Themistocles (514–449 BC)

Figure 1. Themistocles.

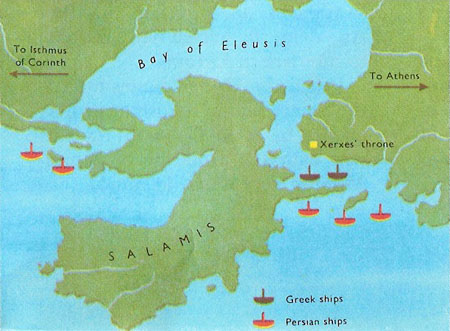

Figure 2. Battle of Salamis.

Figure 3. An ostrakon found in Athens. Clearly inscribed 'Themistocles Phrearrios' (his legal name). It may have been used at Themistocles's ostracism.

"The Athenians will defend their city with a wooden wall." So said the Delphic oracle in 480 BC, when Athens was threatened by Xerxes, King of Persia. But why a wooden wall?

Themistocles gave the answer. "By the wooden wall the god means our ships," he said; "it is by them that we shall conquer."

Events proved him right. Led by Themistocles and the Council of the Areopagus, the Athenians took to the sea and defeated the Persians at Salamis. This momentous decision was perhaps the highlight of the career of one of the greatest statesmen in Greek history.

Themistocles first came to power in 493 BC. He at once laid the foundation of Athenian naval strength by fortifying the Piraeus. Although out of sight of the Acropolis, the Piraeus was a much finer natural harbor than the unprotected open beach at Phaleron which the Athenians had used until then. Themistocles realized that Athens could become the strongest naval power in Greece. He also realized that Greece would need a powerful fleet when the expected clash came with the Persians.

The first blow was struck within three years. The Athenians defeated the Persians in 490 BC at the battle of Marathon, where Themistocles fought as a private soldier.

But Marathon was obviously only the prelude to a greater attack. While the Persians were making menacing preparations for this, a rich vein of silver was struck in the Athenian state-owned silver mines at Laurium. Some Athenians proposed that this wealth should be distributed among the citizens; but Themistocles persuaded them instead to use it to build 100 triremes (ships with thee banks of oars). These, he said, "would be useful in the war against the neighboring island of Aegina;" but they proved to be even more useful against the Persians.

Xerxes invades Greece

The Persian invasion came in 480 BC. Xerxes' total forces were said to be more than 5,000,000, though modern estimates are closer to 500,000. The Persian army was certainly too big to be shipped around the Aegean, and so had to march to Greece along the coasts of Thrace and Thessaly. It was also too big to live off the country for very long; its supply route by land was rocky and dangerous; it therefore had to be supplied by sea. So the Persian navy advanced along the coast, keeping pace with the army. But if the Greeks could decisively defeat the Persian fleet, the Persian army would be compelled to retreat.

In the face of their common danger, the Greek states made an alliance under the leadership of Sparta. After a gallant but unsuccessful attempt to hold the Persians at Thmermopylae and engage their fleet at Artemesium, the Greeks were forced to withdraw to the Isthmus of Corinth. This meant abandoning Athens; but Xerxes' army was to reach the Isthmus in safety, his fleet would have to defeat the Greek fleet anchored off the island of Salamis in the Bay of Eleusis.

The greek naval commander was a Spartan, Eurybiades; but thanks to Themistocles's foresight the Athenian contingent was by far the largest. Themistocles urged that here was the place to defeat the Persians; and when other Greeks were considering withdrawing to the Isthmus, he secretly sent Sicinnus, a trusted slave, to the Persian commander. "Tell him," he said, "the the Greeks intend to sail away during the night, and that Themistocles and the Athenians will desert to the Persians." The Persians fell into this trap. They sent a squadron of ships to block the western end of the island. Thus they ensured that the battle would take place at Salamis (Fig 2), just as Themistocles wanted. Next morning they advanced to attack the Greeks in the narrow waters between Salamis and the mainland. Themistocles had enticed them into the one place where their superior numbers would be of no advantage to them.

Xerxes watched the battle from a throne set up on Mount Aegaleos. Both sides fought bravely; but the Persians were defeated. Consequently their army had to withdraw from Greece. (They returned in smaller numbers the next year, but were finally defeated at Plataea.) Themistocles tried to persuade the Greeks to sail to sail at once to the Hellespont (Dardanelles) to cut off Xerxes' retreat into Asia. Being unsuccessful, he again sent Sicinnus to Xerxes, claiming that he had dissuaded the Greeks from attacking the Hellespont.

Rebuilding the walls of Athens

Alarmed at Athens' new naval power, Sparta wanted to prevent her rebuilding her walls. Themistocles at once went to reassure Sparta; other ambassadors were to follow. Meanwhile rebuilding began with all speed. First he told the Spartans that he had to await his colleagues arrival, then he suggested they sent envoys to see for themselves. These the Athenians held as hostages. When the walls were high enough to defend, the Athenian ambassadors arrived at Sparta, and Themistocles revealed the truth. To redeem their own envoys, the Spartans had to let Themistocles and his colleagues go free.

It then became known that he was implicated in anti-Spartan intrigues with the Persians. Sparta was then friendly with Athens and demanded his arrest. He made an exciting escape to Persia, where he successfully claimed Persian gratitude for his "services" to them in the Persian Wars! He ended his days in comfort as Persian governor of Magnesia, in Asia Minor.