Sub-Saharan Africa 1600 to 1800

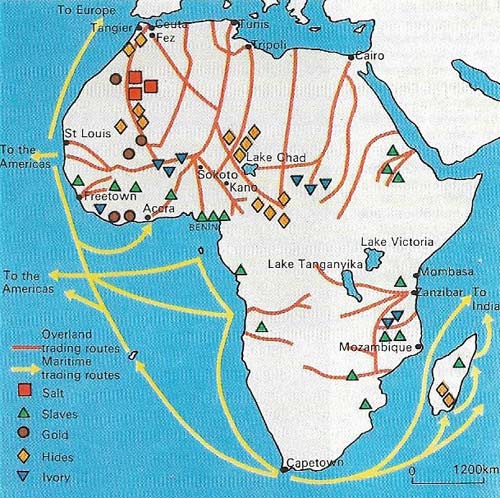

Figure 1. Although Africa was a major source of various goods, it was primarily the slave trade that established its link with the outside world as well as encouraging trade routes from within it. There was a steady flow of slaves to Muslim lands but most were shipped from west and west-central Africa for labour in the New World.

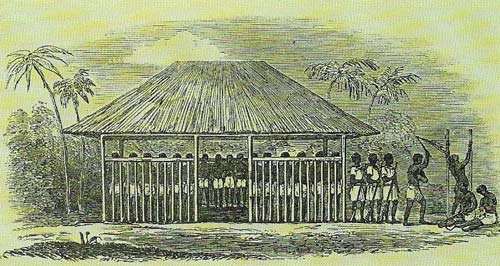

Figure 2. Before they were shipped to the New World slaves were assembled in barracks or "barrancoon", where they were treated much as any other freight for shipping. The slave trade was so lucrative that European traders made little effort to develop large-scale trade in other commodities until the 19th century.

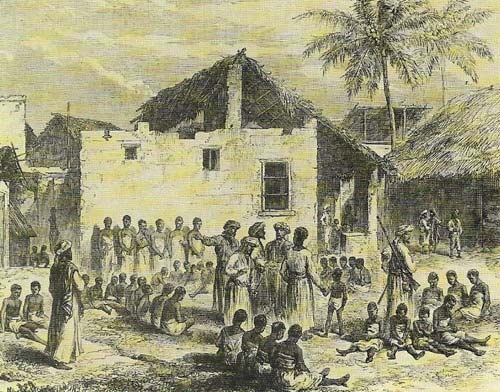

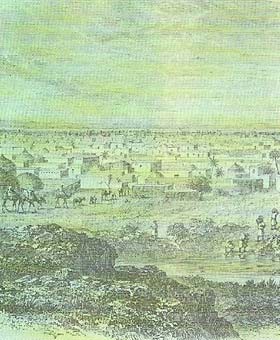

Figure 3. The great slave market at Zanzibar became the center of Arab trading on the east coast after the Portuguese evacuation at the end of the 17th century. Here the Arabs traded with the native rulers who raided and enslaved their weaker neighbours to exchange them for guns and cloth.

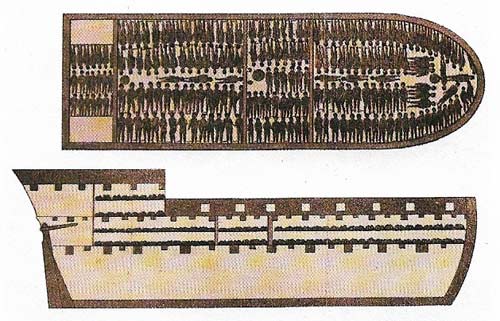

Figure 4. The inhuman disposition of a human cargo is shown on this plan of the Brookes, a vessel of the late 18th century. The Atlantic crossing, the notorious Middle Passage, took a terrible toll of lives and was not as profitable as the sugar, cotton and tobacco carried back to Europe.

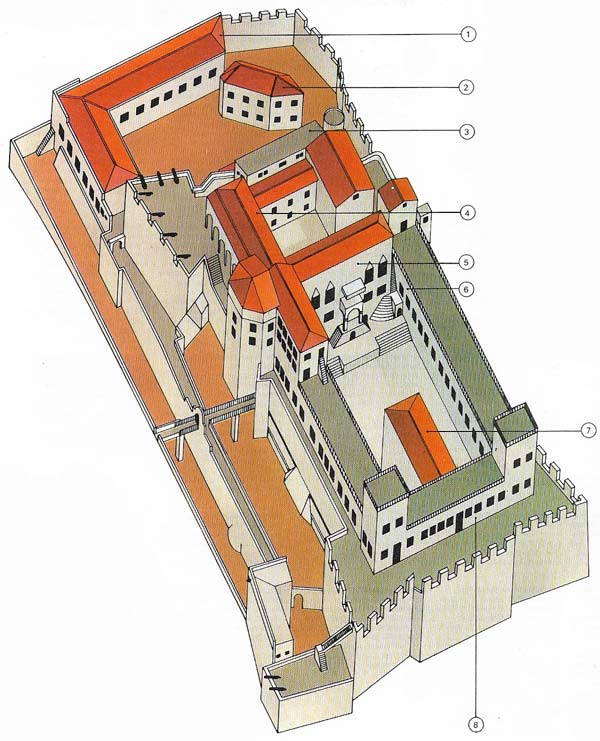

Figure 5. Fortified trading posts (called factories) were built by Europeans on the West African coast. The first factory was Portuguese, built at Elmina on the Gold Coast in 1481. Its name, "the Mine", reflected the first major export – gold. It became, however, like most factories, a slave-trade base. Conceived as a township with the fortifications of a castle, the principal buildings were the storerooms, accommodation and smithy (1); artisans' quarters and workshop (2); carpenter's shop (3); governor's hall (4); governor's residence (5); storerooms and accommodation (6); church (7); and hospital (8).

