in the 9th century. They were housed in the greatest magnificence. As in the High Alter of St Ambrose, Milan, decorated by the German Volfinius about 835.

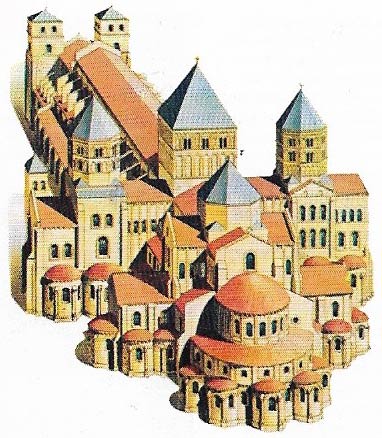

Figure 7. The Abbey of Cluny saw the start of the reform of the Benedictine system with a strict adherence to Rule and stress on the splendor of the liturgy. This is the third church at Cluny dedicated to these ideals.

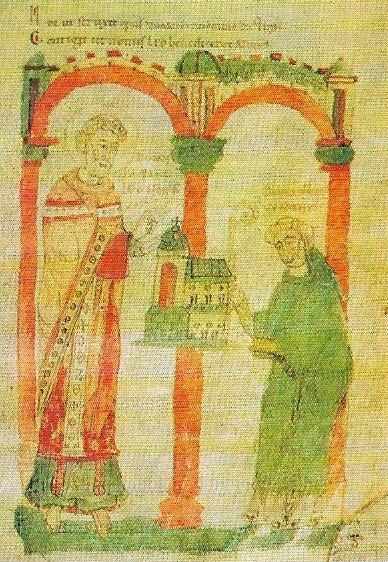

Figure 8. Leo IX, who was pope from 1049–1054, was an ardent supporter of Cluniac reform. He began to improve papal standards.

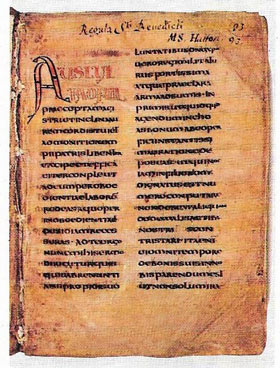

The barbarians who destroyed the Western Empires in the 5th and 6th centuries were either pagans or Arian heretics who denied the traditional Christian belief in the unity of God, Father, and Son so violently rejected Roman Christianity. By the 6th century a reconversion of Europe began. Missionary activity from Rome followed the growth of Benedictine monasticism and a rejuvenation of the papacy. St Benedict (c. 480–c. 547) lived in Italy when it was ruled by the Arian Ostrogoths. About the year 500 he had begun a hermetical life at Subiaco with emphasis on the performance of the liturgy and on a community life of moderate self-denial. In c. 529 he founded the Abbey of Monte Cassino, one of the bulwarks of Christianity and civilization in early medieval Europe. He also wrote A Rule for his monks that was humane and ensured the durability of his ideas and institutions.

|

| The Benedictine Rule was the cornerstone of the early medieval Church. It contained strict yet reasonable regulations for monastic life, in contrast to the ascetic excesses of Eastern monasticism. The Rule stressed the value of religious community life, humility, self-denial and the performance of the liturgy. For 600 years after Benedict's death in c. 547 there was no other monastic rule in the West. Its followers have included 20 popes and many pioneer missionaries. The learning and education of Benedictine monasteries in the Dark Ages also provided the only training for administrators faced with the increasingly complex problems of government. |

The Papacy – spiritual and temporal

The medieval papacy was founded by Pope Gregory the Great (c. 540–604), who was a firm supporter and propagated of monasticism. He became pope in 590, a time when the power of the Byzantine governors of Italy was rapidly declining and the Arian Lombards threatened to reduce the Papacy to little more than a Lombard bishopric. Gregory himself managed the Church estates in central and southern Italy, organized the defences of Rome, appointed governors of the leading Italian cities and in 592–593 made peace with the Lombards without reference to the Eastern Emperor. The Papacy henceforth existed as a temporal as well as a spiritual power in the West.

