Wales to the Act of Union

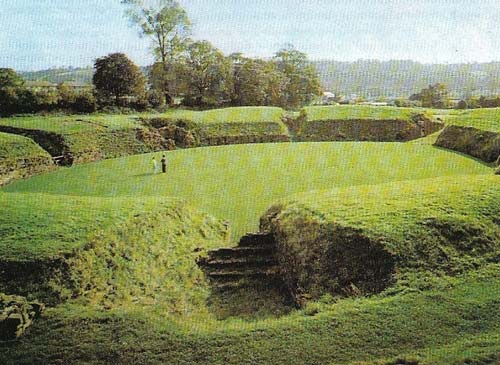

Figure 1. Caerleon-upon-Usk (Roman Isca) was, with Chester (Deva), the largest legionary base in or near Wales. The view shows the stone amphitheater at which soldiers of the 2nd Augustan legion might watch entertainments or military demonstrations. The amphitheater stands outside the fortress, built in AD 73.

Figure 2. This silver penny was minted by Hywel Dda, the first Welsh king to issue his own coinage. His coins, like this one, bore the words "Hopael Rex", or King Hywel, thus asserting his claim to rule all Wales and, by its Latin, demonstrating his civilizing intention. Hywel Dda earned his sobriquet "the Good" by codifying Welsh law;his system was to govern Welsh society until the imposition of English rule. He tried to organize Wales to conform with the rest of Christendom, and c. 930 had undertaken a pilgrimage to Rome.

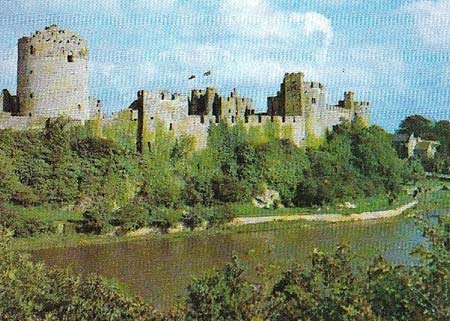

Figure 3. Pembroke Castle is typical of the Norman castles built in Wales. It was constructed originally as an earthwork motte, or mound, topped by a wooden tower, by Arnulf de Montgomery (fl. 1093–1102). In the revolt of 1094, when the Welsh were severely defeated by the Normans, it survived two sieges, and was almost the only castle in Wales not to fall. It subsequently became an important base for the reconquest of the country. It was rebuilt with a round keep of stone by the powerful William Marshall , 1st Early of Pembroke (d. 1219). Extended in the 13th century, it was much damaged in the English Civil War and greatly restored in the late 19th century.

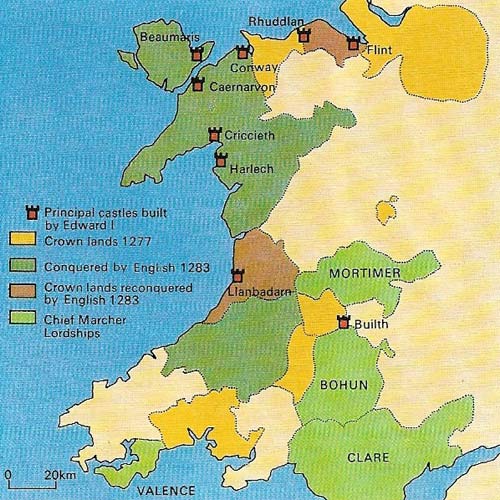

Figure 4. There was a new dispensation after the Edwardian conquest. The Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd was entirely dismembered and now became the shires of Anglesey, Merioneth and Caernarvonshire. With these, Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire. and Flint were held under the direct rule of the Crown, and these six shires were known as the Principality. The rest of the country, of which the possession had long been Norman, passing only occasionally into Welsh hands, was held as before by Marcher lords. The statute of Rhuddlan, enacted in 1284, provided the judicial and administrative framework by which the Principality was to be governed until 1536. But it made little difference to Welsh culture.