Figure 6. King Agaja (c. 1673–1740), ruler of the Fon kingdom of Dahomey, which had its origins on the mid-17th century, controlled a powerful state. He was able to press many people into its service, including these famous units of women soldiers, in the drive to establish the state against its rivals.

The appearance of a Portuguese fleet off the west coast of Africa in the mid-fifteenth century marked a new and decisive stage in the history of the continent: the beginning of a long and tumultuous relationship between Africans and Europeans. The Portuguese were followed by the Dutch in the 16th century and then by British, French and other Europeans a century later.

|

| Foreign influence – Muslim from the northern interior and European from over the sea – was a striking feature of African history between 1500 and 1800. African societies proved to be flexible but discriminating about these influences, a capacity reflected in their art. The kingdom of Benin, founded about 1400, was a rich source of art, mainly producing bronze sculptures similar to the figure shown here. Benin sculpture was based on a tradition that was more than a thousand years older than the kingdom itself, but the artists managed to assimilate influences from Western culture without departing from this venerable tradition. |

Complementary systems of trade

The many trading posts which these Europeans established on the coast, and linked to the Europe-based worldwide system of trade, complemented an existing trans-Saharan commercial network. This had been operating for at least 500 years and was forged between Arabic-speaking people from North Africa and black Africans living south of the Sahara. However, the European and trans-Saharan commercial systems were separated by the vast distances of the West African hinterland and never clashed. A surprising feature of this period in view of these twin commercial presences is the relatively little influence which these foreign cultures had on Africa as a whole. Many Africans in the Sudanic belt had become Muslims in the 500 years of Arab trading in North Africa – a process that set up stresses in African societies and eventually provoked the Holy Wars of the 19th century. These states continued to look north to the Muslim world for their external contacts. Equally, some of the savanna and forest peoples began to turn to the Christian newcomers in the south for their contacts with the outside world. However, many peoples in western Africa, and nearly all of those of central and eastern Africa, were entirely outside the direct influence of either Arabs or Europeans until 1800.

The purely passing effect of foreigners is well illustrated by the history of the East African coast. Here Arabs had established trading settlements at favorable harbors on the coast and nearby islands – for example, Mombasa and Zanzibar (Figure 3). These settlements were part of a large and prosperous Muslim trading system in the Indian Ocean, which at the end of the 15th century was taken over by the Portuguese. By the end of the 17th century the East African settlements had reverted to Muslim control. Neither the Arabs nor Portuguese in all this time had any contact or influence with any but the peoples actually living on the coast, except in the Rhodesia/Zambesia area where gold spurred inland expeditions.

|

| Kano in the north of Nigeria reached the height of its commercial power in the 18th century at the time of a Muslim revival. Usuman dan Fodio, leader of one of the principal Nigerian tribes, the Fulani, founded the Caliphate of Sokoto in 1807 and two years later took Kano. |

Human beings – "a most profitable trade"

When the Portuguese first arrived in West Africa, like European adventurers in the New World, they were interested in gold and luxury tropical products. But they and the Dutch, British, French and others who followed them quickly came to realize that there was only one profitable commodity in Africa – human beings (Figure 1). The lands of South and Central America, the Caribbean islands and the southern parts of North America required large labor forces to exploit the silver mines and, more important, the tropical crops – sugar, coffee and cotton – growing there. Within a few decades the transatlantic slave trade came to dominate relations between blacks and whites in western and central Africa.

From 1451, when the first cargo in this barbaric trade was shipped across the Atlantic, until the early 1870s, when the slave trade finally came to an end, it has been estimated that almost ten million Africans arrived in the Americas – one of the largest migrations of peoples in history. The peak of the trade was the 50 years from 1760 to 1810, by which time most of the European nations had abolished the slave trade; during these years, over four million Africans were taken away from their homelands. Most of the African slaves came from the inland regions – from Senegal right round the bulge of West Africa to the Angola region of west-central Africa. The African middlemen, who sold the slaves to the European "factories" on the coast (Figure 5), prospered from the trade, as did powerful raiding states such as Asante and Dahomey (Figure 6).

In the area of the Congo estuary and Angola, the Portuguese and their agents were more active in venturing inland in search of slaves. In the 19th century the East African slave-trading network, which up to then had been in Muslim hands, was tapped to supply slaves to Brazil and Cuba, where slavery persisted longest.

There is no doubt that the slave trade much increased the level of violence among many African peoples. This is especially true of the Niger delta region, neighboring areas of southern Nigeria, in the interior of Angola and, later in the period, in east-central Africa where Arabs controlled the trade. In a number of instances the resulting breakdown of social order led, ironically, to increased interference by the Europeans who were responsible for the violence in the first place.

Purely African cultures

During the 300 years from 1500 to 1800, in the areas of Africa unaffected by the transatlantic slave trade, societies were developing under their own momentum. New and powerful states emerged, such as Ruanda and Buganda (in the fertile lands between the great lakes of East Africa) and the states farther south, on the plateaus of central Africa. The kingdom of Monomatapa faced the Portuguese in the Zambezi valley and the Rozvi state dominated the plateau.