Scotland 1314 to 1560

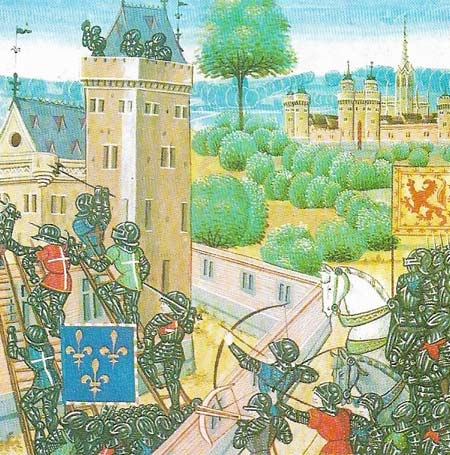

Figure 1. Scottish troops and their French allies are shown here attacking Wark Castle in 1385, one of the lesser English Border Castles. The “auld alliance” meant that Scottish forces frequently became involved in the Hundred Years War. This illumination is from Froissart’s Chronicles of the 15th century.

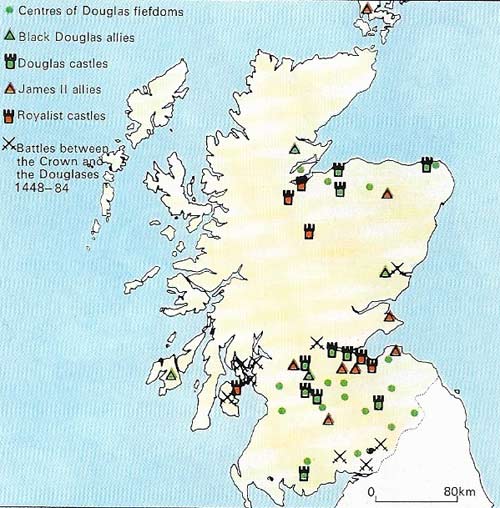

Figure 2. The Black Douglas family's conflict with a succession of Scottish kings well illustrates the struggle between the nobility and the Crown in medieval Scotland. During the 15th century the power of the Douglas family in the Border area posed a growing threat to the Crown until they were finally suppressed by James II.

Figure 3. James I succeeded to the Scottish throne in 1406 at the age of 12, when he was held captive by the English. He remained a prisoner until 1424 when he was released in return for a large ransom. He returned, determined to assert the power of the Crown and to give the Scottish Parliament an importance and authority similar to that of the English Parliament. Under his reign it introduced taxes, passed laws and reforms and supervised trade. A period of vigorous reform began that touched many aspects of daily life, extending the Crown's control. In 1426 a court for civil cases was created that sat three times a year to settle disputes.

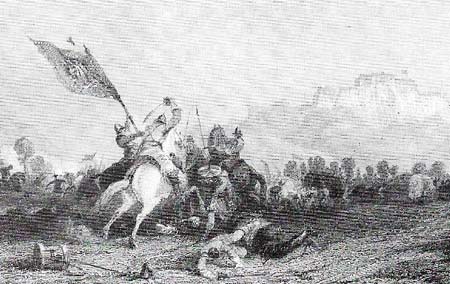

Figure 4. James III's reign ended with an armed rising of the nobility, his defeat at Sauchieburn near Stirling in 1488, and his murder after battle. This 19th-century print shows the battle with Stirling Castle, where James had in vain sought refuge, in the background. The nobles' rebellion was probably motivated more by James's personality than by his policies: he was suspicious, avaricious and unconcerned with affairs of state. The relatively short reigns of Scottish monarchs, often ending violently amidst intrigue and conspiracy, resulted in a series of long minorities, beginning with James I, that undermined royal authority. For 200 years no Scottish ruler succeeded to the throne as an adult.

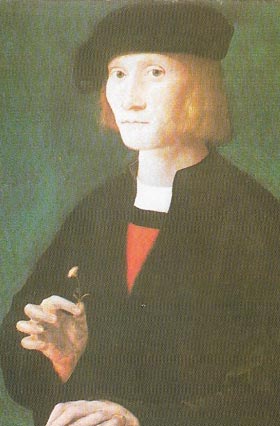

Figure 5. Margaret Tudor lacked the political drive and skill of her brother, Henry VIII, while sharing similar marriage difficulties. Thus, following the death of her husband, James IV at Flodden, her personal life was a considerable source of instability during the minority of James V. The man shown with her here is probably Duke of Albany (c. 1484–1536), who acted as regent until 1524.

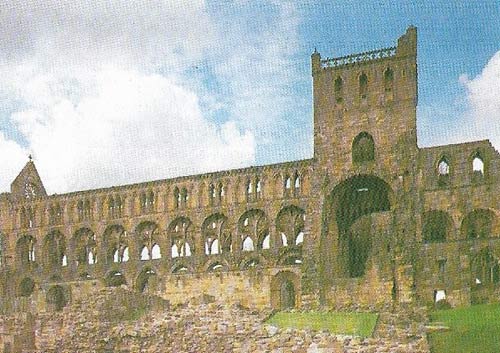

Figure 6. The Augustinian Border abbey of Jedburgh was one of the richest foundations in Scotland. During the 16th century it was burnt three times by the invading armies of Henry VIII.