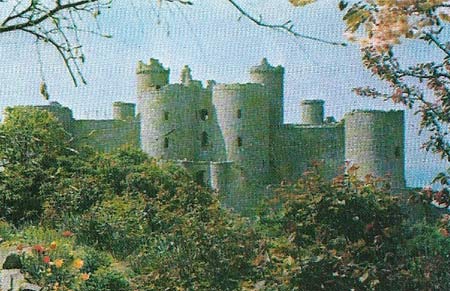

Figure 5. Harlech Castle was considered at the time to be the best fortified of all the powerful castles constructed by Edward I. It was built on a rocky site with a series of concentric defenses. Its mighty gatehouse was buttressed by several strong doors and portcullises, and it had no equal in Wales. The work, which cost over £8,000, was undertaken in 1283 by about 900 laborers, carpenters, and stonemasons, and completed within six years. The master mason was James of St George, who had gained his experience of castle-building in Savoy. His wage is recorded as three shillings a day, more than any other builder in the realm could command.

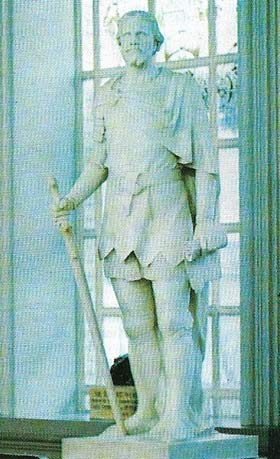

Figure 6. Henry Tudor was acclaimed in Wales as the first Welshman to be ensconced on the English throne. The bards jubilantly greeted Henry's triumph in late August 1485 as a victory for Wales and fulfilment of the hoary prophecy that a descendant of the Ancient Britons would oust the Saxon oppressors of their land. When he landed at Dale in Pembrokeshire with 2,000 Frenchmen in August 1485 and promised to deliver the Welsh from their "miserable servitudes", he did indeed attract a great many recruits. But although Henry rewarded his supporters and made some attempt to render the Welsh equal subjects with the English, he disappointed many expectations. In 1489 he revived the title of Prince of Wales for his young son Arthur.

Figure 7. The map shows the Welsh kingdoms in the 7th and 8th centuries AD. The largest of them, Gwynedd, was roughly the area that Cunedda had seized in the 5th century. It was to be the last outpost of Welsh independence. Powys was the kingdom next in importance and in the south Dyfed was sometimes united with Seisyllwg. The southeastern kingdoms were frailer, so that Rhodri the Great and Hywel Dda managed more easily to subdue them in their attempts to unite Wales in the 9th and 10th centuries. In the east the boundary of Wales was defined for all time by Offa's Dyke, constructed to mark the limits of the Kingdom of Mercia c. 790. Wat's Dyke was built to defend Mercia against Welsh raiders 80 or 90 years earlier.

The Welsh language and nation came into recognizable being with the expulsion of the Goidelic (Irish) Celts in the 5th century AD. The Welsh were slow to establish stable political and social order, but by the tenth century there had emerged uniquely Welsh institutions, codified by Hywel Dda or Hywel the Good (died 950) (Figure 2). Threatened by the Saxons, encroached upon by the Normans and finally conquered by Edward I, Welsh nationalism smouldered and flared, notably in the rebellion of Owain Glyn Thkr, or Owen Glendower (1359–1416).

The creation of a Welsh kingdom

Evidence from Goat's Hole at Paviland in Gower proves that Wales was inhabited in Paleolithic times by cave-dwelling hunters. After 8000 BC and until about 1000 BC Iberian migrants settled along the coast. Between 1000 and 500 BC the Celts penetrated Wales, bringing with them Druidism and the basis of the Welsh language.

The Celts remained the power in Wales until the arrival of the Romans in AD 43. Roman rule was largely military (Figure 1), and their chief interest lay in the Welsh mineral deposits, but they established a number of urban communities which exerted a civilizing influence. With the withdrawal of the Romans at the end of the fourth century, Wales was rent by the struggle for power between the Brythonic (native) Celts and incoming Goidelic (Irish) Celts. Largely through the efforts of Cunedda (flourished early fifth century), who founded a number of dynasties and the new kingdom of Gwynedd (Figure 7), the Irish were expelled. In the fifth and sixth centuries Christianity came to Wales, brought by such men as St Illtyd and St David.

|

| The tiny 4th-century chapel, here shown reconstructed, at Caerwent (Roman Venta Silurum)is the sole archeological evidence of Christianity in Roman Wales. Venta Silurum was a tribal capital situated in the better developed southeast, and it was in urban communities of this kind that Romano-British Christianity had modest popularity. |

Anglo-Saxon incursions during the seventh and eighth centuries greatly hindered attempts to achieve political unity in Wales. The limits of Saxon colonization of the Welsh borders are marked by Offa's Dyke, constructed in the mid-8th century. The reigns of Rhodri the Great (died 877) and Hywel Dda established a sound political and social framework, but the greatest measure of success was achieved by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn (died 1063) who fleetingly held sway over the whole of Wales.

