triumph

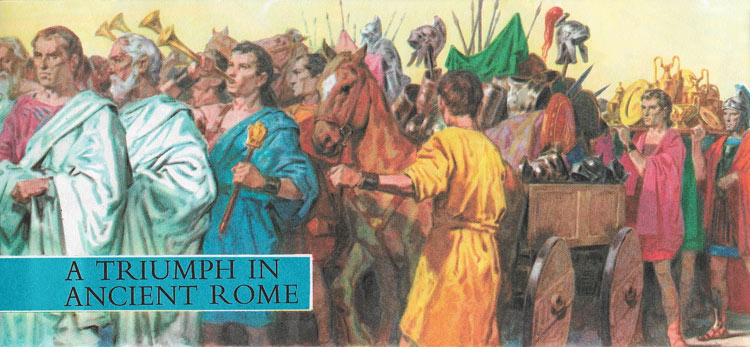

Figure 1. A triumphal procession headed by Senators advances along the Via Sacra through the crowd. The triumphantor rides in a golden chariot behind the lictors, and is followed by his most important prisoners and then by his legions.

Figure 2. Romulus, after his victory over Arco, hangs Arco's armor on a branch of oak.

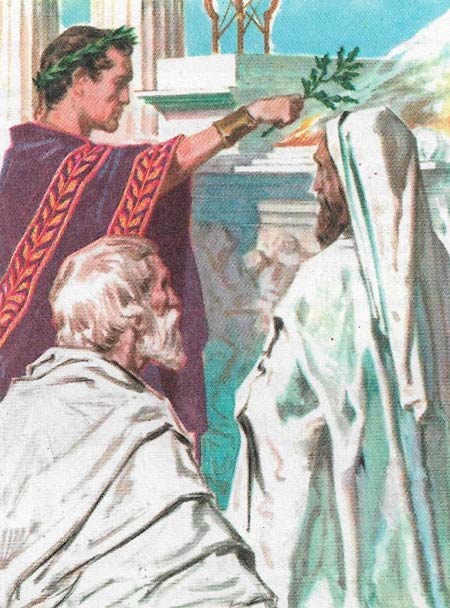

Figure 3. According to custom, the triumphator offers his laurel branch on the altar of Jupiter.

A triumph in ancient Rome was a public honor bestowed on a general who had been successful in war. It consisted of a solemn procession along the Via Sacra up to the Capitol, where sacrifice was offered to Jupiter (Figure 1). The victor stood in a chariot, drawn by four horses – his captives marching before, his troops following behind.

The ovation (from ovare, "to shout"), or lesser triumph, differed from the greater chiefly in these respects, that the imperator entered the city on foot, clad in the simple toga praetexta of a magistrate, instead of the toga picta and the tunica palmata of the more highly honored commander, that he bore no scepter, was not preceded by the senate and a flourish of trumpets, nor followed by his victorious troops, but only by the equites and the populace. The ovation was granted when the success, though considerable, did not fulfill the conditions specified for a triumph, or if the conqueror had not been in supreme command.

Origin of the triumph

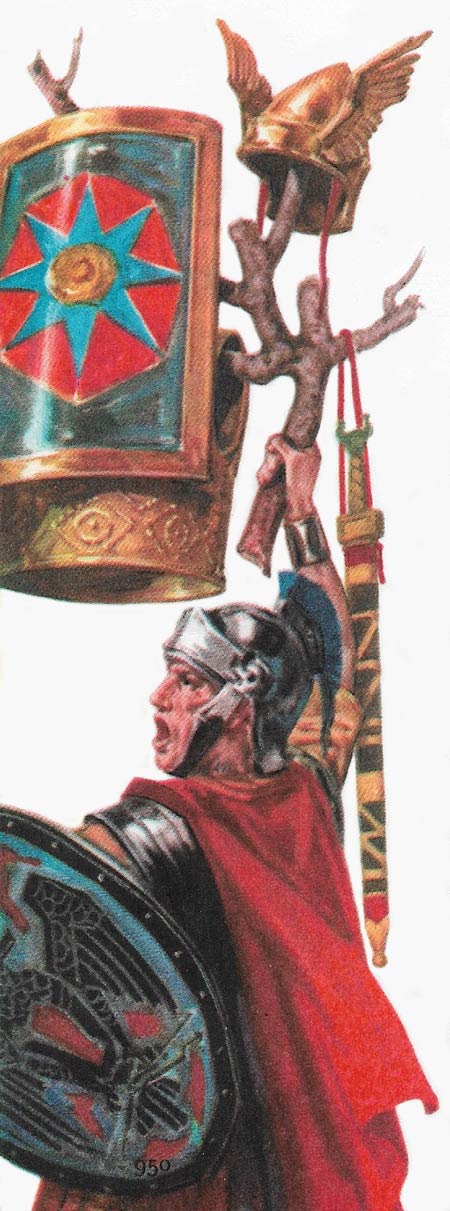

According to tradition, Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, was also a mighty warrior. In the wars in which he made Rome the leading city of Italy he was supposed to have killed many enemies in single combat. The most terrible of these duels was with Acro, the King of Cenina, which is one of the most ancient cities of central Italy. The duel between these two famous warriors was long and bitter, and for a time it looked as if Romulus would be defeated, but at last, with a clever stroke of his sword, he killed the unfortunate Acro (Fig 2).

