Scotland to the Battle of Bannockburn

Figure 1. The Antonine Wall, the northernmost boundary of Roman rule in Britain, was built in the 2nd century AD. But even before the end of the century it had been abandoned by Roman forces under pressure from invading Pictish tribes. This monument, from where the wall meets the North Sea, shows a Roman horseman riding down four named tribesmen armed with spears, swords, and shields.

Figure 2. This defensive tower or broch, built of stones without cement, still stands more than 12 meters (40 feet) high on the island of Mousa in the Shetland Isles. Its thick walls offered a safe refuge from raiders and contained dwelling rooms and galleries. There are more than 500 known examples of brochs scattered along the coast of north Scotland,some dating back to the 1st century AD.

Figure 3. The impulse that David's founding of burghs gave to Scottish economic life is symbolized by the fact that his were the first coins to be minted by a Scottish king. Under his administration, trade and commerce flourished.

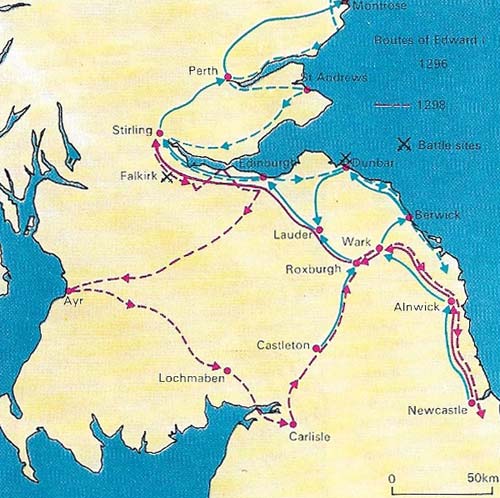

Figure 4. In 1296, Edward I invaded Scotland to put down Balliol's rebellion. After sacking Berwick and Dunbar he easily took other castles and towns, but resistance continued to the end of his reign in 1307.

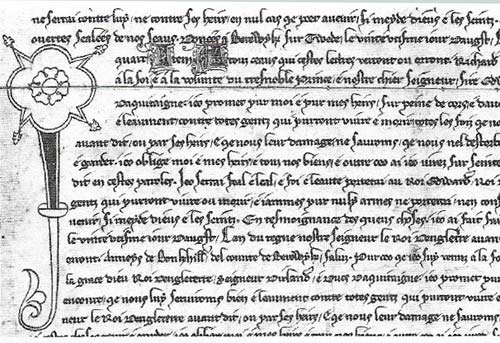

Figure 5. The "Ragman Roll" records those Scottish nobles and landholders who swore loyalty to Edward in his campaign of 1296, recognizing him as their king. Robert Bruce appears on it but not William Wallace. Later Bruce was to join Wallace in his unsuccessful rebellion, submit again to Edward, and finally rebel again and emerge victorious at the Battle of Bannockburn.

Figure 6. Robert Bruce was crowned King of the Scots in 1306, but within three months he had been defeated by an army sent by Edward I. It was not until 1309 that Bruce had gained enough power to hold a parliament – then his guerrilla tactics were gaining the upper hand against the English forces.

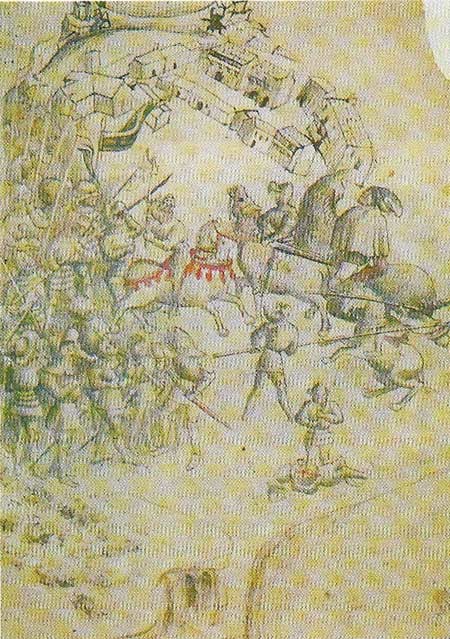

Figure 7. The Battle of Bannockburn was a resounding victory for the Scottish forces under Robert Bruce. The two sides met as the English troops attempted to relieve Stirling Castle. But Edward II, unlike his father, was neither a good general nor a man of determination, and the Scots, outnumbered three to one outmaneuvered the English.

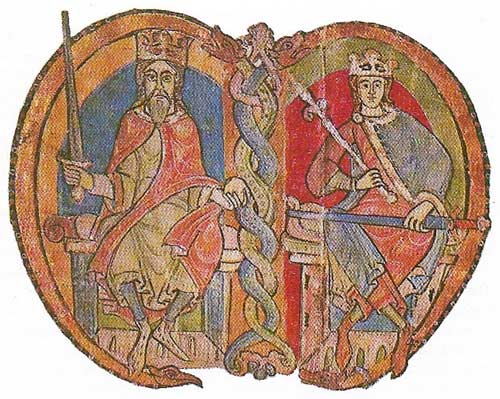

Figure 8. David I (left) and his grandson Malcolm IV, who succeeded him as a young boy, are shown on this 12th-century abbey charter. With David's death, the country had been transformed through the widespread introduction of feudal, Anglo-Norman ways of life, a policy continued under Malcolm. David had to have Malcolm proclaimed as his rightful heir because there wee other claimants to the throne by earlier rules of succession.