Early in the War of Independence (1306–1314) against England, the Scots had made the "auld alliance" with France – an agreement between the two countries to act together against England. This alliance was renewed at various times during the next three centuries although it is doubtful whether it brought advantages to Scotland.

Conflict with England and the clans

Peace was eventually made some years after 1314, but as Edward III (reigned 1327–1377), the young English king, began to assert himself it ceased to be kept [Key]. In 1332 the English king allowed Edward (died 1363) the son of John Balliol (reigned 1292–1296), to try to reclaim Scotland from David II (reigned 1329–1371), the son of Robert Bruce. Defeat forced David to flee to France and the conflict became absorbed in the Hundred Years War between England and France. At various times in the 14th and 15th centuries Scotland became involved in this conflict.

|

| David II (left) was captured by the English at the battle of Neville's cross in 1346 which effectively ended his invasion attempt. The English king Edward III (right) held David prisoner for 11 years before freeing him in return for a large ransom. This proved to be a crippling burden for Scotland and taxes were greatly increased to meet the debt. The Scottish economy, already undermined by wars with England, was weakened still further, although over half the ransom money was finally paid. David also debased the coinage by minting more coins to meet the debt, a precedent followed by his successors – the first Stewart kings. |

In spite of frequent wars, which particularly damaged the trade of the principal Scottish towns – those in southern Scotland – the economy developed in this period, although the characteristic features of a primitive structure still adhered to it. From 1349 to 1350 the Black Death struck Scotland as it struck the rest of Europe and this plague returned several times, but because it became mainly an urban pestilence and Scottish towns remained very small, the country did not suffer greatly.

A more serious long-term development in the 14th century was the building up of the two branches of the great baronial family of Douglas, descended from Bruce's second-in-command, James Douglas (1286–c. 1330). This family became power-fully ensconced in the Border area, where at times it carried on negotiations or wars with English Border families as if it were an independent power. The Lordship of the Isles under the Macdonalds held a similar almost independent position in the Western Highlands and islands. Great independent aristocratic families could often supplant the king in the collection of his revenue and coerce and corrupt the local church, placing members of their own family into the better-paid ecclesiastical positions. Nepotism was not confined to the nobles, many kings also used the Church to provide regular incomes for their bastard offspring.

The power of the Crown

James I (reigned 1406–1437) was the first in a series of vigorous, often impetuous, short-lived kings who had a significant effect on the institutions of their country in their turbulent reigns. His reign saw the creation of Scotland's first university, at St Andrews, and the use of Parliament by the king as a means of gaining support from lesser folk in his struggle with the overmighty nobility (Figure 3). The king also began the process by which a professional central court, instead of the King's Council, was developed to hear cases. Under James V (reigned 1513–1542), this Court of Session obtained a more regular supply of money for the Crown by increased taxation. This provided funds for the Court – an important development towards professionalism in Scottish law.

James II (reigned 1437–1460) reduced the power of the Douglases by the extermination of the leaders (Figure 2). James IV (reigned 1488–1513) in 1493 attempted to increase royal authority in the Highlands by destroying the Lordship of the Isles. He was unable to replace this power with effective central rule, and the main result was to leave the Highlands broken into separate and often warring clans. Efforts by successive Scottish kings to have courts appropriate to Renaissance princes led to the cultivation of the arts by James III (reigned 1460–1488) (Figure 4) – who thereby annoyed his nobility – some splendid poetry in the reign of James IV and great spending by James V on royal palaces.

|

| One of the more attractive personalities among the early Scottish kings, James IV styled himself in the role of Renaissance monarch. He built new royal palaces, notably at Falkland and Linlithgow, and encouraged learning and the arts. But he was not successful in foreign affairs: in support of France, James Invaded England in 1513 but his army was defeated at Flodden Edge and he was slain. |

Protestantism established

James IV's marriage in 1503 to Margaret Tudor (1489–1541) (Fig 5), elder daughter of the English King, Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509), was of great long-term significance to both countries, for it led to the union of the crowns in 1603 and, even before that, in the later 16th century, to peace between them. But peace was not achieved at first. James IV was drawn into war with Henry VIII (reigned 1509–1547) in support of his renewed alliance with France. James invaded northern England and was killed in an overwhelming Scottish defeat at Flodden Edge in 1513.

In spite of this disaster the Scots clung to the French alliance, partly because of the ruthless attempt of Henry VIII to dominate their country. In particular, Henry hoped to marry his son Edward (1537–1553) to James V's daughter and successor, Mary. But James's marriage allied him to the rising family of Guise, who came to represent the Catholic party in France. Meanwhile the weaknesses and corruption of the Catholic Church and the political needs of the government encouraged the promotion of a powerful group of Protestant nobles.

|

| The formidable fortress at Stirling has played a major role in Scottish history, probably built in the 12th century. It was the birthplace and residence of several monarchs, rivalling the capital of Edinburgh. |

In 1560 the joint issues of external alliance and religion led to a brief war between the Catholic and French regent, Mary of Guise, and the Protestant lords in alliance with the English. The victory went to Protestantism and alliance with England, and this was confirmed in the Reformation Parliament of 1560, when the authority of the pope in Scotland was abolished.