Overjoyed by is victory over so mighty a foe, Romulus stripped Arco of his armor and, cutting a branch from an oak tree, he hung the armor from it to make a trophy. Then he placed a laurel wreath upon his own head and, holding the trophy aloft, marched back to Rome at the head of his soldiers, who sang a hymn of victory in his honor.

This sudden and unexpected action was most probably the origin of the strange Roman ceremony, known as a triumpus (triumph), which was both a religious and a military ceremony.

The right to a triumph

In the period when there were Kings of Rome, triumphs did take place, but we know little about them. In order to find out in detail how a triumph was celebrated, we have to refer to the Republican Age (about 250 years after the foundation of Rome).

In Republican and Imperial Rome a triumph was considered the highest honor that could be paid to a commander who had won a great victory. In order to establish his claim to a triumph, a Roman commander had to fulfil the following conditions:

1. To have been acclaimed as 'imperator' (commander) by his soldiers, who only gave their commander this honor in recognition of his great skill.

2. To have killed at least 5,000 of the enemy in a single battle.

3. To have led his troops into battle in person.

4. Not to have suffered any serious loss in his own army.

5. To have enlarged the territories of Rome by his victory. (The defeat of an invading army did not justify a triumph.)

A commander who felt that he had fulfilled all these conditions had to submit a written request for a triumph to the Senate, in which he detailed all his military successes. If the Senate decided that his claim was justified, they granted the commander a triumph and fixed a day for its celebration. Before the day, the commander was forbidden to enter within the pomerium (the boundaries of the city of Rome), but he was allowed to camp with his whole army in the Campus Martius, a large open space used for military training outside the city walls. If the Senate decided that the commander had not fulfilled all the conditions necessary for a triumph, he was awarded the lesser honor of an ovation. This meant that he went on foot through the main street of Rome, with a myrtle wreath on his head, while the crowd cheered him.

How a triumph was celebrated

On the day on which a great commander celebrated his triumph, enormous crowds gathered in the streets through which the triumphal procession was to pass. After meeting in the Campus Martius, the procession entered Rome through the Triumphal Gate. It reached the Via Sacra (Sacred Way) and passed on to the Forum to climb the Capitol, where it halted in front of the temple of Jupiter.

A party of Senators led the procession, followed by musicians playing military marches on trumpets and horns. Immediately behind came carts laden with the spoils of war; sometimes there were carts with tableaux (floats) representing some of the most important events of the war. Next came the sacred animals – the bulls with gilded horns – destined to be sacrificed to Jupiter on the Capitol. Behind them came the prisoners of war, their hands manacled with heavy chains. The lictors ( assistants to the magistrates), carrying garlanded fasces (bundles of rods with axe heads, to remind the people of the magistrates' power to flog and execute), came immediately in front of the triumphant general (triumphator). He stood in a golden leaves, with a wreath of laurel on his head and a branch of laurel in one hand. The enemy commanders and princes were chained to his chariot; in the last years of the Republic they were bound with chains of gold.

The ranks of the victorious legions closed the procession singing songs in honor of their commander. As the triumphator passed, the crowds hailed him with cries of 'Io Triumphe'.

When the procession reached the Capitol, the ceremony became much more religious. The commander offered the laurel branch and the garlands from the lictors' fasces to Jupiter (Fig 3). Then, surrounded by the temple priests, he sacrificed a white bull.

The ceremony ended with a banquet for the magistrates and senators; the soldiers were disbanded after getting their share of the booty.

Some curious facts

In the earliest years of the Republic, the triumphator's chariot was drawn by two horses, later by four, and in the time of the Emperor Augustus by six.

When, in 80 BC, Pompey celebrated a triumph for his great African victories, his chariot was drawn by four elephants, animals which represented the country where he had fought.

Triumphs were not always celebrated in Rome; occasionally they took place in the country where the commander had won his victories. Cornelius Scipio (later Africanus), for example, celebrated triumph in Spain, after conquering the Carthaginians there.

During the Imperial Age the Emperor was considered the commander-in-chief of the army; so when one of his generals had gained a great victory, the right to triumph was granted only to the Emperor.

A Roman historian of the 5th century AD tells us that 320 triumphs were celebrated in Rome between the time of Romulus (8th century BC) and the Emperor Vespasian (first century AD).

An impressive triumphal procession headed by Senators advances along the Via Sacra through the crowd. The triumphantor rides in a golden chariot behind the lictors, and is followed by his most important prisoners and then by his legions.