Toward the end of the 11th century, Norman invaders seized control of large parts of Wales and consolidated their conquest with powerful castles (Figure 3) built at strategic points in the March of Wales (central and eastern Wales). But the princes of Gwynedd resisted their incursions and in the twelfth century presented a strong challenge to the English Crown. Llywelyn the Great (died 1240) began to weld the Welsh territories into a feudal state, and his grandson Llywelyn II ap Gruffydd (died 1282) was able to assume the title Prince of Wales and was recognized in it by Henry III of England in 1267. Henry's successor, Edward I, was less easily defied. He conquered Gwynedd in 1277, humbling Llywelyn and restricting his domain to west of Conway. Following Llywelyn's death in 1282 Welsh political independence came to an end.

|

| The head of the last independent Prince of Wales, Llywelyn II ap Gruffydd, King of Gwynedd, was borne through the streets of London after he was killed in a skirmish in 1282. Llywelyn was a first-rate soldier and a clever diplomat; he had behaved and been treated as a sovereign both by Henry III and Edward I. The revolt in which he died was not his doing, but he was bound to support it for reasons of kinship and pride. At his death "Wales was cast to the ground", as one chronicler wrote, and swiftly subdued. |

English rule and Welsh discontent

The Edwardian conquest destroyed the social system of five orders established by Hywel Dda. The brenin, or king, with the uchelwyr (nobles) and priodorion (freemen) had owned and ruled the land; subservient to them had been the taeog, serfs with some privileges, and the caethion, bondsmen with none. Kinship was the primary social tie, and because inheritances were divided between all the sons, smallholdings were the norm. Fast-moving social and economic changes after 1284 swept the traditional way of life away and produced a pattern of substantial landed estates and farms consolidated under a single ownership.

With these agrarian changes, and plague, slump and, not least, alien rule, there was discontent. From 1284 to 1536 Wales was divided into the English Principality (comprising the old Welsh kingdoms) and the Welsh March (Figure 4). In the Principality, English administration was harsh, Welsh law was disregarded, and commercial privileges were conferred mostly on English burgesses. There was at this time opposition throughout Britain to the Lancastrian regime, and, aggravated by local conditions, there were a number of rebellions in Wales, the most important being the Glyn Dwr revolt of 1400. Triggered by a dispute between Owain Glyn Dwr, Lord of Glyn Dyfrdwy and his neighbor Reginald Grey of Ruthin, the revolt soon spread nationally. Although it brought no political amelioration, the revolt stands high in Welsh national sentiment.

|

| Owain Glyn Dwr is a national Welsh hero (this statue stands in Cardiff City Hall), but ill-recorded as a man. His rebellion in 1400 drew enormous support from the peasantry but was mainly sustained by gentlemen and squires. Once he was established as a self-styled Prince of Wales, Glyn Dwr had the enterprise to form a constructive policy: he established an alliance with France, and proposed to create two universities and an episcopacy independent of Canterbury. He governed through the Welsh parliament he had summoned. When the tide turned against him after 1409, Glyn Dwr went in and out of hiding; he was active in 1415 for the last time. With this mysterious end, he was an inspiration to the bards who kept nationalism alive. |

Henry Tudor raises hopes

The collapse of the rebellion brought in its train penal laws reducing Welshmen to second-class citizens, but hostility to the English rule could find an outlet in the fifteenth century only in prophetic poetry. Prophetic bards assured Welshmen that a son of destiny would arrive to reassert Welsh supremacy in their land. During the Wars of the Roses the bards threw in their lot variously with the House of York or the House of Lancaster until, when the Lancastrian claim passed to Henry Tudor, they urged his support unanimously. Henry's victory at Bosworth in 1485 was hailed as a Welsh triumph. But the new king was an opportunist, and the call by the Welsh gentry for improved law and order and for equal rights with the English was not yet answered.