|

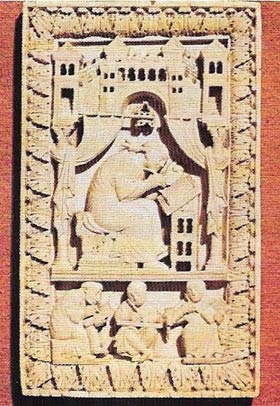

| Gregory I (center) was elected pope at a time when Rome was under strong pressure from the Arian Lombards. But his energy, dedication and grasp of administration enabled him to give the Roman Church a status it had never previously enjoyed. He established the principal of papal authority in temporal affairs both by his diplomacy initiatives and by asserting a control of the "patrimony of Peter" which later grew into the Papal States. By sending Augustine to England in 597, he made sure that the Church in Britain would look to Rome rather than Byzantium. Gregorian chant is named after him. |

The Franks were the first of the barbarians to be converted when Clovis (465–511), founder of the Merovingian monarchy, was baptized, probably in 497. Gregory dispatched St Augustine to England in 597 with monks from his own Roman monastery to begin the reconversion of Britain. But Britain was reconverted from two different directions because the Irish, who had remained Christian after the mission of St Patrick in 444 (Figure 5), had sent St Columba to Scotland c. 563 to found the monastery of Iona and convert the Picts. In c. 635 St Aidan went from Iona to Lindisfarne to convert the English in Northumbria. There the Roman and the Irish traditions met and the result was the most advanced and flourishing culture of seventh- and eighth-century Europe.

|

| The Ruthwell Cross, possibly either a mass preaching cross, is the finest monument of Northumbrian art during the British cultural renaissance of the 7th century. |

Anglo-Irish influence

The Irish also penetrated deep into mainland Europe (Figure 2). In 590 St Columba established monasteries at Anagratum and Luxcuil in the Vosges. Expelled from Burgundy for criticism of the behavior of the court, he went to Italy to found the monastery of Bobbio, which set an example that was the most important impetus to the conversion of the Lombards. These and other Irish monasteries reintroduced the Catholic faith and brought with them their libraries, both classical and Christian, which had remained safe in Ireland during the migration period. The influence of the Irish on European culture can hardly be overemphasized.

Frisia and Germany we're converted from Britain in the eighth century. Willibrord (c. 658–739), the apostle of the Frisians, was a Northumbrian who had joined a monastery in Ireland. Boniface (c. 680–754), an Englishman, continued the Frisian mission in 716, and in 719 was appointed by Gregory II to convert the Germans. He laid the foundations for the Carolingian Church and was martyred in Frisia in 754 (Figure 4).

The Arian Visigoths in Spain were converted to Christianity at the Third Council of Toledo in 589 (although Mishima invaders were soon to dominate the country). In northeastern Europe, conversions were delayed longer. Sweden and Denmark were only temporarily converted by St Anskar in the ninth century, Poland and Hungary in the late tenth and Norway at sword point by St Olaf early in the eleventh century.

In. The meantime the emperor of the Franks, Charlemagne (742–814), had imported Anglo-Irish missionaries to establish the basis of Carolingian Christianity, backed by energetic church building (Figure 3). The late eighth century also saw an alliance between the pope and the Frankish emperors against the Lombards and the creation of the idea of the Holy Roman Empire. Anglo-Saxons, Germans and Franks all visited Rome, accepted the lead of the Papacy and bought relics for their native dioceses (8).

The rise of the Holy Roman Empire saw a marked decline in the standards of the Church. There was widespread simony (the selling of ecclesiastical appointments), monasteries became rich and lax, and the Papacy itself was corrupt.

Church reform

Reform of the Church began at the house of Cluny, a Benedictine monastery In a Irgun dynasty (Figure 7). Under Abbot Odo the Benedictine Rule was strictly enforced. The spirit of Cluniac reform permeated all aspects of Western Christianity, culminating in the pontificates of Leo IX (Figure 8) and Gregory VII (1073–1085).

In 1054, the last year of Leo IX's pontificate, the Western Church broke with the Eastern. The Patriarch of Constantinople would not accept the universal supremacy of Rome, nor the people of the East the Liturgy and practice of the Roman Church. Leo IX and the Emperor sought a political settlement between East and West to thwart their common enemy, the Normans, but the rift in religious practice was too wide to heal.