The Romans attempted to protect their British province by extending their power amongst the Pictish tribes beyond the frontier. For a while, in the 2nd century AD, they occupied the south of what was later called Scotland and built the defensive Antonine Wall across the narrow waist between the Forth and the Clyde (Figure 1).

The foundation of Scotland

In the sixth century "Scots" from Ireland crossed the narrow sea and began to settle among the scattered tribal communities of Picts, founding the kingdom of Dalriada in what is now Argyll. Eventually in the 9th century, by a mixture of royal intermarriage and conquest, the Scottish king Kenneth MacAlpin (died 858) became king of both Scots and Picts, and his successors extended this kingdom to include the area of Strathclyde, occupied by Britons, and of Lothian, where there were also Anglo-Saxon settlements. The Picts disappeared from history and the Scots spread their language, Gaelic, over most of their new kingdom, from then on to be called Scotland.

The kingdom was Christian, for the Scots had come from Christian Ireland and the Picts had been converted, partly by the mission of St Columba (521–597). It did not include all of modern Scotland, for the northern and western islands, Caithness and parts of the southwest were held by a new group of invaders, the Vikings from Scandinavia. These men had started raiding in the late eighth century, and made settlements in the ninth. Their mark in Scotland survives in place-names, and ruined buildings. It was not until the mid-1200s that a Scottish king, Alexander III (reigned 1249–1286), defeated a king of Norway and took over the western isles. The northern isles remained under Scandinavian rule until the fifteenth century.

|

| Iona church stands on the former site of St Columba's monastery (founded in 563). It was from here that Christianity was first carried by Columba to the Scottish mainland. |

The monarchy and feudalism

The monarchy gradually developed its own institutions. For a time the succession moved between two related lines of kings, but with the succession of Duncan I (died 1040) in 1034 an attempt was made to confine it to a single direct line. Duncan was defeated by his rival, Macbeth in 1040, but his son Malcolm III (c. 1031–1093) regained the throne in 1058 and established direct succession. Malcolm married Margaret (c. 1045–1093), an English princess, initiating two centuries of frequent royal marriages between the two countries. Their youngest son, David (1084–1153) (Fig 3), who became king in 1124, had spent much of his youth in England and held the earldom of Huntingdon. As King of Scotland he brought some Norman barons and friends from England and settled them in fiefs in southern Scotland. His long reign is important not only for this but also for the start of medieval monasticism in the country.

Succession was still not entirely assured, so to ensure peaceful inheritance David, when his only son died, took his 11-year-old grandson Malcolm round the kingdom to be proclaimed as his heir (Figure 8). Malcolm IV (reigned 1153–1165) and, following him, his brother William the Lion (reigned 1165–1214) took David's policy of feudalization further, and William spread it to central and northern Scotland. Feudalism provided the kings with mounted knights in time of war and established clearly defined obligations. The new office of sheriff gave them administrators for a wide number of tasks. The founding of monasteries brought Scotland into the important religious movement of the twelfth century.

In spite of close marriage ties and cultural links with England, and the fact that some Scottish barons held land in England too, peace between England and Scotland was not firmly established. The border between the two long remained unstable; under David I, Scotland controlled Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland. Its claim to these countries was formally abandoned only in 1237. Successive kings on one side or the other of the border attempted to enlarge their kingdoms by conquest.

Rebellions and the War of Independence

The male Scottish royal line ended with the sudden death of Alexander III in 1286. It was arranged that his Norwegian granddaughter should succeed and be married to the son of King Edward I of England (reigned 1272–1307). On her death in 1290, the Scots left the decision about the succession to Edward. He chose John Balliol (reigned 1292–1296), the best claimant by feudal law, but attempted to dictate to the new king. This led to an unsuccessful rebellion in 1296 (Figure 4), invasion by Edward [6], the resignation of Balliol and the removal of the Stone of Scone – on which Scottish kings were enthroned – to Westminster. For a time Scotland appeared to be conquered. But in 1297 a knight, William Wallace (c. 1270–1305), launched another and more serious national rebellion, which was not suppressed for several years. In 1306 came a third rising, ultimately successful, by Robert Bruce (1306–1329) (Figure 6), whose grandfather had been a claimant against Balliol in 1291. In the long War of Independence, Bruce taught the Scots how to avoid pitched battles, dismantle castles and rely on the inability of the English to sustain an army for long so far from home. Finally he defeated Edward II (reigned 1307–1327) in the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1314 (Figure 7). English claims to Scotland were not ended, and the two countries were often at war during the next three centuries, but Scottish independence was proved at Bannockburn.